Is there any other basic repertoire opera so loved and yet so mistreated? It all goes back to the simple fact that Offenbach died, allegedly clasping the incomplete score to his breast, four months before the scheduled premiere in 1881. After that, chaos reigned and continues to do so.

The original orchestral parts – finished off by Ernest Guiraud, who also wrote sung recitative to replace spoken dialogue – were destroyed in a fire at the Opéra-Comique in 1887. New versions of the score interpolating music from other Offenbach works as well as that of other, sometimes unknown, composers were many throughout the mid-20th century.

My first performance of the work (the 1955 Met production, with Nicolai Gedda as the poet) was in a pretty much standard version for its time, which played the Giulietta scene as the second act and concluded with the revelry of the students in Luther’s tavern.

Off the top of my head, I can count 11 different productions of the opera that I’ve seen (some several times), of which all were in different versions. One kind theater went so far as to provide in the program a list of every number in the opera, its alternates, and sources (I just wish I could remember which theater that was so I could locate the program in the Leitmetzerin Sammlung, which seems to be doomed to a state of disarray until Camille makes good on her promise to put it all in order).

Despite there being no mention in the reviews published with the Met Archives, I seem to recall that the Otto Schenk production of 1982 conducted by Riccardo Chailly had a bunch of music I’d never heard before, including a rather sardonic habanera for Nicklausse in the first act, replacing the charming “Une poupée aux yeux d’émail,” which I never heard again until this Salzburg performance. If my memory has held up, somewhere in the run of the Schenk production, the acts were restored to Offenbach’s intended order (Olympia, then Antonia, then Giulietta).

It was really only after I moved to Europe that more allegedly complete, allegedly all-Offenbach versions began to appear, especially those by Michael Kaye and Jean-Christophe Keck. What you generally get these days is a hybrid of their work.

I have heard the opera with spoken dialogue replacing Giraud’s recitatives, with and without the spurious “Scintille, diamant,” the sextet (sometimes a septet) of unknown origin played in different acts or not at all, Giulietta dying from poison and Giulietta escaping with another lover, and the final number a reprise of the student’s raucous drinking song from the Prologue or the now commonly-played choral hymn led by the Muse, among other modifications. Stella sometimes merely appears, occasionally sings, or is totally absent. I’ve seen it with three (or four) female singers, and with one playing all three (or four) roles.

On more than one occasion, I contacted a press office to ask which version would be played, and was told, “We have our own special edition.”

Most recently, I was preparing for Stephan Herheim’s production at the 2015 Bregenzer Festspiele. My request to the press office was forwarded to several people within the Wiener Symphoniker organization until I finally received a reply that the Keck/Kaye edition as published by Boosey & Hawkes would be strictly adhered to.

No dice. Shortly after the opening bars, it became apparent that I was going to hear yet another mishmash, this one particularly egregious in that it splayed a great deal of music throughout the opera so that there was little left to play as the end approached, and many of the definitely non-Offenbach numbers once again intruded.

I rather like the edition used by Kent Nagano at Salzburg, although Waltraud Meier was apparently not up to the coloratura of the more interesting alternate aria for Giulietta, but at least she does get to sing an aria (not always the case). As noted the habanera is back, as is the moving final chorus.

While listening for the first time to Natalie Dessay’s totally insane interpolations in Olympia’s final moments, I was so astounded that I attempted to grab the knee of my guest, missed, and literally fell off the chair in my Grand Tier box, so while L’ubica Vargicová gives a terrific performance, I can’t imagine anyone will ever wipe out that memory (can you say liu-bitz-ah var-gitz-co-va?).

The standout performance for me is the luscious, heartbreaking Antonia of Krassimira Stoyanova, capped with a perfect sustained trill; she remains at the top of my list of lirico-spintos for at least the past decade.

Whatever the version, I adore Hoffmann and, just like the Mozart Requiem, I guess we’ll just have to consign ourselves to the fact that we’ll never know what we were truly meant to hear.

Jacques Offenbach: Les contes d’Hoffmann

Konzertvereinigung Wiener Staatsopernchor

Wiener Philharmoniker

Kent Nagano, conductor

Großes Festspielhaus

Salzburger Festspiele

30 July 2003

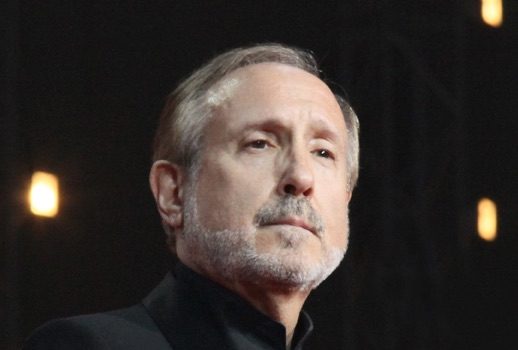

Hoffmann – Neil Shicoff

Olympia – ?ubica Vargicová

Antonia – Krassimira Stoyanova

Giulietta – Waltraud Meier

Stella – Ursula Pfitzner

Lindorf – Ruggero Raimondi

Coppélius – Ruggero Raimondi

Le docteur Miracle – Ruggero Raimondi

Le capitaine Dapertutto – Ruggero Raimondi

La Muse – Angelika Kirchschlager

Nicklausse – Angelika Kirchschlager

Andrès – Jeffrey Francis

Cochenille – Jeffrey Francis

Frantz – Jeffrey Francis

Pittichinaccio – Jeffrey Francis

Nathanaël – John Nuzzo

Hermann – Markus Eiche

Maître Luther – Peter Loehle

Spalanzani – Robert Tear

Crespel – Kurt Rydl

La voix de la mère d’Antonia – Marjana Lipovšek

Schlémil – Jochen Schmeckenbecher