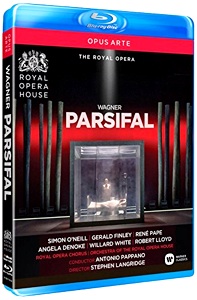

Contemporary stagings of Parsifal tend to be spare, abstract affairs scrubbed of religious associations, knights in armor and, sometimes, a grail. Modern dress, stylized gestures and suggestive symbols are supposed to help audiences navigate Wagner’s mystifying tale of redemption. Stephen Langridge’s 2013 take for Royal Opera, now available on Opus Arte

, is an especially grim, heavy handed specimen that doesn’t show a great deal of confidence in the music or the audience. There’s misery at nearly every turn, with the music functioning for long stretches as accompaniment to an almost cinematic treatment of suffering and fear. While some of the imagery may be riveting, there is little sense of the hero’s spiritual development, or what makes the Grail brotherhood tick.

In his director’s note, Langridge notes the need to overcome the opera’s narrative traps: Parsifal needs to find the beginning of his story to make sense of the present while Kundry searches for a coda to give her life story meaning. He’s also taken by the way the Grail knights interact with Amfortas like relatives pre-grieving a loved one on the brink of death, incapable of letting him go. The community is secretive, vaguely militaristic and desperate.

Langridge and designer Alison Chitty, who collaborated on ROH’s 2008 staging of Harrison Birtwistle’s Minotaur, set much of the action in and around a large cube, by turns transparent and opaque, that functions as Amfortas’ hospital room and a setting for pantomimes illustrating the opera’s backstories. The scenes of Klingsor taking a knife to himself, Parsifal scaling the walls of the magician’s castle and Kundry seducing Amfortas come off as gratuitous and divert attention from the opera’s surging energy. Even more questionable is the decision to send Kundry and Amfortas off hand-in-hand at the end of Act 3—a particularly awkward attempt to tie a bow on the characters’ struggles with their pasts.

With such tangled stage business, it’s left to René Pape, Gerald Finley and Angela Denoke to carry the day vocally. Denoke is a highly expressive Kundry, more repentant than seductive, who carefully marshals her big lyric soprano through the long evening and only sounds overtaxed at the end of Act Two, when the tone spreads uncomfortably. Her almost gleeful laughter as Parsifal defeats Klingsor’s guards and the reckless way she tackles the nearly two-octave dive on the word “lachte,” describing how she scorned Christ on the cross, add a welcome unhinged quality to highly charged scenes.

Finley continues to display impressive Wagner chops following his 2011 Hans Sachs at Glyndeboune, turning in a passionate, remarkably tender portrayal of Amfortas. Beyond spending a lot of time on a drip in the hospital bed, he is front and center in the production’s most disturbing scene, the Act One celebration of the Eucharist, which he turns into a very literal ritual by piercing the side of a young boy in a loincloth whose blood is then passed about.Pape is spared such directorial excesses and spends a lot of time standing around in a business suit confirming his status as today’s preeminent Gurnemanz. His bel canto sensibilities and coloring of vowels are especially vivid in the final act. Willard White is a formidable Klingsor, while Robert Lloyd deploys a still-effective bass singing Titurel onstage from a wheelchair in Act 1.

In the title role, Simon O’Neill’s tenor sounds pinched and a bit caustic in the outer acts but rings out convincingly during the pivotal Act 2 scene with Kundry, when he suddenly experiences the suffering of Amfortas, bellows “Die Wunde!” and rolls out of bed. Bearded and thick of build, O’Neill looks more like building security than an innocent youth and doesn’t lend much dramatic presence, even after he’s blinded by the spear-wielding Klingsor.

Antonio Pappano leads an uneven performance in the pit, extracting some lovely detailed orchestral effects during the middle act but failing to quite capture the grandeur of the transformation scenes or maintain enough narrative continuity during the 1:50 first act. The orchestra plays authoritatively, and the chorus is equal to the task, if a bit distant on the DVD. Extra features include interviews with Pappano and O’Neill and Finley singing excerpts to a piano accompaniment.

Though the production represents ROH’s contribution to the Wagner bicentennial, it pales next to recent releases such as François Girard’s deeper, Buddhism-tinged production from the same year for the Met. Directors may be wise to avoid traditional Christian readings of this opera, but the evidence shows it’s easy to stray too far in an effort to reconceive the action.