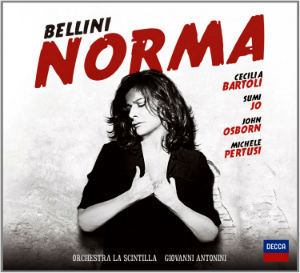

For better or worse, Decca’s new Norma recording

will ultimately be embraced—or dismissed—by those reacting directly to Cecilia Bartoli’s controversial portrayal. After all, few operatic roles prove as irresistible yet as fraught with obstacles to the modern diva as Bellini’s Norma.

In recent decades such bel canto specialists as Gwyneth Jones (with Jane Henschel as Adalgisa and a young Jonas Kaufmann as Flavio), Anna Tomowa-Sintow (with Denyce Graves as her Adalgisa), Maria Guleghina, and Carol Neblett have tackled the Druid priestess with decidedly mixed results.

However this important recording proves to be much more than a diva vehicle: a flawed yet endlessly fascinating effort to apply historically-informed performance (HIP) practices to this beloved early 19th century opera.

In his essentialBased on a new critical edition prepared by Maurizio Biondi and Riccardo Minasi, this new Norma CD should prove an ear-opening revelation to those able to set aside years of familiarity with recordings (both studio and live) of Bellini’s miraculous score usually disfigured by hundreds of tiny snips, tweaks, and transpositions, some of the most familiar attributed to one important interventionist Gossett spends an entire chapter dissecting: Tullio Serafin.

While performances and recordings of 17th and 18th century operas have been tackling the challenge of “authenticity” for years, it’s been far less common in the 19th century repertoire, although there have been numerous interesting attempts before Norma, mostly on recordings.

Jesús López-Cobos’s recording of Lucia di Lammermoor from the mid-1970s with Montserrat Caballé and José Carreras marked an important step in returning to Donizetti’s original conception. Sir Charles Mackerras went even farther on his Lucia recording

using The Hanover Band, an original instrument orchestra.

But it was not the first bel canto recording to do so: with Capella Coloniensis (founded in 1954 as the first orchestra to embrace new research into period performance practices), Gabriele Ferro earlier recorded three Rossini operas, La Cenerentola and L’Italiana in Algeri

, both with Lucia Valentini-Terrani, and Tancredi with Fiorenza Cossotto (now out-of-print).

Marc Minkowski’s L’Inganno felice is a particularly fizzy Rossini recording done with period forces, but Minkowski and his Les Musiciens du Louvre have also embraced Offenbach, doing witty versions of La Belle Hélène

and La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein

, both with Dame Felicity Lott, on stage and on CD.

Minkowski continues his HIP exploration of the 19th century next week with an intriguing double bill at the Opéra Royal at Versailles: Pierre-Louis Dietsch’s 1842 Le Vaisseau fantôme ou Le Maudit des mers (with Sonya Yoncheva), followed by Wagner’s Der Fliegende Höllander (starring Evgeny Nikitin as the Dutchman) which premiered the following year.

A master of Bach, Handel and Rameau, John Eliot Gardiner has also frequently turned his attention to 19th century French music. His conducting of Berlioz’s Les Troyens, which I was lucky enough to hear in Paris ten years ago was a revelation: the ravishing colors and sonorities of the period instruments made the work sound brand-new.

His comique version of Bizet’s Carmen with Anna Caterina Antonacci and Andrew Richards is similarly fascinating. With his Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique, Gardiner has even dipped into 20th century opera in a 2010 production of Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande.

A few baby steps have also been taken in German opera: before Minkowski’s imminent revival, Bruno Weil had recorded Wagner’s Der Fliegende Höllander, along with Weber’s Der Freischütz (out-of-print) both again with Capella Coloniensis, while Sir Simon Rattle first dipped his toe into Wagner’s Ring with a concert performance of Das Rheingold with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment.

Rapturously mentioned by Zachary Woolfe in The New York Times earlier this year, Parsifal with Thomas Hengelbrock and his Balthasar-Neumann-Ensemble (the conductor and orchestra with whom Bartoli sang her first Norma in concert in Dortmund in 2010) will be broadcast by several German radio stations later this month. In addition to using period instruments, many of these recordings and performances also took advantage of new, corrected scores.However, Decca’s is not the first recorded Norma using original instruments. With his stellar orchestra Europa Galante, Fabio Biondi conducted an early version of the new critical edition in Parma in 2001.

Gossett is particularly pithy discussing this production: while applauding many of Biondi’s orchestral felicities, he deplores the reluctance of the singers to similarly rethink their approach to the music—June Anderson and Daniela Barcellona simply performed the same Norma and Adalgisa they would have done with any other conductor or orchestra.

I have never been able to listen to Anderson without wincing, so I was unable to get through much of this performance; however, there is a later broadcast with Biondi conducting another Norma—the unknown (to me) soprano Katia Pellegrino—and it’s an exciting rendition.

The most unusual aspect of Biondi’s performances is his use of a continuo fortepiano throughout—often the composer would sit in the pit “at the cembalo” but there seems to be little evidence that the instrument was necessarily played, particularly in this opera without any secco recitative. It’s interesting to hear the pianoforte during Bellini’s music, but I agree with Gossett that it sounds quite wrong.

Decca’s Norma conductor Giovanni Antonini’s rhythmically vivid direction exploits the skill of his superb orchestra La Scintilla (the period group in residence at the Zurich Opera) to bring out many unexpected colors and contrasts in Bellini’s orchestration. A relative newcomer to bel canto and originally a recorder and traverse flute virtuoso and founder of Il Giardino Armonico, Antonini proves more at home than did his predecessor on Bartoli’s earlier (and less successful) Bellini recording, La Sonnambula.

The mellow traverse flute solo of “Casta diva” is particularly arresting, as are the more pungent gut strings and natural horns, trumpets and trombones. Unfortunately Decca’s libretto lists neither the musicians nor the members of the chorus so it’s impossible to know the size of the forces used.

Sadly, decades of sterling performance both on stage and on recordings by advocates of HIP have done little to prevent embarrassingly out-of-date complaints about scratchy violins or out-of-tune horns that continue to be held by those either trapped in their allegiance to only things familiar or just plain ignorant about this movement of music-making over the past 40 years.

One needs only to hear the fervent overture played with fire and flair by La Scintilla to discover that this intimate, heartfelt Norma may prove a most worthwhile journey in rediscovering an opera one already thought one knew well.

And what a joy to hear the score uncut—it’s remarkable just how many passages are nearly always dropped or changed; the great trio that concludes Act I proves particularly interesting in its much fuller unabridged form. We get both verses of the cabalettas to Pollione’s and Norma’s arias with the repeats strikingly ornamented, as are numerous passages in both Norma-Adalgisa duets.

Despite its completeness, the total timing (on just 2 CDs) is shorter than many “butchered” performances/recordings due to the often surprisingly brisk tempi. The notes in the CD booklet about the critical edition argue that these faster speeds reflect tempo markings in Bellini’s autograph score.

For example, the first Norma-Adalgisa duet pulses with the excitement of two women sharing their experiences of a forbidden seduction rather than meandering with a languorous tempo more suitable to a love duet. A frantically quick “Guerra” chorus is tremendously threatening; its barbarism highlighted by the vibrant singing of the previously unknown chorus, The International Chamber Vocalists.

The most conventional portrayal of the four principals is bass-baritone Michele Pertusi’s Oroveso. He does what he can to enliven a basically uninteresting character, but I find his voice rather light for the Druid leader lacking the gravitas and sonorous low notes one ideally wants.

The Roman consul Pollione has always been the biggest obstacle to my completely capitulating to this opera—his last-minute transformation always strikes me as unbelievable given his heretofore recklessly predatory behavior toward both Norma and Adalgisa. His challenging scena also is uninspired and ungrateful to the tenor.

Decca’s Pollione, American John Osborn (best known for his Rossini roles, including recently Arnold in Guillaume Tell) performs the role created by Domenico Donzelli, the first Torvaldo in Rossini’s Torvaldo e Dorliska and the first Belfiore in Il Viaggio a Reims.

His casting is remarkable since one more usually encounters brawny lesser-known Verdi/Puccini tenors in the role. Despite the occasional more nuanced Franco Corelli or Carlo Bergonzi, one more likely hears instead Robleto Merolla, Francisco Ortiz, Adriaan vam Limpt or Amadeo Zambon.

Osborn’s voice usually strikes me as unattractive and his hectic, pressured first-act scene with particularly screamy high notes in the repeat of the cabaletta only confirmed my previous disdain. However, he eventually does achieve a minor miracle: transforming Pollione into a fascinating character, a compulsive seducer, sure of his allure and not eager to let go of the women he’s conquered. Osborn’s aggressive seduction of Adalgisa is a frightening manipulation, displaying a brutal ego in overdrive. He does try without much success to make his “conversion” in the final moments convincing.

Rather than the usual preference for a an off-duty Azucena or Amneris, casting a soprano as Adalgisa (recalling the role’s creator Giulia Grisi—who later sang the title role as well) remains far from common but it’s not unprecedented. Although a fiftyish Caballé recorded the role for the second Joan Sutherland version, she was probably few people’s ideal innocent virgin.

However, Patricia Brooks, Margherita Rinaldi, Eva Mei, Lella Cuberli and a young Antonacci have done the role more successfully—Nancy Tatum, not so much. Mariella Devia’s recent first assumption of the title role also paired her with a soprano Adalgisa, Carmela Remigio. After Caballé, the most illustrious soprano to try a bit of Adalgisa is Mirella Freni in the second act duet with Renata Scotto.

Even so, the choice of Korean coloratura Sumi Jo as Adalgisa was a surprise. I must admit that the soprano hasn’t really been much on my radar—I’ve only heard her once in person as Oscar at the Met over 20 years ago and her recordings have mostly escaped my notice; however, her sweet fragile Adalgisa is rather touching. While older than Bartoli, she sings with a girlish freshness which is remarkably different from some other soprano Adalgisas.Surprisingly her coloratura is rather choppy (perhaps to match her partner’s?). And there is a clear avoidance of long loud high notes—everything is touched then gotten off quickly. Her fearful capitulation to Pollione as he intently breaks her down in their duet concluding the first scene is shockingly convincing, as is her devastation at his appearance at Norma’s home.

The announcement several years ago that Bartoli was planning to do Norma in concert was characteristically met with both eager anticipation and dismissive derision. What on earth was a small-voiced baroque and Rossini mezzo doing tackling a role so closely identified with some of the grandest sopranos of the postwar era: Caballé, Sutherland and, most of all, Maria Callas?

Those two concert performances led to sessions for this recording which spanned April 2011 to January 2013, while her first fully staged Norma (again with Antonini, Osborn and Pertusi) arrives on May 17 at the 1500-seat Haus für Mozart during the Salzburg Pfingsten Festival of which she is the artistic director. Further performances will follow during the summer festival there.

Bartoli argues in an extended essay accompanying the CD that her research into the life and career of Maria Malibran for her Maria recording led her to believe that some bel canto works usually thought of as high soprano vehicles were really conceived for women who today would likely be called mezzo sopranos, particularly Malibran and Giuditta Pasta, Bellini’s first Norma and Amina in La Sonnambula.

Adjusting the tuning down to what something close to what would have been the norm in the 1830s—A=430 for this recording—reinforces Bartoli’s claims. She also argues that the darker color of a mezzo contrasts more effectively with the soprano intended by Bellini for Adalgisa.

Surely we have all heard (or heard of) sopranos whose repertoire more commonly consists of verismo operas or late Verdi performing Norma without the necessary agility or bel canto nuance required by Bellini. Though they surely have their fans, one wonders what the composer might have thought of the portrayals of, say, Gina Cigna, Zinka Milanov or Ghena Dimitrova?

Even the great Lilli Lehmann who introduced in 1890 Norma to the MET where she had debuted as Carmen and was by then also a famed Brünnhilde was criticized by W. J. Henderson in The New York Times at that first performance for her lack of stylistic refinement:

It must be said, however, that Frau Lehmann took many of the elaborate ornamental passages at a very moderate tempo and sang them with very evident labor, thus depriving them of much of that brilliancy which the smooth, mellow, pliable Italian voices impart to them. Fiorituri without brilliancy have no “raison d’étre,” and no Italian diva of standing would have received half the applause that Frau Lehmann did for singing these passages as she did. The audience was excited by astonishment at the fact that she could do it at all.

Initially skeptical that Bartoli had any business singing this role, I came away with a mixture of admiration and disappointment. It’s clear throughout that she has thought deeply about Norma and her command of many of its difficulties is impressive.

It’s a joy to hear a native Italian sing Norma (she is one of few in the postwar era—among the others, Scotto, Anita Cerquetti, and Fiorenza Cedolins). However, one can hear Bartoli attempting to use her vivid declamation of the text to compensate for moments when she is overpowered vocally, and, too often, her very dramatically rolled r’s go way over the top.

For those who have followed her career over the past two-and-a-half decades, much of the singing will not be a surprise: the rich mellow middle voice remains steady and eloquent, while ascents to the top become small and breathy—those high C’s at the climax of “Oh non tremare” lack the required visceral sting. However, the long legato lines of “Casta diva” or “Teneri figli” are floated eloquently on an apparently endless supply of breath.

Sadly the “Gatling gun” coloratura that has plagued much of her singing for the past decade has only gotten worse, more detached and mechanical. Apparently it doesn’t bother much of her audience as I’ve attended concerts where reams of these pecked-at notes are greeted with ecstatic cheers. For me, it remains the least attractive aspect of her singing but then I’ve always felt her to be most accomplished at adagio rather than allegro.

The more intimate scenes unsurprisingly shine whereas the more dramatic, public ones often fall short: her cries for war sound puny while the two scenes with Adalgisa reveal a hushed intimacy that is truly moving. The final scene poses the biggest challenges and exposes some of Bartoli’s weakest moments; in particular the “In mia man” duet with Pollione lacks the ideal ferocity and those wonderful rising trills on “Adalgisa fia punita; nelle fiamme perirà” don’t sound at all.

However, her “Qual cor tradisti” (where Osborn is finally able to suppress the “bray” in this tone) and her pleading “Deh non volerli vittime” are lovingly spun on an aching thread of silvery tone that proves most moving, particularly as the intense chorus cries implacably for her death.

That Bartoli feels the need to similarly plead with the audiences of the world for her right to sing Norma is disturbing. Artists should take risks and challenge themselves, and throughout her career Bartoli has never embraced the obvious path. I also suspect that no amount of historical argument about Pasta or Bellini will convince those who will choose to perceive this project as a huge act of hubris.

However, since there can never be a truly definitive interpretation of this (or any) great role (not Callas with Serafin, not Caballé at Orange, not Sutherland with Marilyn Horne), it remains important for artists such as Bartoli to continue to offer up their talents and insights to help keep Norma a living work—rather than something that we don’t need to re-examine as it was already done “right” decades ago!

All in all, Bartoli’s portrayal is a surprising, uneven, yet impressive achievement. In many ways I prefer her to her contemporaries like Edita Gruberová whose hard-edged, impossibly un-Italianate manner always seems so wrong for bel canto. Devia’s uneven recent assumption of the role (performed near her 65th birthday) has many fascinating qualities but one is frequently saddened by her having waited so late to take it on.

Unlike many, I find Angela Meade an appealing artist and look forward to her upcoming Met performances (a friend attended her recent Norma in DC and ventured that she had improved immeasurably from her first attempts at Caramoor) with the promising Jamie Barton as Adalgisa and who can resist Meade’s high D at the end of the trio?

One wonders how co-editor of the new critical edition Minasi will feel about the Met’s presumably musicologically unenlightened production this fall when his wife Kate Aldrich performs Adalgisa opposite Sondra Radvanovsky, whose Norma I await with hopeful trepidation.Meanwhile Bartoli continues explore new roles: next season brings her first Alcina in a new production of Handel’s opera in Zurich, along with a surprising return to her Rossini mezzo roots with her first Isabella in L’Italiana in Algeri, with Jean-Christophe Spinosi conducting his period group Ensemble Matheus.