An aged Giacomo Casanova, forgotten and bored with life’s prospects, has decided to kill himself. This man, who has always lived according to the liberties of his chemical attractions, allowed himself to be ruled by Nature, now at the end attempts to assert control. But Nature, too crafty to be denied, holds him back from the edge; a stroke fells him before he can drink his poison.

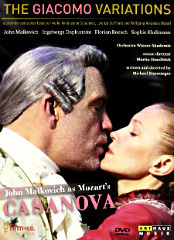

During his recuperation, the poet Elisa van der Recke arrives seeking to publish his memoirs. Intrigued, he woos her with a glimpse into his exploits. He opens his past to her in the hope she will open to him. His famous life is a series of seductions; in each, he explains, he played a different role, a different side of himself: “There is the Giacomo theme and then there are its variations, such as: the priest, the spy, the gambler, detainee, the escapee, escapist, the analyst, the anal-ist, the alchemist…” Michael Sturminger‘s The Giacomo Variations follows this voyage as the four-actor company takes on, in turns, the mantle of these memory-Casanovas, embodying the variations adopted in the pursuit of Nature’s passions.

Drawing upon the historical Casanova’s connection, as correspondent and sometimes friend, to Lorenzo da Ponte, the The Giacomo Variations is a hybrid of play and opera, blending music from the Mozart/da Ponte works into a memoir of Casanova’s multifarious experience. The mix is an uneasy one, rarely able to completely bridge the two worlds.

In this production, filmed in Vienna, John Malkovich’s Casanova is the prime example of this disjunction. His portrait is nuanced and commanding, charismatic with a hint of lingering danger beneath a worn exterior, and suddenly revived when reaching into the past. But he flounders musically, managing to sound something like a sick Rex Harrison when solo and completely at a loss when forced to join in ensembles.

Lithuanian actress Ingeborga Dapk?nait? fares better as van der Recke, wary of Casanova’s rakish side, but drawn to him as she idealistically searches for some hidden heart. Her acting holds its own alongside Malkovich and her voice is confident and pleasant, if thin.

Mozart veteran Florian Boesch (the strongest singer, though occasionally crossing into hamminess), and German soprano Sophie Klußmann (a clear, light voice but larger and more generalized in her acting than the others) fill out the cast, trading off, along with Dapk?nait?, a range of the roles in Casanova’s memory. The supporting players are hindered, however, by this carousel of personalities; they move so frequently from one to the next that only Malkovich’s Casanova is able to establish a solid impression, the rest merely shadows flickering in his orbit.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bLQMRvxr8lA

The greater problem emerges in the structure of the play. As we delve into Casanova’s tales, it becomes a picaresque series of adventures, one unusual conquest after another: an eighteenth-century Victor/Victoria as a castrato is revealed to be soprano in disguise, the charming of two nuns at once, the accident of nearly marrying his unknown daughter by a former conquest.

The stories are interesting enough in themselves, illustrating the range of his passions and the relentless of his pursuit, but, lacking the necessity of any particular moment, a feeling of repetition quickly sets in. Any one could be fleshed out into a full drama of its own, but racing by they are insubstantially brief. It is the same difficulty that befalls Candide; our hero travels from one adventure to the next, dramatically treading water for half the evening, until a dramatic moment is tacked on at the end.

Casanova’s seduction of Elisa van der Recke provides the active drama. His past has been marked by forceful conquests, whether outright rape or the subtle stripping of defenses. Initially he approaches her as any other woman, strategically attempting to break away her barriers. Near the play’s end, as he draws to the close of his memoirs, his find the hunger of pursuit has crossed into affection. Of course, inexorable Nature has one last trick up her sleeve, the fatal blow before this uncharacteristically tender passion can be consummated.

As ironic death denies Casanova his changed nature, so the selections from Mozart’s operas cannot retain their vitality when repurposed. An accompanying note by music director Martin Haselböck claims the link between Casanova and Mozart/da Ponte to be the expansive knowledge of human nature the former gained in his conquests and the perceptiveness of the latter capturing it musically.

But the fascination is lost when the music is stripped of its specifics. A few clever moments succeed; the revelation of the daughter-bride occurs with a leap into a parallel moment of Figaro. But the musical digressions are usually obvious (Casanova first discusses his memoirs and we are interrupted for Don Giovanni’s catalogue aria) or bland (a lover learns that Casanova has forgotten their long-ago relationship; her pain is voiced as the soprano emerges to embrace her with “Porgi, amor”).

The music is primarily introduced extra-diegetically, functioning as outside commentary to the scenes. Within their respective operas, the Mozart/da Ponte arias respond to specific dramatic contexts. Here, relating only to the general mood or theme of a scene, they are deprived of that agency and become generalities.

“Porgi, amor,” for instance, is admittedly vague in its text. But within Figaro it is the lament of the Countess arising out of emotions driven by a sequence of events. Here, coming to us second-hand and voiced by an unidentified third party, the emotion, at which the preceding scene has already arrived, is all that remains. The aria becomes an extension of a moment, rather than the moment.

In the end, the insertion of the music is unable to offer any deeper substance than the play provides, so the whole affair becomes as spent as the weary Casanova who opened it.