Happily, this Rheingold, which returned to the Kennedy Center Saturday night to open the first of three complete cycles, has been shorn of its clumsier gestures. What’s left is a taut, character-driven production that wields its referential material with care, giving us a manageable set of core images that keep the dramatic and intellectual machinery of Das Rheingold buzzing. While Zambello’s productions can be hit or miss (I’m still smarting over that Ariadne at Glimmerglass two years ago) she is surely in her element here, presiding over a cohesive, well-constructed drama tinged with playful irreverence.

The key device of this production, as anyone with Internet access has probably gathered by now, is a vaguely gilded age/Gatsby-ish treatment for Wotan and his crew. That’s a reasonable enough place to plop the Ring gods in American history, but the 30,000 foot reading isn’t the interesting thing here. Rather, it’s how Zambello scours that basic idea for illuminating dramatic tidbits that help to tell a richer story about the characters.

The world of early 20th century idle rich exuberance nicely telegraphs the deities’ anxious mix of desperation and entitlement, their elegance a thin veil separating them from Alberich’s grubby climbing in the zero-sum political economy of the Ring’s fantasy world. That pervading air of entitlement also raises the stakes for the gods’ clash with workmen Fasolt and Fafner, adding an easily recognizable element of class contempt to Wotan’s willingness to cheat the giants. Prep school jerks Donner and Froh aren’t just motivated by protecting Freia’s honor; their disdain for the giants is wrapped up in their need to disguise protecting their status with the defense of noble virtues. And so on.

The tighter focus in this iteration is also evident in what got left out when the production was revisited for its presentation in San Francisco in 2011. Fraught symbols that added little to an understanding of the drama have been wisely revised, from small heavy-handed details (the rhinegold itself is now merely pretty sheet of gold lamé instead of a gilded homespun quilt) to major distractions (Erda’s ill-advised full-bore “American Indian” getup has been throttled back to something neutral from Anthropologie’s summer clearance rack).

Even the famous Old West Rheingold opening, which I’ve enjoyed snarking about for a decade, is subtly effective now. Alberich is still a prospector—again, not terribly interesting for any novel insights about American history. But in the less cluttered telling this choice becomes more interesting for what it insinuates about Alberich’s character—far from a base, idle dwarf, the prospector figure denotes grit and perseverance, a harbinger of the challenge he will eventually pose to Wotan.

WNO has fielded a strong ensemble for this cycle, featuring many familiar faces from the original productions. Alan Held’s intimidating baritone is an ideal vehicle for his maniacally confident Wotan, easily cutting through the orchestra with vivid attention to the text. While his has never been the prettiest sound, and we’ll see how he fares in the more lyrical demands of Die Walküre, this is a profoundly satisfying marriage of voice and character. Wotan’s great moment of disillusionment after he relinquishes the ring is shattering in Held’s portrayal—an agonizing first brush with self-doubt for the cocky deity.

Elizabeth Bishop, also a return player, easily charms the audience as exasperated matron Fricka, gamely shouldering much of the comedy that Zambello wrings from the hectic family scenes. Though clear and authoritative, her mezzo sounded perhaps a bit thinner relative to previous hearings.

Froh and Donner make the most of their turns as spoiled sons of the elite, though neither makes the vocal impact sometimes possible in these roles (speaking of, see Held’s totally 80s Donner in the Schenk video). Melody Moore rounds out the clan, settling into a warm, womanly sound for Freia. Moore has a unique assignment in this production—Freia returns from her time in Riesenheim having fallen for captor Fasolt, and must genuinely mourn his murder by Fafner. I’m not totally sold on this, though the rich-girl-gone-bad trope works in the context of the production and Moore played it effectively despite very little text to work with.

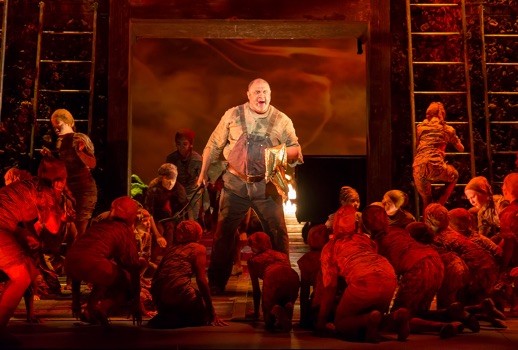

Gordon Hawkins is back from the initial run as well, his towering portrayal of Alberich every bit Das Rheingold’s shriveled heart. His resonant, slightly acidic bass-baritone serves as a terrifying vehicle for Alberich’s resentful conviction, though, while always committed dramatically, he doesn’t quite achieve that level of additional vocal interest needed to elevate the long stretch of Alberich’s Scene 4 monologue.

The most surprising turn of the evening was William Burden in his role debut as Loge. Burden’s light expressive tenor easily brought out the beauty in Loge’s music, crowning an intelligent and highly watchable reading of the demigod as canny peacetime consigliere.

Contralto Lindsey Ammann, who is to appear in a variety of roles throughout this Ring, made a strong impression, bringing a gorgeous, rounded sound to Erda’s music. The Rhinemaidens (Jacqueline Echols, Catherine Martin and Renee Tatum) set a high standard for the evening with a consistently beautiful opening trio, a hint of the strength up and down the roster to come.

If Siegfried is the Ring’s Scherzo, conductor Philippe Auguin makes a case for Das Rheingold as (perhaps) the Mendelssohn bauble that opens the first half of the program and demonstrates what the band can do. Usual opportunities for turgid tempi like the giants’ entrance sped by, in a reading highly sympathetic to the light tone set up on the stage, though perhaps at the expense of some lost grandeur and clarity in moments like the descent to Nibelheim. The Washington National Opera Orchestra offered a thrilling sound and shone in moments like the truly exhilarating traversal of the final entrance to Valhalla.

Highlights of Michael Yeargan’s sets include the crumbling concrete portico strewn with makeshift staircases which serves as a staging area for the completion of Valhalla, a potent reminder that the struggle is real for these gods. (Wotan snoozing on the kind of dingy chaise lounge found in every cheap apartment building courtyard ever is also a nice touch.) Nibelheim is the production’s most striking visual, a towering earthen wall at which the Nibelungen scrape for gold that owes something to the scenes of the laborers in Powaqqatsi or perhaps the child mines in Temple of Doom.

Mark McCullough’s evocative lighting design creates a wealth of effects that enliven the relatively simple sets, or the mostly bare stage in Scene 4, including lights that shine up from grates that cover the entire stage. One especially beautiful effect is built around the loss of Freia’s golden apples, color slowly leaching out of a brilliant sky as the gods’ vitality deteriorates.

In general, the technical standards of this Rheingold are a considerable improvement over the earlier iteration, which may have inspired certain uncharitable wags to opine at the time that they should have called it the “Discount” Ring. These upgrades also thankfully extend to the projections which play across the scrim during transitions (new projections are credited to S. Katy Tucker). Though the descent to Nibelheim is still a bit on the nose, the new projection evoking increasingly complex chemical and biological patterns is an attractive and fitting accompaniment to the famous prelude.

Photos: Scott Suchman

Comments