Geraldine Farrar and Enrico Caruso are the leads.

Review of Pitts Sanborn in the World

Caruso Carries ‘Lodoletta’

There was diverting matter for the curious spectator in “Lodoletta,” the third new opera of the season of the Metropolitan Saturday afternoon. There was a vision of Holland – a canal and windmills always mean Holland – not as the land of the tulip, but as a region where roses blow and blow and clamber, and even wreathe the tallest tree tops. And such gifted trees. Before their efficient draperies arboriculture is abashed, diminished, dumb.

Then you marveled at a northern climate in whose beneficent embrace native and stranger behaved out of doors in glum November just as they did in merry May. Why lament the absent symbol of the Edam cheese when you could watch Miss Lodoletta, up with her namesake the lark, putting gaily to rights her American sleeping perch? Why complain this Lodoletta, tottering like a China-woman in her wooden shoes, was untrue to the simpler fashion of Dutch gaity? Why insist the Dutch discard such encumbrances on the doorstep or even wear them in a sleeping porch? O pedantry, though that killest the profits and stonest them which are sent unto thee!

If you had witnessed a dress rehearsal and wondered whether spotted fever had attacked the backdrop of canal and windmills or a plague of gnats fastened itself on Holland, you discovered measure had meantime been taken to clean the drop and clear the brave Dutch air. Never in the memory of the present scribe has Paris on a New York stage looked so nearly Paris on the Seine as the last act of this “Lodoletta,” and with an exquisite solitude for the verities of the compass the snow fell to nor’ard in larger flakes and thicker bunches than to south-ard, It was pleasant to see in the winter night shadow pictures of the dancers within waltzing across Flammen’s window shades – Mrs, Castle seemed to be of the party. But or course no Paris crowd on New Year’s eve would ever have let Lodoletta perish in the snow – that just couldn’t have happened except in an opera.

Seldom, indeed has the nameless and unsuspected malady that claims so many a hapless lady of the lyric stage seemed more gratuitous in its attack than in the case of Lodoletta. Surely it was quite enough for the good, old foster-father to suffer a fatal fall from a peach tree in Act I, while showering the rosy blooms on little children rejoicing over Lodoletta’s birthday, and then for the good wives of the village to drive the children from an innocent young girl in Act II because of an intrigue with a painter which never occurred, without handling her this sorry New Year’s blow in gay Paris. Really, that is just a bit too much! Mimi, Cio-Cio-San, Violetta, Gilda – none of that unhappy sisterhood but has her interlude of heaven. Even Lucia of Lammermoor, hounded relentlessly by the librettist, is allowed by the composer to lead the best sextet in opera and given a form of madness that brings the public up to her knees before she is at last consigned to the Ashton family tomb.

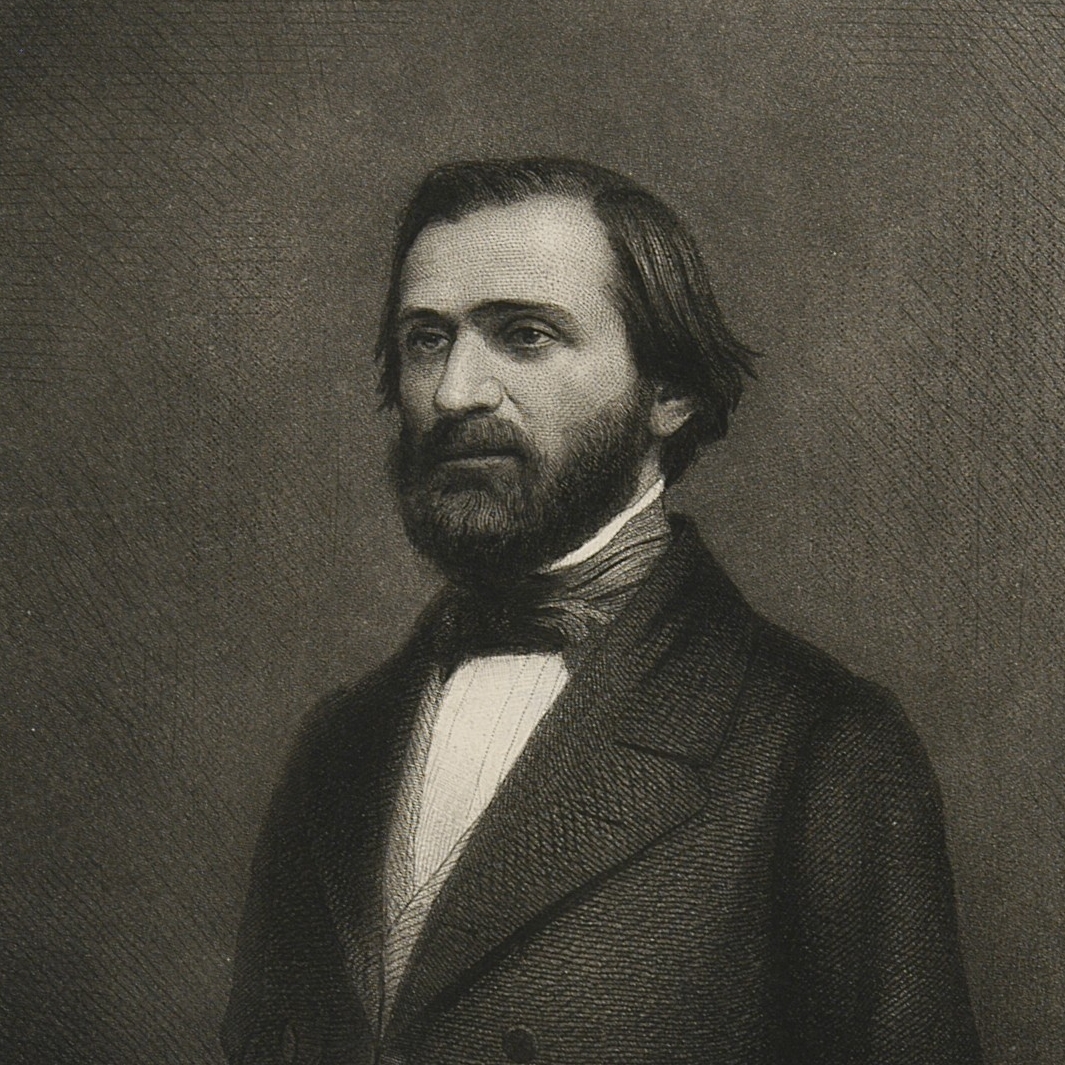

No, it really is quite too sad a good tale of “Lodoletta,” but so perhaps not quite so sad as Mascagni’s music for it. That is all hovering on the teary smile of “La Bohème,” then suddenly remembering itself, and resolutely ascowl whining a dour plaint into Othello’s fateful handkerchief, Mascagni seems to have made up his mind on no account to rewrite “Cavalleria Rusticana” only to lose himself hopelessly in a maze of treacherous Puccini shallows flanked by frowning cliffs of Verdi.

However, the music of “Lodoletta” is not pretentious, and that is perhaps the kindest thing that can be said about it. The first act, with its genuine simplicity, its pretty song for the caroling children, its soaring tenor phrases, would probably, despite the insistence on Antonio’s funeral march, seem to an opera customer not gorged with frequency to be very nice indeed. The same customer might find that second act a trifle tedious, but the third he would be sure to enjoy.

Theatrically the third is the best act of the work. The orchestra waits for Flammen’s silhouetted guests, the festive music from the street, and set off against these, the pathetic monologues for tenor and for soprano make this an effective opera act even if wanting in originality or special ingenuity. It is on this act that must hang the main success of the work, together with the fact that the rôle of Flammen is so divined that Mr. Caruso can sing it with complete ease and decidedly thrilling results.

He lived up to his opportunity on Saturday in a way that won him deafening applause from an audience which packed the house to bursting. He also looked so slender and played so naturally as the great painter from Paris that one saw in him a perfectly presentable Julien, if the Metropolitan ever gets around to producing that far worthier opera of love and painting, “Louise.”

The ingenious Lodoletta gives Miss Farrar one of the parts in which she can look and act unsurpassably, recalling by more tokens than a death in the snow the Goose Girl with which she used to beguile the drab boredom of “Königskinder.” Only her very Chinese pedestrianism of the wooden shoes marred an exquisite impersonation. The high notes of the part which are not few, she sang with more substantial and better focused tone, than has been her wont. Lower down her voice often sounded weak and reedy. Still in phrasing and expression her singing was generally commendable. An admirer balked the no-flowers rule by throwing her a bouquet from a box.

Birthday anniversaries of composers Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari (1876) and Morton Feldman (1926),

baritones Julius Huehn (1904), Theodor Uppman (1920) and Vicente Sardinero (1937),

conductor Leopold Ludwig (1908),

soprano Margherita Rinaldi (1935)

and mezzo-soprano Anne Howells (1941).

Comments