W. J. Henderson in the Sun:

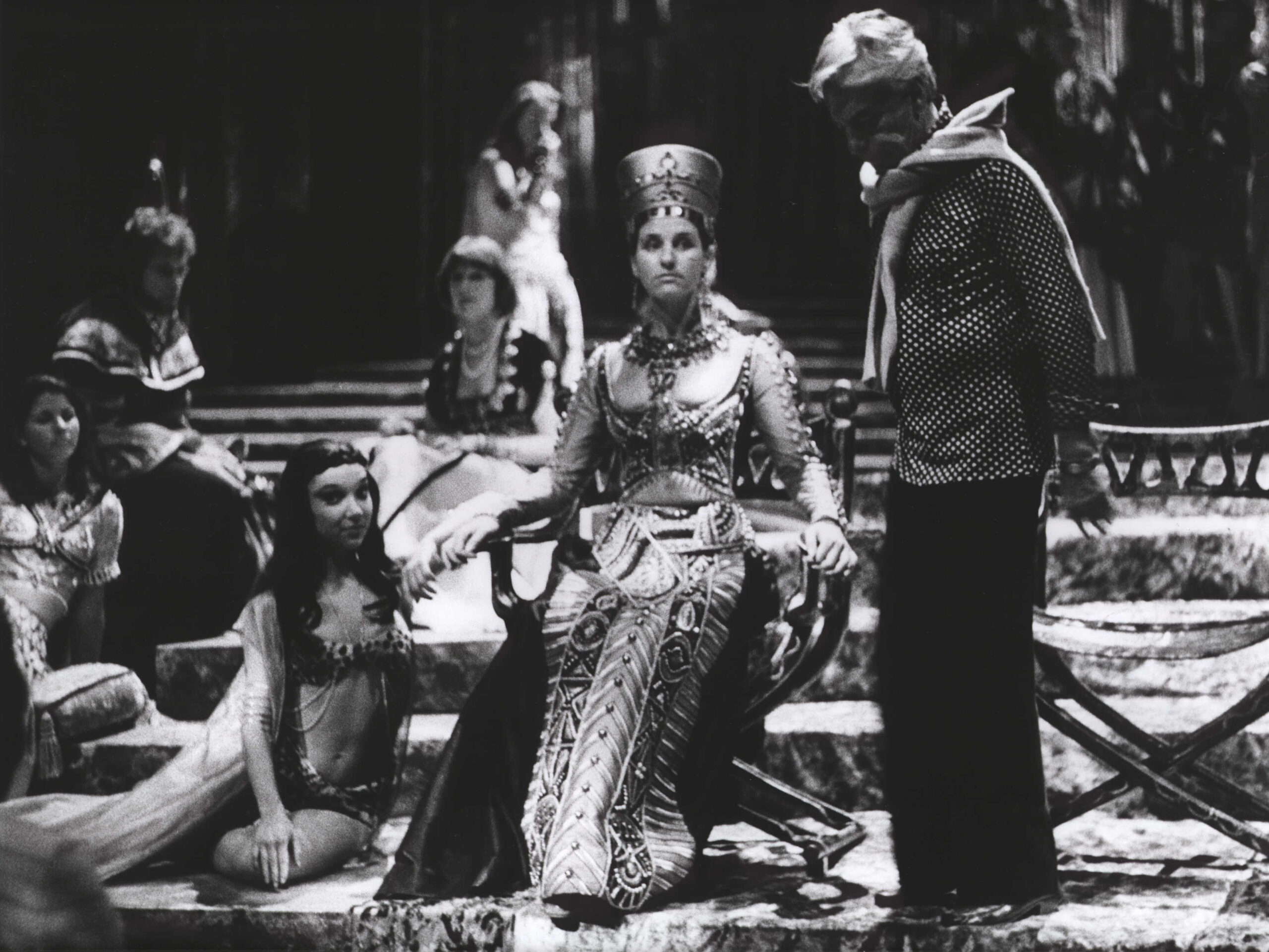

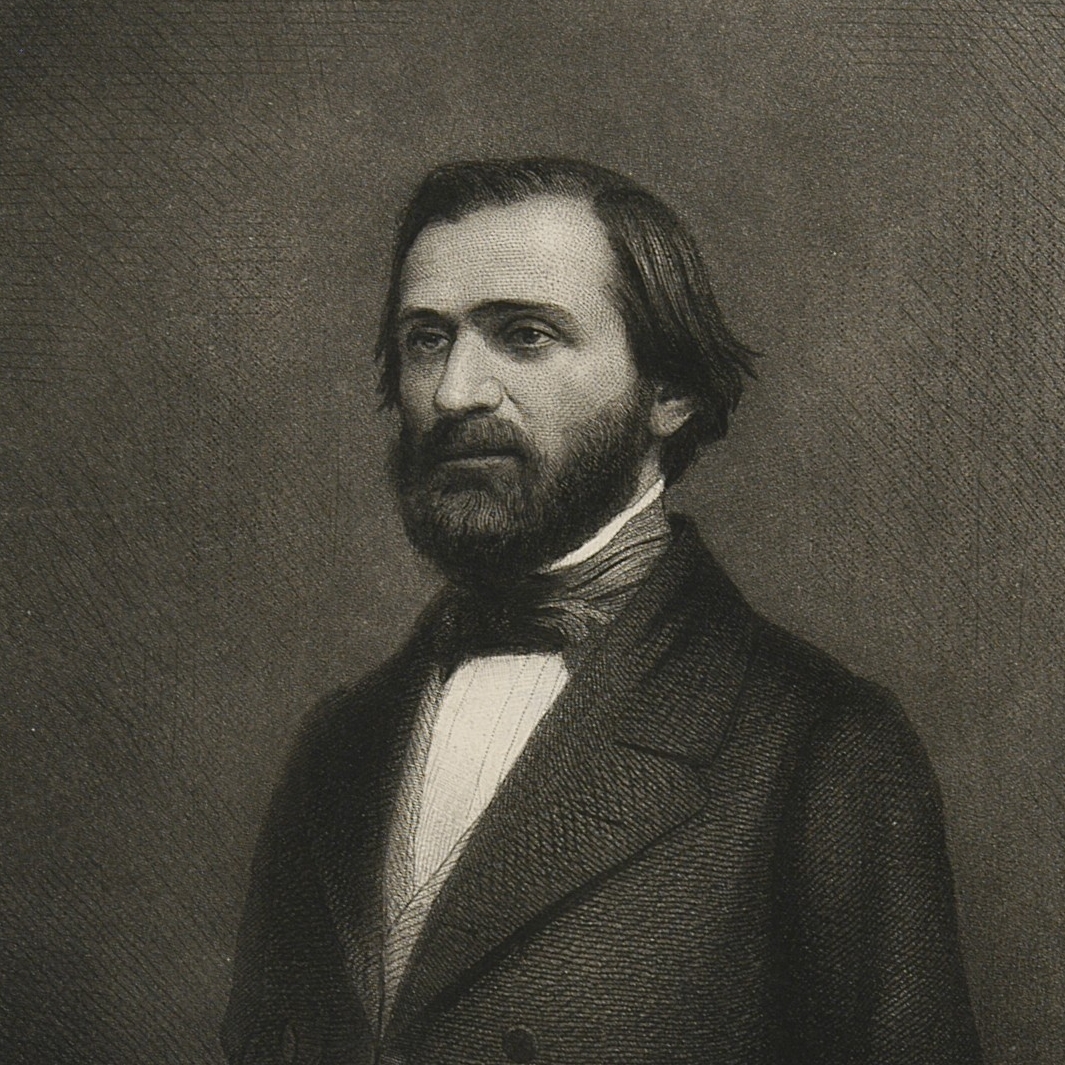

We lack the perspective now for the proper enjoyment of “Ernani.” Think of the effect of its audulatory attitude toward the holy person of a King upon the Italy of sixty years ago seething with revolutionary thought. Every line of some of its scenes had a direct message for the auditors. To us they mean nothing. Again Italy had fallen asleep in Bellini and only half awakened in Donizetti. The fierce, brutal blasts of this riotous music – riotous in its war against the refinements of true art shook the Italians from their repose and thrilled them with the consciousness of a new force. If we could hear only Donizetti for a winter, we, too, should start into a new life at the blast of Ernani’s horn.

But all the power of the work was for sixty years ago. We are listening to it in a phonographic reproduction. It is a slim whisper down the rusty wire of time. All we get out of it is the hurly-burly of its flare of brass, the bleating of its comet solos, and its blatant juxtaposition of dramatic outbursts with hurdy-gurdy dance music of the ante-Verdian stock. We cull a few bits – “O tu che l’alma adora,” “Ernani involami,” “Infelice, o tu credevi,” and the rest and mutter devout thanks that we still have some few singers who know how to voice these tunes. Then we pick out our sensations after it is all over, and decide that it is hard to be a child again, even just for one night. “Faust” and “Romeo et Juliette” – yea, even “Les Huguenots” – have made operatic old folk of us and we do not care for our little porringer anymore.

The performance was interesting, and still more so was the attitude of the audience. It was a large audience, one of the largest of the season, and it had come out with the expectation of having one of those good old times it had read about. It was worth the price of an orchestral stall to see its bottled-up enthusiasm oozing away. After a few ineffectual attempts to fan itself into a glow over the shopworn arias and duets and trios, it settled itself down to a very proper recognition of the singing of the principals.

Here, indeed, it found ample field for demonstrations of approval in the matchless art of Mme. Sembrich. She was in her own domain, her kingdom in which the royal purple of sovereign glory decks her fair shoulders. She reigned right splendidly, and all the others in the cast were but humble followers of her courtly train. She overtopped them all by the supremacy of her beautiful style, the style of the old Italian school which bequeathed to the world operas of the “Ernani” type and the school for singing them.

It would be idle to go though the score and name the airs and duets in which Mme. Sembrich’s art shone most brightly, for that method of musical chronicling is about worn out; but those who heard last night’s performance will cherish memories of her “Ernani involami” and her “Tutto sprezzo che d’Ernani” as among the brightest examples of her delivery. Such works as “Ernani” can not outlive their usefulness altogether while they provide notes for such singers. But alas! Where are the rising stars of the school?

None of the other singers was heard to great advantage. Mr. Scotti was Don Carlo, Mr. de Marchi Ernani and Edouard de Reszke Don Ruy Gomez de Silva. All of them did entirely too much singing off the key and Mr. de Reszke’s “Infelice” was extremely infelicitous. Mr. Scotti was explosive and angry in style and only once or twice did he sing a smooth cantilena suitable to the music. In fact all three of the men imported into “Ernani” the pulsatile declamatory style of the contemporaneous Italy lyric drama, and it did not fit the old lullabies of the early nineteenth century.

The chorus fell into line more easily and formed the time-honored semi-circle, retired up stage during rests and rushed down to the footlights to shout the high notes, just as choruses did when young blood ran warm in the counselship of Mapleson. Mr. Mancinelli conducted the opera with knowledge and vigor. Whatever he may think of the old fashioned music, he reverences Verdi too much to slight his work. The orchestra had no trouble in disposing of its share of the evening’s labors. The blowers of brass earned their money and much sympathy.

On this day in 1916 Granados’ Goyescas premiered at the Met.

Birthday anniversaries of writer Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette (1873), soprano Frances Yeend (1918), bass Ezio Flagello (1931), composer John Tavener (1944) and bass-baritone Spiro Malas (1933).

Comments