Irving Kolodin in The Saturday Review:

For those who have heard Miss Callas elsewhere (as well as on innumerable records) there was a basic curiosity about the marriage of the voice and the house: would they be compatible, or would there be need for a period of trial wedding? A dress rehearsal on the Saturday before left no doubt in this respect: the voice, though not a huge or weighty one, is so well-supported and floated that it is audible at all times, most particularly in the piano and pianissimo effects which Miss Callas delights in giving us. So far as “Norma” is concerned, the singer refuses to force it for volume’s sake alone, and it comes clearly to the ear even when she is ringing out a top D at the end of the trio with Adalgisa and Pollione.

The kind of voice, basically, requires some consideration. It is what every great artist’s means of communication becomes: an extension of her own personality. That personality is dynamic, highly charged, tigerish, and utterly under discipline. So, too, the voice is dynamically dramatic, produced as though it might be torn from the singer’s insides, and presided over with an almost visible concern for every word and note she sings. Nothing is thoughtless, left to chance, or without total purpose.

Factually, Miss Callas cannot afford to perform otherwise, for were she dependent on the pure physical beauty of the sound she produces she would be sung out of sight by many people presently inconspicuous. There are those who say that in the days preceding the famous diet of 1954 there were a texture and ring to the sound that it doesn’t have today. It could be so, or it could be merely a self-advertising justification for singers who refuse to diet.

In any case, what Miss Callas has to work with is an organ made in the image of a sound in her ear which demands that it be flexible, far ranging, responsive to a wide variety of inflections and intensities. It is a common analogy to compare voices with instruments-the flute for coloratura; the trumpet for such a braying tenor the Tamagno; the French horn for the rich beauty and creamy smoothness of a Flagstad. In this orchestral gamut, Miss Callas strikes me as possessed of the clarinet timbre, with the same kind of reedy fullness (and a trace of its vibrato), brilliant on top, misty at the bottom, and with the glossy agility of the black woodwind. And she works on it like a woodwind player fingering invisible keys.

With or without consideration for the tensions that must have accompanied her first appearance in a theatre to which she has aspired for a full ten years, her composure in the opening “Casta Diva” was impressive. The sound was edgy and a little shrill in the first ascension, but the artistic purpose was deeper, even more communicative than in Chicago two years ago.

There have been greater performances of this showpiece for the simple reason that the bloom and freshness to give rolling ear appeal to its lovely melodic line is not in strongest supply with Callas. But in most of those instances, a beautiful performance of “Casta Diva” was the beginning and end of the singer’s suitability to “Norma.” With Callas it is emphatically only the beginning, expressive of one aspect (if an important one) of the character she is creating.

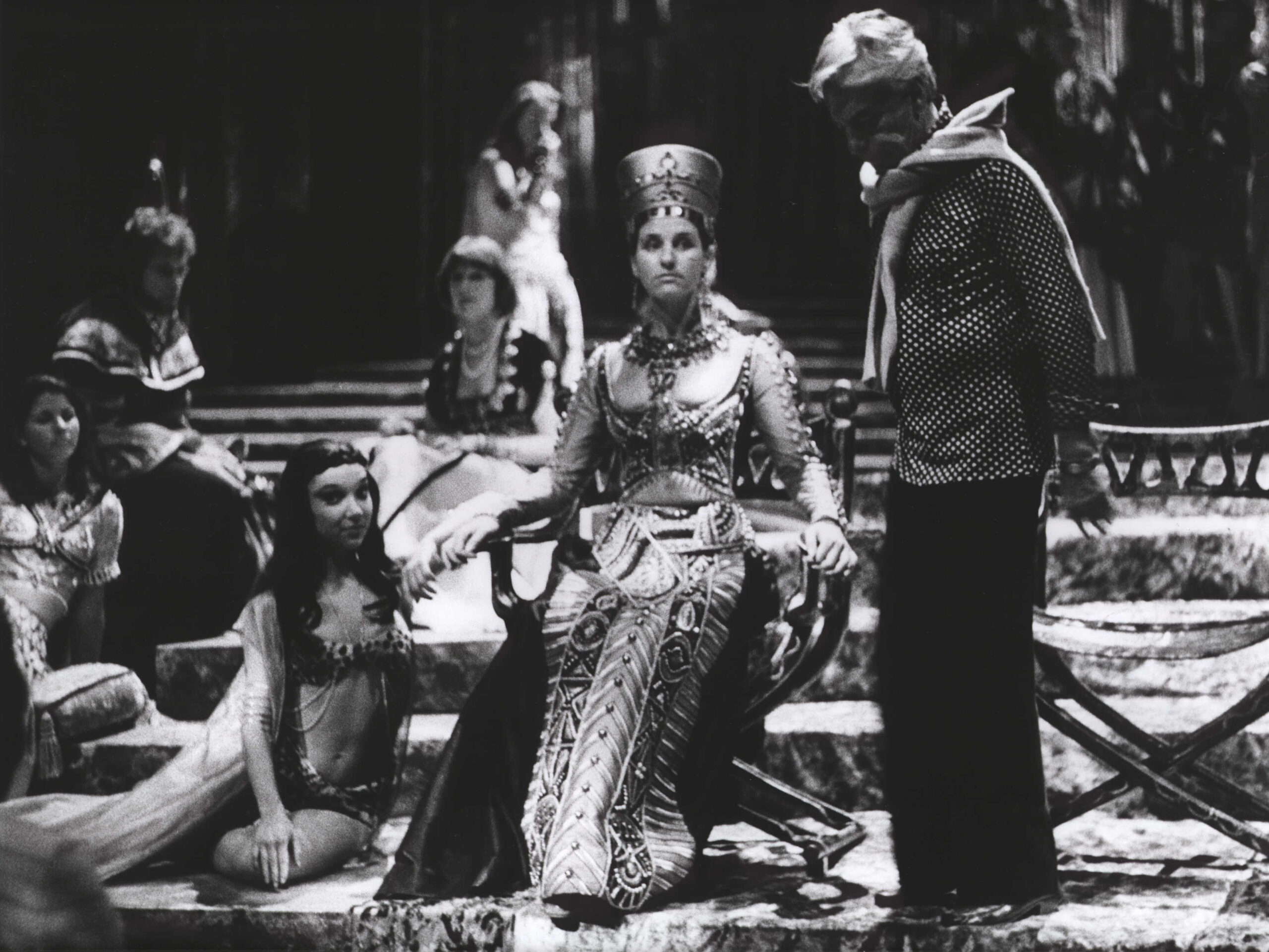

Here, of course, is the essence of what this artist is all about. Her fellow singers, all able ones, were giving performances of various degrees of vocal quality. She was creating a character as emphatically her own as Flagstad’s Alceste, or Lehmann’s Marschallin, or in another dimension Markova’s Giselle. It was something seen whole and consecutive from beginning to end. Reserved in its early aspects, infuriated in those that followed, and finally resigned to the self-sacrifice she must make to regain the esteem she has forfeited with her ill-starred love for Pollione, it finds a vocal tone to match the dramatic need in each mood. This is more than fine singing: it is dramatic portraiture of which the operatic stage has all too little.

As the foregoing may suggest, there was not quite enough of it even on the same stage she was occupying to make for a consistent or wholly satisfying “Norma,” supercharged as it was from time to time. Barbieri alone was a different singer from Barbieri with Callas, as were Barbieri and del Monaco when circumstances required them to perform with or without Norma. Consequently, the moments in which an exquisite sense of detail prevailed were rudely succeeded by those in which the loudest top note (for the tenor) or the deepest chest tone (for the mezzo) took precedence over all.

Birthday anniversaries of conductor Vaclav Neumann (1920); tenors Jon Vickers (1926) and Franco Tagliavini (1934).

Comments