On this day in 1977 Alban Berg‘s Lulu premiered at the Metropolitan Opera in the as-yet incomplete 2 act version.

Leighton Kerner in the Village Voice:

…”Lulu” has arrived as the special baby of the Met’s musical director, James Levine, and of its theatrical chief, John Dexter. With the collaboration of Jocelyn Herbert as scenery and costume designer, a production was devised that could accommodate the third act’s interscene variations and concluding adagio, which Berg had incorporated into his fully orchestrated and published “Lulu Suite.” The project would also contain important dialogue from the Paris scene of “Pandora’s Box,” second of the two Frank Wedekind “Lulu” plays on which the opera is based. Further, this production was intended to serve the complete, three-act opera once circumstances allowed or forced its release for publication and performance. Such circumstances began to take shape with the death last summer of Mrs. Berg. (She had contended that her husband’s spirit would dictate the opera’s final form in its own good time, according to a spokesman for the publisher, Universal Edition in Vienna.) Meanwhile, several opera companies from Paris to Santa Fe, have claimed first-performance rights to the complete “Lulu,” and court battles are imminent.

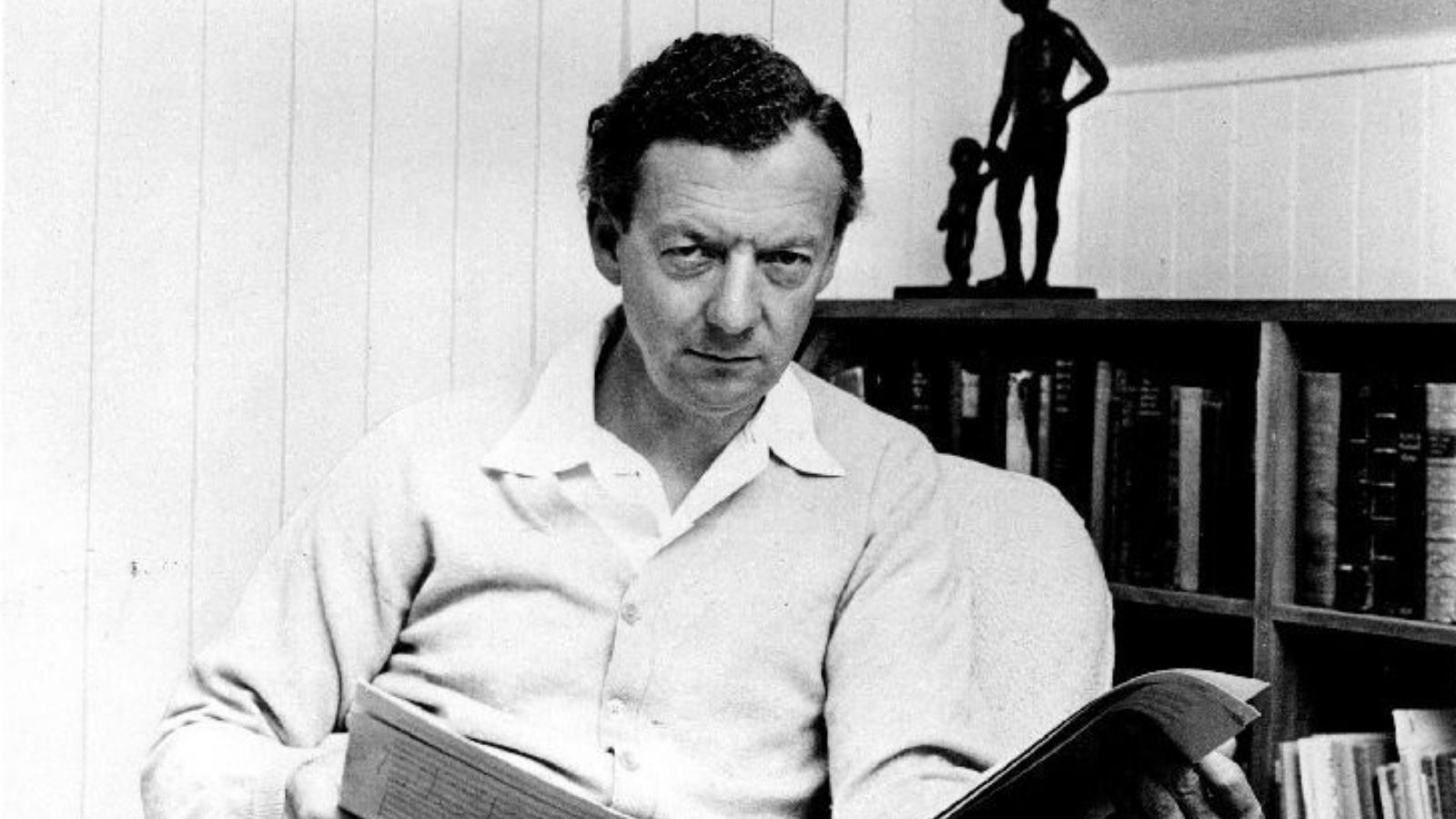

Recently Mr. Levine told me that it didn’t matter to him who did it first so much as who did it best. On the overall strength of the March 18 performance, and despite two serious casting weaknesses, I might bet on the Met to be best. Why? The main reason is the clarity and sumptuousness with which conductor Levine and the orchestra have laid out the music. This score, even in its torso form is perhaps the richest in 20th-century opera. Logically developing from the formal plan of “Wozzeck,” where acts and scenes are based on such classical structures as symphony, suite and variations on several different elements (theme, pitch, rhythm and so on) “Lulu” more ambitiously builds its forms of sonata, rondo, and the rest not on scenes, but on the individual characters; as the characters dominate or interact, so do the musical forms.

But all that becomes evident only from study. What hits you in the theatre is the mass, variety, and power of the music. At the Met premiere, the orchestra played at the top of its abilities. The strings produced rich, velvety textures on which Berg’s various dance rhythms could ride. Long, throbbing lines were spun for one of the most haunting themes in all music – the adagio that heralds the downfall of Ludwig Schoen, (in Act One Lulu’s protector and victim) and announces the entrance of his alter ego Jack the Ripper. The musical and dramatic bonds between the two men – publishing tycoon and legendary killer – and similar bonds among other characters are evident in the suppressed third act, according to George Perle, the American composer who has seen the material. Such bonds also become evident in the Met’s production, where the same singer takes the roles of Schoen and Jack as allegedly prescribed by Berg.

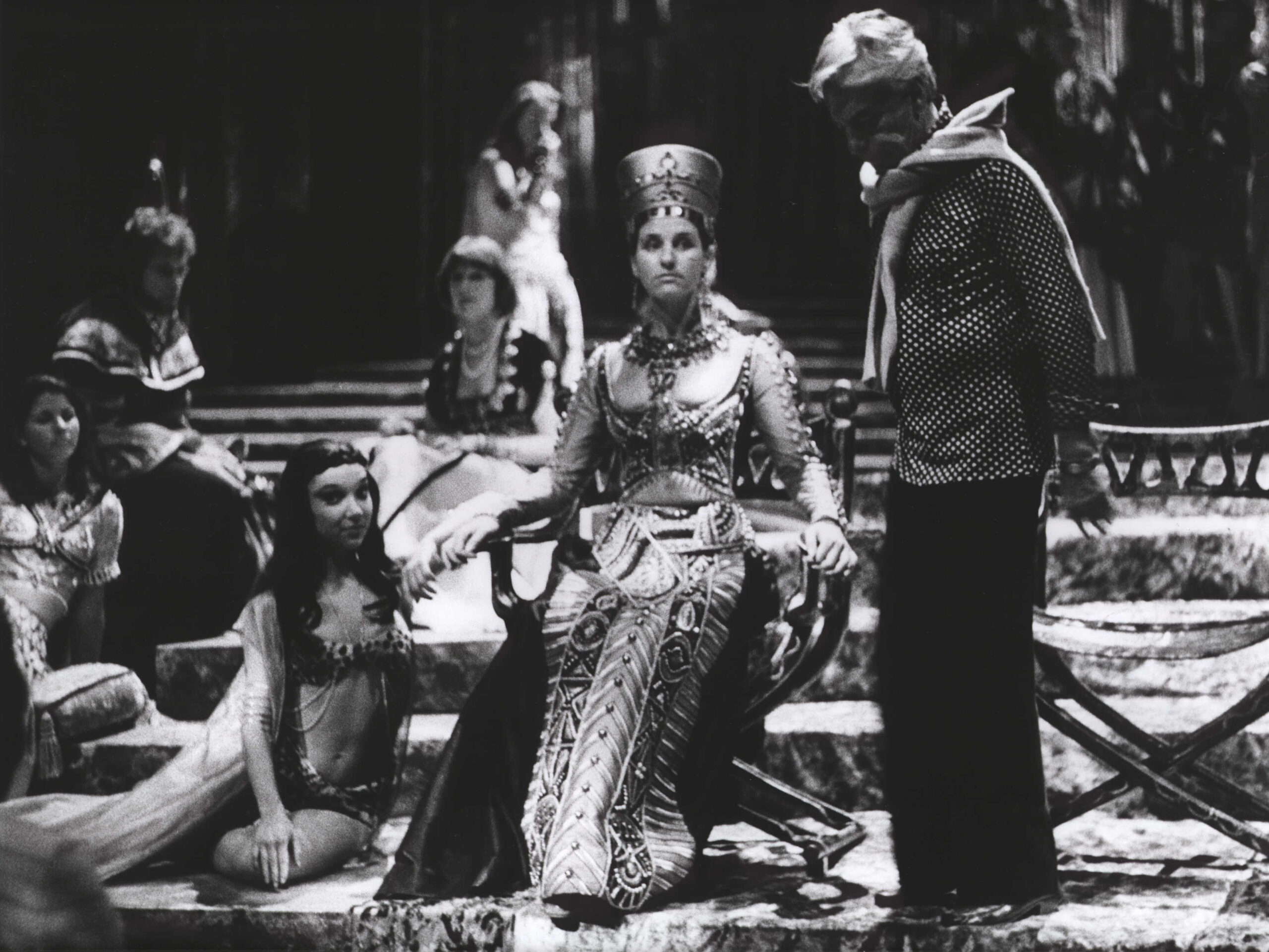

Mr. Dexter’s staging, particularly his construction of what should appear in some future season as the complete third act, fully supports the powerful projections of the music. He refuses to shy away from intentionally hilarious dialogue in such a grim fable, and, in the final scenes, he uses a cold, brutal change of costume and light to waft Lulu from a smoky Paris gambling salon to a clammy London attic. Ms. Herbert’s scenic mix of art nouveau and Bauhaus, visually mixing Wedekind and Berg, contributed no small part to the theatrical success of the event.

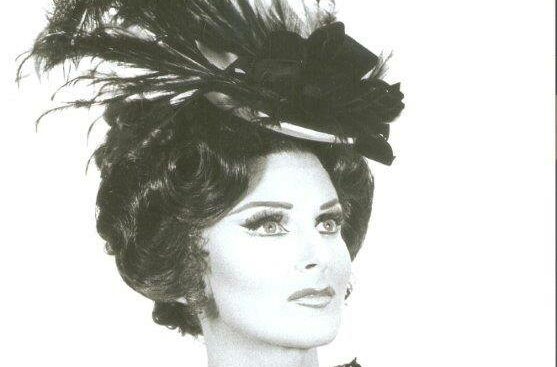

But the same cannot be said of Carole Farley in the title role. Miss Farley certainly looked as Lulu should; she has a sensational figure, and face that suggests the destructive angel of innocence. But Lulu’s high-flying coloratura-ridden, orchestra-challenging music needs the voice of the Empress in Richard Strauss’s “Die Frau ohne Schatten,” or Mozart’s Queen of the Night. Miss Farley’s sounded hard at mid-range when fighting the orchestra and painfully wiry in the flights of her second act Lied. To act the role, you need the vulnerability, though not necessarily the voluptuousness, of Marilyn Monroe as she was in “The Misfits.” Lulu must have that to drive the many men and one woman (Countess Geschwitz) in her life crazy with desire. Miss Farley seemed to act every scene literally, and her second-act credo before killing Schoen seemed a mere housewife’s plea for forgiveness and a peaceful dinner.

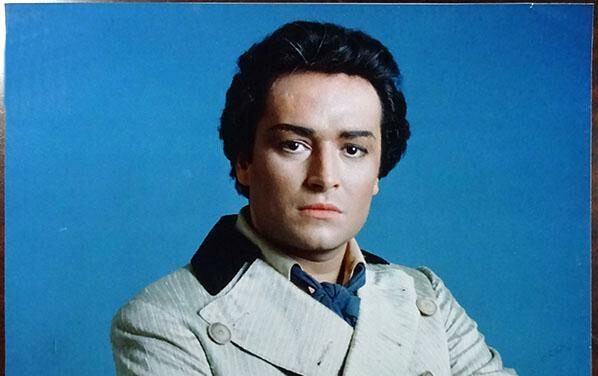

As Alwa, Schoen’s son and Lulu’s last victim, William Lewis sang his gorgeous music harshly and acted as if to avoid all the young man’s emotional contradictions. Otherwise, the night’s singing and acting were strong and meaningful down the line. Donald Gramm’s Schoen had been a triumph here in Sarah Caldwell’s 1967 English language production. Now singing in German, he has added to his previous authority and expressionistic intensity out of Wedekind, and his Jack the Ripper is the stuff of nightmares. Tatiana Troyanos emphasized that the insolent Geschwitz was a woman in constant torment, unrelieved even in her brief “Liebestod” to the murdered Lulu. Andrew Foldi, as Lulu’s father-lover Schigolch, and Nico Castel, in a vicious vignette of the blackmailing Marquis Cast-Piani, were particularly outstanding in the truly supporting cast.

Many directorial touches were scrupulously faithful to Berg, such as Lulu’s prologue appearance in the Pierrot costume of the portrait that dominates every scene. But most of the departures also worked, such as projecting cartoon stills instead of a silent movie about the complicated maneuvers that get Lulu out of jail. However, only one of the drawings looked like Miss Farley; all the others, as well as the Pierrot painting, resembled Teresa Stratas, who originally was to sing the title role but dropped out before rehearsals started.

Things like that can be fixed up and probably will be when “Lulu” returns to the Met in complete form – as it must. For the rest of the season, there’s “Lulu de Milo,” an incomplete masterpiece being performed, despite flaws, more tellingly than most of us have heard it before.

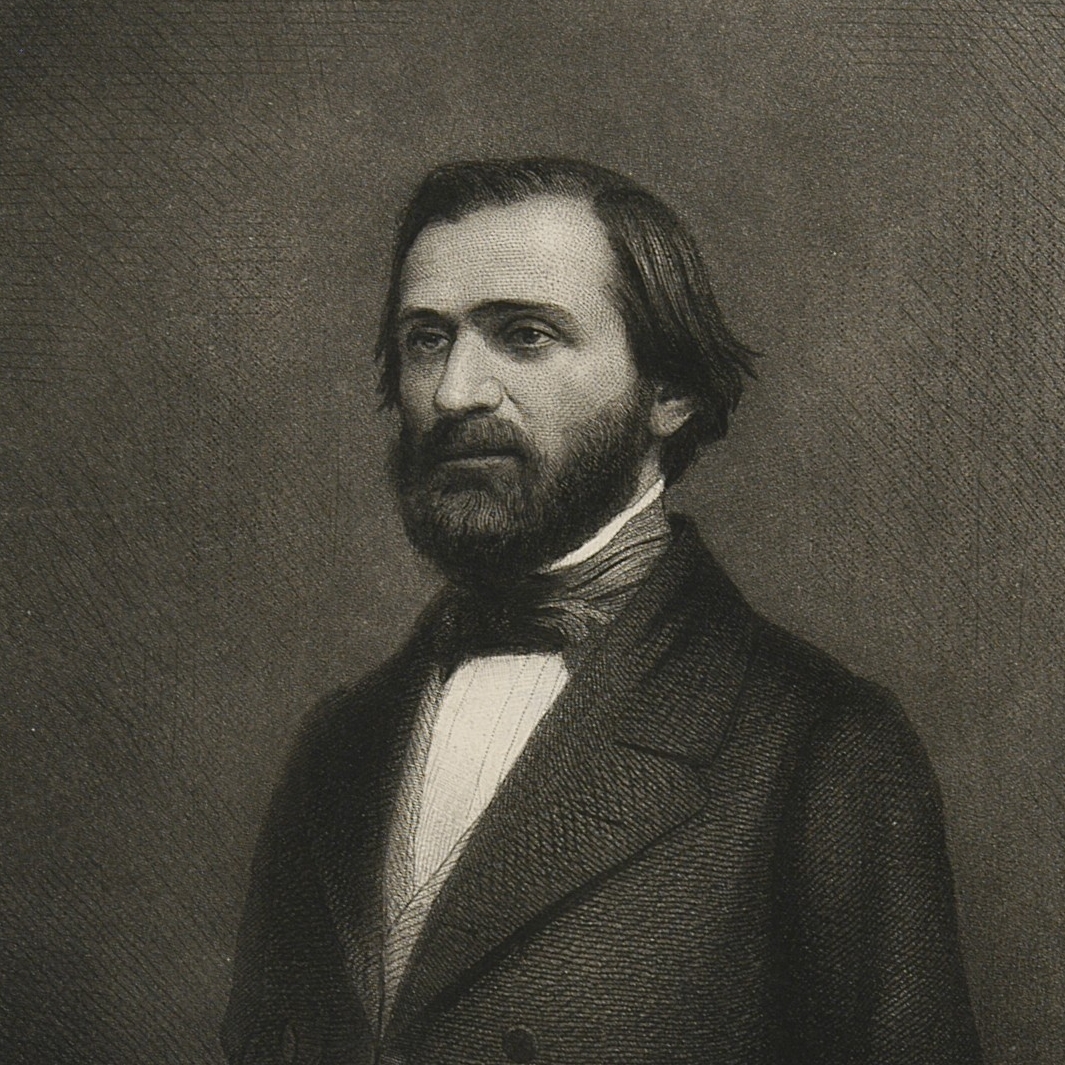

Birthday anniversaries of composers Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844) and Gian Francesco Malipiero (1882), soprano Ofelia Nieto (1900) and basses John Macurdy (1929) and Jules Bastin (1933).

Comments