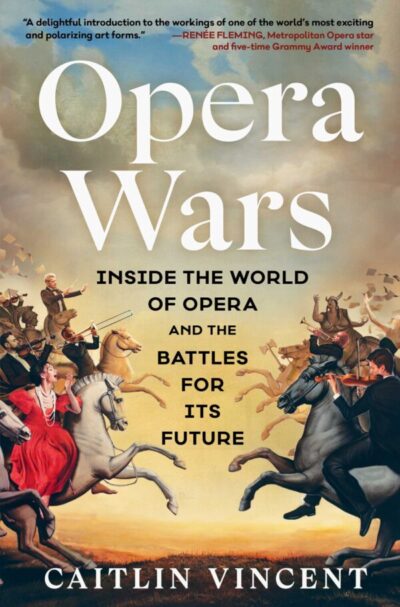

It’s not every day that my Google Search app recommends that I read a new article about opera in the New York Post, so I recently took the AI-curated bait and found a mostly reasonable summary of the challenges currently facing the operatic world. Much of the content referenced a new book Opera Wars by librettist and self-described former opera singer Caitlin Vincent. So, naturally, I had to read it.

Her aim with the book is to discuss the “reality of opera as it exists today” by focusing on what she sees as the battles and tensions that are shaping the art form. The book starts with an introduction to opera and its history, and while no one can write a 20-page overview that will satisfy all constituencies, I was extremely put off by her subsequent discussion of opera productions. For example, if you are going to claim that Wieland and Wolfgang Wagner’s Bayreuth stagings were “radical,” shouldn’t you explain what made them radical? And if you’re going to use “radical” to describe Wieland’s stagings, how does one describe Patrice Chéreau’s Ring? Conveniently, Chéreau doesn’t get mentioned at all — that is a major oversight.

Later, Vincent asserts “by the 1980s, very new stagings of very old operas were the norm” and uses the Peter Sellars-Trump Tower Nozze, a steampunk Ring (I have no idea which one she had in mind) and the Doris Dörrie Rigoletto as examples. She continues, “Stage directors played with different settings, different time periods, different characters, different plots—all with the conceit that the stage was a blank canvas, something that couldn’t (and shouldn’t) be dictated by long-dead composers and librettists.” This is certainly an extreme view of most “new” opera productions. In the early 1980s, productions of this kind didn’t even have much of a foothold outside of Germany. Moreover, the Sellars Nozze is from 1988 and played at a festival that was largely funded by Pepsico; it probably wouldn’t even have happened were that not the case. Meanwhile, the Dörrie Rigoletto was from 2005 and lasted only a few seasons.

The book spends more time on opera production, emphasizing fidelity to whatever stage directions exist in the score, libretto, or staging handbooks, which is a reasonable stance for a librettist. She does highlight that publishers are responsible for many of the stage directions that exist in a score and that there are no staging indications at all for many works. Still, she perpetuates two ideas that are toxic to a living art form: (1) There is a correct way to stage any opera and that opera goers should judge any production against a checklist (Candlesticks in Tosca? Check.), (2) Any new opera production by dint of its being new strays further from the light than whatever it replaced. Her overview would be less one-sided if she at least pointed to some positively regarded Regie productions that readers could judge. Alas, no; we just get fearmongering.

Subsequent sections are more balanced and bring perspectives from many in the world of opera. I found the discussion of blackface and yellowface helpful, particularly for her focus on the conflicting views amongst Asian communities and performers as to what they consider problematic in a staging and performance of Madama Butterfly or Turandot. She does admit that Regie is useful as an approach for presenting Butterfly without the potential cringe.

Other important topics that get covered include the grueling life of young singers and the difficult choices they make in furthering their careers, the increasing role of the singer’s appearance in casting (although I might dispute some of her timeline), and the financial challenges of opera companies, including the problems caused by conservative tastes of mega donors.

The book closes with a discussion of opera’s perception in popular culture with Vincent noting that too many potential operagoers are intimidated by unfamiliar works. But for new operagoers, aren’t all works are unfamiliar? Even if they recognize “Nessun dorma,” they probably have no idea that it’s from Turandot. But that fear of “new works” seems to be abating. Even Vincent herself acknowledges that Met premieres have strong ticket sales. But what we don’t know is whether these newer operas are drawing in new audiences or bringing lapsed attendees back. She also points to the ineffective marketing by most opera companies. The Met has finally tried to cultivate influencers, but I wonder if the algorithms will eventually gatekeep their content. Vincent has no silver bullet to offer. Will books like this one entice the opera-curious? Perhaps, if they don’t get the impression that most opera performances subvert the creators’ intentions.

Nonetheless, the timing of this book could not be better with many of the challenges discussed in the book surfacing at the Metropolitan Opera in recent weeks. The Met has announced another round of budget cuts and the potential need to take more drastic measures as the deal for the Met to tour Saudi Arabia could fall through. Meanwhile, The New York Post, smelling blood, published an opinion piece lambasting the Met; the article (by a politics reporter) criticizes Gelb for producing too much woke content, ruining the opera Carmen by moving it into the present day, and firing Anna Netrebko.

None of these grievances, all sourced from anonymous insiders, surprise me. What did catch my attention were new claims that Gelb is an indecisive micromanager and that “Nine [wealthy] families keep the Met alive in New York City.” I do suspect there is a faction of the board that is unhappy enough with Gelb, whose contract was recently extended yet again through 2030, that they are feeding content for a hit piece to the Post which is all too eager to sling mud on their behalf. So in that regar, we may have a genuine Opera War on our hands. Stay tuned.