Steven Pisano

First, there is the countertenor. There used to be very few singers in this category. You could name the notable ones on one hand or less, and they scarcely ever appeared in the opera house. It wasn’t clear how you did use them, since few composers had specified their music for one. Great was the debate over whether countertenors could match the achievements of the castrati (I think they can and do, but … I’ve never heard a trained evirato, surgically altered to suit the task, and neither has anyone else you’ve ever met) and whether a male countertenor not so altered can match or surpass a female alto in the same artfully heroic roles.

And then there arrived a starburst of countertenors and sopranists, trained to a superb degree and capable of singing just about anything. Dozens of them. Hundreds—with distinct qualities and talents. Once you’ve got as many in the opera house as the traffic will bear, how do the rest pass their time? We’ve heard them sing in rock cabarets and do solo performances of Le nozze di Figaro and replace Cherubino or Octavian and perform Schubert songs and rock anthems in drag—appealing to a mixed audience or not.

The second problem is the operatic voice itself in this age of the microphone. Is there still an audience for the natural sound, generated by the singer without electronic assistance? Yes, to be sure, but how large is that audience? And if opera lovers prefer an unamplified sound, and the abilities of a naturally produced voice (I certainly do), to what purposes outside the traditional repertory and the traditional opera house can such well-seasoned instruments be turned?

All these matters were idling through my mind when I attended Ritual: Schwarze Messe Kabarett/Black Mass Cabaret the Friday before last (the first of three performances) at the Cell Theatre in Chelsea. Ritual was the third installment (I missed the previous two) of a series of programs/performances designed to bring out the queer perspective in the history of operatic performance under the heading “Counter Codex,” “created to reclaim queer narratives in opera.” The singer at the heart of these collaborations is Jordan Rutter-Covatto, star of Counter Codex.

The first production, Erato, focused on music of the Italian baroque opera world—and we all know how much use those narratives made of gender-bending and transformative characters, changing their sex or their orientation at will, usually by magical means, for whatever purpose, usually seduction or disguise. The second production, Polymath: La Comedie de la Mort, turned to such composers as Berlioz and Duparc (among some contemporary guys) to depict the queer community’s response to the ordeal of AIDS.

Ritual focused on another aspect of queer history: the invention of a “queer science” in twentieth-century Germany. There, a certain Magnus Hirschfeld, an openly queer researcher on sexual psychology, studied homosexuality and its position in many societies. This sounds dry; the performance was not dry. (There were even drinks available.)

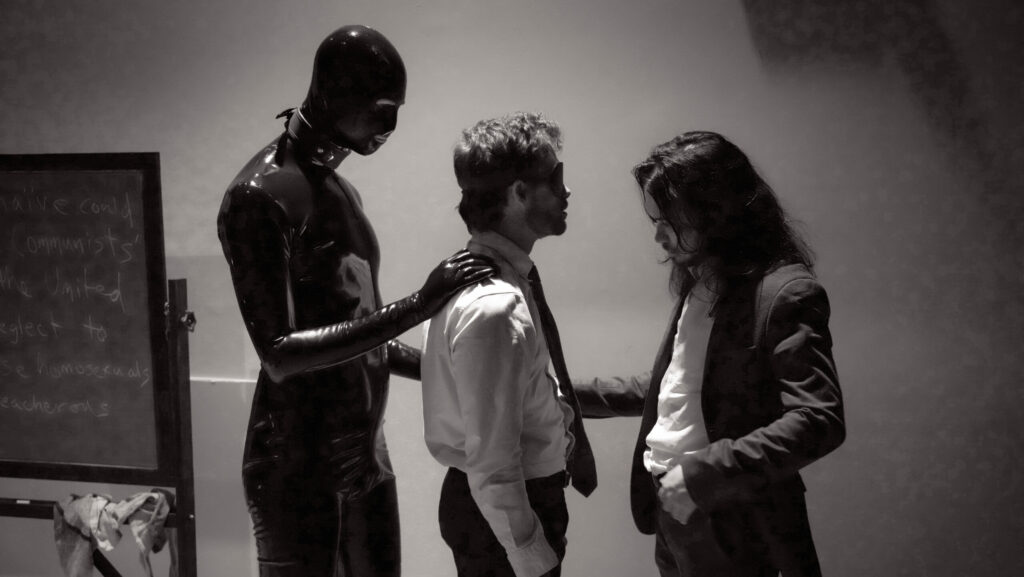

Steven Pisano

Ritual, the third installment, dealt with the brief, intoxicating openness of the Weimar Era in post-war Germany, the ensuing rise of Fascism that oppressed sexual freedom along with so much else, the closet that bloomed in secret during and after that period (including the McCarthy Era’s pernicious scandals) and so to the more open modern era.

The music performed, besides arias from a number of Bach cantatas, was otherwise largely the work of Jewish (and sometimes queer) composers of Germanic extraction, from Schönberg and Friedrich Hollander to Viktor Ullmann and David Begyglman, two men who composed at the “artistic” concentration camp of Theresienstadt and died at Auschwitz, and on to Kurt Weill, a Berliner who fled to Broadway, and Mischa Spoliansky, a Russian who fled to Berlins.

The principal musician animating the series is Rutter-Covatto, a countertenor who has sung with many baroque ensembles but has been in search of new worlds to conquer. His instrument is not especially sensuous, and he has not seen a path forward in the operatic realm. He acts persuasively and expressively, but the voice lacks a quality to match, say, a mezzo soprano in the same music. Undaunted, he has adopted the accoutrements of the leather scene to portray grotesques of the Weimar Era and the martyrdoms of the Nazi period that crushed it. His choice of music is fascinating—I did not know the Ullmann or Beyglman songs and found his performances insinuating and appealing. The Weill and Spoliansky songs were also moody and inspiring.

Aside from the work of Lotte Lenya, we know very little of the rich satiric and political cabaret repertoire of the Weimar Era. Rutter-Covatto sings Ullman’s and Beyglman’s songs with a hectoring energy that reminds us (subtitles appeared on the walls) of the bitter wit of protest. He does not attempt to make the sounds beautiful; he reminds us of the acid experiences that gave rise to them and contrasts with the snarling operettas of the period.

The actors Max Richards (playing a sometime scientist—Magnus Hirschfeld, perhaps) and Peter Cage (silent, but imposingly head to foot in black vinyl) contributed to scenes of the experiences these songs (sung by Rutter-Covatto, harnessed in leather) might illustrate. A lively instrumental trio (piano, woodwinds, cello) backed the musical side—they began with a Meyerbeer overture; although there was nothing Jewish about the music, the enlightenment air of Berlin in the era of Napoleon prepared us for the inventions and developments that followed. The director of the project was John de los Santos.

The Schwarze Messe Kabarett struck me as a work in progress, startling in its visual and aural imagery (if naked men on the concert stage still shock anyone), incomplete in its decisions of what to satirize and how to bring these declarations into a unified artistic whole. An intent and crowded audience seemed to be tickled by the music, the performance, the cheerfully sordid atmosphere of “This is your history—revel in it!”