I attended Wednesday’s second performance, and it was a deeply satisfying way to spend a five-hour afternoon.

This production emphasizes the growth of Siegfried from childhood to manhood. The first act set (original scene designer Johan Engels, fulfilled by Robert Innes Hopkins) is not the expected gloomy cave of Mime, but an oversized playroom complete with blocks, toys, an oversized playpen, and a scrim in the background covered with cartoon drawings.

Siegfried is a bumptious child dressed in shirt, shorts, and tennis shoes. It only took the audience about 5 minutes to buy into this concept, much helped by the brilliant performance of German tenor Matthias Klink as Mime. Klink’s was a Mime of wild physicality, scampering and gibbering across the stage, singing and acting with marvelous attention to detail.

His tortured love/hate relationship with his ward Siegfried has never been more clearly limned, and Klink used an unusually wide palette of vocal colors to create a truly three-dimensional character.

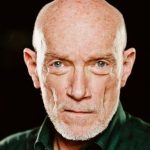

German tenor Burkhard Fritz, making his American operatic stage debut in the title role, seemed at first an odd piece of casting. He certainly doesn’t have the look of a young hero, but here he plays Siegfried as a petulant child with only the most rudimentary understanding of the world.

Fritz plays the role with humor, energy, and a wonderful sense of utter innocence. I had seen a couple of reviews of the opening night saying that his voice and presence seemed too small for the role, but I think he must have had opening night jitters, because yesterday he poured forth lovely tone. Only in the huge orchestral climax to the Forging Scene did his voice get lost in the orchestra.

Speaking of the forging scene, since Mime’s forging is inadequate, we need some modernized equipment in order to reassemble the sword Nothung. So the forging tools, complete with pictorial instructions a la Ikea, are brought in by the troop of costumed actors that serve the entire production. All the boxes of equipment have all the hallmarks of Amazon Prime, but are labeled “Rhein Logistik.” See “tongue-in-cheek anachronisms” above. The effect is delightful.

Also illuminating Act One is the stately entrance of The Wanderer, made ever larger by Eric Owens singing the role on stilts, giving him a regal and a bit frightening appearance while flawlessly handling his movement on the stilts. Owens’ characterization of Wotan/ Wanderer has achieved great depth over the course of the first three Ring operas, and here he sings with smoothness and power as well as a wounded vulnerability as Wotan begins to see his world crumbling when we reach Act Three.

In the second act, we meet again the Nibelung dwarf Alberich (a snarlingly effective Samuel Youn) here played as homeless, pushing a shopping cart full of his belongings, including his severed arm in a plastic tube, still plotting how to regain the Ring stolen from him by Wotan.

But if it’s Act Two of Siegfried, everybody’s waiting to see The Dragon Fafner. And Pountney’s dragon is formidable indeed, a giant inflated head with piercing eyes and pointed teeth, plus actors manipulating its claws and tail. And in a first for this reviewer, a human emerges as the dying Fafner pierced by Nothung.

Bass Patrick Guetti sings with a robust, deep bass and manages to make us actually feel sorry for Fafner’s demise. The Forest Bird, here brilliantly manipulated by an actor on a long flexible pole, flutters and soars. And, in this production, we also get to see a human version of the bird manipulated by Wotan, sung with clarity and shimmering beauty by Diana Newman.

And Klink’s Mime returns frustrated by the fact that Siegfried can now hear his inner thoughts,and is stabbed with Nothung as he tries to steal the Ring and the Tarnhelm. Klink even manages to die humorously.

Following the stirring orchestral prelude to Act Three, Wotan returns to waken the “earth mother” Erda, who emerges from the depths on an ascending platform, the actors making her enormous gown shimmer. Lyric debutante Ronnita Miller sings Erda with powerful low notes and strong presence, though her high notes thin out and quaver.

Then in the glorious second scene, Siegfried finds Brunnhilde, removes her armor, and, in Fritz’ best moments of the evening, tries to make himself kiss the sleeping Valkyrie to awaken her. It’s here that Siegfried learns what fear is, simultaneously learning how to be a man.

Christine Goerke is a marvelous Brunnhilde, singing with clarion power while using her silvery soprano to reflect the many emotions of the conflicted girl. And Fritz matches her beautifully, leading her from doubts and fears to embrace her womanhood. The end of their duet was thrilling, the audience bursting into spontaneous applause as boy gets girl.

Sir Andrew Davis led an authoritative, nuanced performance of this difficult and complex score, and the Lyric Opera Orchestra rose to the occasion with aplomb. The strings and woodwinds were particularly effective, and the brass section rang out save for a couple of minor glitches.

Splendid contributions are made by lighting designer Fabrice Kebour, using bright, splashing primary colors contrasting with the dim scenes surrounding the dragon. Costume designer Marie-Jeanne Lecca delighted with her colorful, detailed, phantasmagoric clothing. Choreographer Denni Sayers does outstanding work with the 17 actors who add so much to the proceedings.

Photo: Todd Rosenberg