| I was not allowed to see Carol

Neblett's

scandalous debut as Thais. My parents thought I was too young to view La

Nebletto's strip tease routine. Yes, dear reader, I was that young.

Given how I turned out, my parents are still banging their heads against

the wall for not letting me see the Big Blonde in the buff. Her singing

was reportedly variable, but in the words of Lanfranco Rasponi, she "delighted

the audience by baring her breasts."

The Bourbon Street strippers were anything but delighted,

however, and picketed Neblett outside the opera house. If they were required

to wear panties and pasties by law, how did that soprano broad rate? Just

whose dick, they mused, was she sucking? Well, we really haven't the space

here to discuss that particular topic, but I have often wondered why ever

she was cast the following season as Gounod's Marguerite. Now, Thais is

one thing, but envisioning Neblett as the village virgin required some

unwilling

suspension of disbelief: she sauntered into the Kermesse scene looking

like some medieval Jayne Mansfield. Maybe the girl can't help it, but Neblett

as Marguerite was all wrong. With a getup like that, no wonder Valentin

was so worried.

"O mio babbino

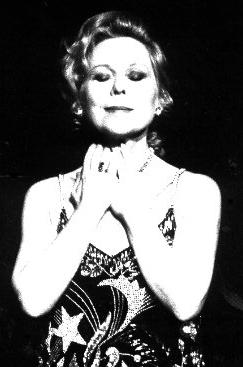

caro" ( as sung by Renata Scotto)- La Scottisima

never sang a staged opera for New Orleans Opera but she did appear under

the auspices of the company in a gala concert with orchestra. The year

was 1981 and the diminutive diva was traveling with the Met on the Deep

South portion of its annual tour. So between performances of Manon

Lescaut in Memphis and Dallas, Scotto jetted into town for this

one-night-only extravaganza. My grandmother bought me an orchestra Backstage, Scotto struck me as a correct, polite woman

who could also be aloof and a little chilly. As she signed my copy

of her Norma recording, she spoke enthusiastically about

her upcoming opening night at the Met in the same opera. Little did we

know the fiasco that loomed in povera Renata's future. Before parting,

I suggested to Scotto that Minnie in La fanciulla del West might

be a good role for her. She frowned and said, "I dun know. Is a heavy,

heavy role for, how you say in America, a has been?" Perhaps she heard

my suggestion as an insult. If so, that was not my intention. I adored

Scotto. I have no praise high enough to offer this sublime donna who taught

me what the pursuit of every artistic endeavor should be: la verita.

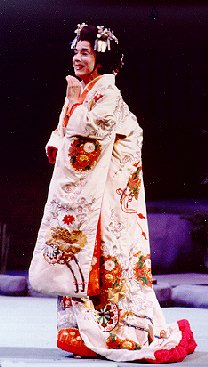

Delicate, lavender-colored lyric soprano Jeanette Pilouwas a regularly featured artist of Bing's final seasons at the Met. A dark, exotic looking woman, she was the product of French and Egyptian parentage. She made some sporadic appearances at the Met during the 1980's (including a touching Melisande), but is now seldom remembered today. 'Tis a pity because Pilou did some notable work for New Orleans Opera. She sang Cio-Cio-San in 1973 and brought many individual touches to her portrayal. She wore her long, black hair down at the top of Act Two, a daring innovation that caused a buzz among the seasoned opera goers. (Remember, this was a few years prior to the Ponnelle film and the concept of a self-Westernizing Butterfly was still unusual.) This performance was my first evening at the opera and Pilou led me to expect well-considered interpretation from all future divas, not just emoting by the numbers. Pilou returned years later to sing a vocally troubled performance of Massenet's Manon. Her fragile voice had obviously suffered from incessant forcing and the top notes were now blowzy and effortful. When she emitted an eardrum-shattering war whoop in the Hotel Transylvanie scene, a dozing patron awoke, exclaiming: "I thought Jean Fenn was retired." It seemed a wasted evening until the final scene. Then,

the curtain rose on the most poetic setting I ever saw at New Orleans Opera,

an autumnal scene of fallen leaves and woodland solitude. Here, Pilou died

in the arms of her Des Grieux, a muted sunset silhouetting her final spasms.

I wept at the fate of pauvre Manon that evening. As she poured out her

guilt and shame for giving into all manner of forbidden impulses, I saw

my own conflict as a gay man mirrored in Pilou's performance. How hard

would society slam me for heeding the call of my own taboo desires? This

Manon

marked an important juncture in my coming out process and for that I will

always appreciate Pilou, war whoops and all.

Sturdy, reliable Louis Quilicosang practically every New Orleans Opera season during my formative years. With his solid if unthrilling baritone, Quilico was easily taken for granted. But I remember many an evening when he was the class of the cast. There was an Ernani From Hell "starring" Renato Francesconi and Claudine Carlson. Quilico came out in the third act and tore the place up with his invocation before the tomb of Charlemagne. You were so starved for some real vocalism that Laid back Louis was received with grateful relief. He similarly rescued a Pagliacci production from the efforts of Nancy Shade and Harry Theyard. Although Quilico sang Verdi most frequently with the company,

I remember him more vividly as the besotted Herode in Massenet's Herodiade.

He

sang the famous "Vision fugitive" with tangible rapture. I remember

how he rolled about with orgasmic delight as the sultry saxophone introduced

the aria. For once, I didn't see a tubby man feigning ecstasy, but a convincing

depiction of unbridled lust. This Herodiade was a well-received sternstunde

for this easily forgotten fixture of the New Orleans Opera.

Katia Ricciarelli, the great lirico-spinto hope of her generation, debuted with the New Orleans Opera during the 1974-75 season as Mimi (her signature role). At this stage of her career, Ricciarelli was presenting herself for the first time to opera audiences throughout the world in a variety of roles, ranging from the Trovatore Leonora to Micaela. In those years, she could be somewhat gauche as an actress and her singing lacked the refinement she would attain only a few seasons later. There was a persistent beat in her voice that detracted from the golden sound. Nevertheless, Mimi was a perfect role for her and her characterization was most appealing. She played Mimi as a naive and eager jolie fille, not the doomed tragedy queen. She possessed an unaffected charm and naturalness that endeared her to the audience. The luminous glow of her timbre seemed to cast a soft radiance over the hall. Ricciarelli was clearly a singer with promise and she

satisfied all expectations a few seasons later at the Met with memorable

portrayals of Desdemona and Luisa Miller. Who could forget the Otello

broadcast with Vickers when Ricciarelli floated the high A-flat at the

end of the "Ave Maria" for what seemed like an eternity? You could almost

see James Levine grinning. Ricciarelli's prime was all too brief but the

promise of those early years was considerable.

I first encountered the Soviero magic in my capacity as stage manager for her 1984 New Orleans Opera debut in La Traviata. I was somewhat familiar with her work through several radio and television appearances with the New York City Opera. By the time of these Traviataperformances, Soviero had just ended a ten year apprenticeship with City Opera and was embarking on a long-delayed international career in hopes of reaching the Met within a few seasons. Diana's husband Bernard Uzan was the stage director and flew into town several days prior to her arrival to make sure all was in readiness for the rehearsal period. He spoke passionately of Diana's abilities, describing her numerous triumphs in opera houses everywhere. At the time, I thought his comments a touching and gallant case of biased perception. I soon revised my opinion. Diana tore into the first sitzprobe like a woman possessed. I knew she had sung Violetta dozens of times but she drank in every criticism, every suggestion, every detail offered to her by the maestro. She sang out full voice, without marking. She was in character at all times. A small but very shapely woman, Soviero radiated confidence but was never intimidating or arrogant. She was chic, stylish and very Italianate (to paraphrase La Bumbry, her arms were flailin' all about the place). Her spoken Italian was beautiful but her English still carried delightful traces of her New Jersey origins. As rehearsals proceeded, I knew I had never seen an artist work as truthfully as Diana. Cliched though it may sound, she was the first to arrive, the last to leave. All of this diligence served to highlight two qualities she possessed that I consider to be the sine qua non of a great artist. First, she was blessed with an innate musicality that is instinctive, not appliqued. She not only hit the notes, she commanded them. She phrased with rubato, made sensitive use of dynamics and understood how accento can be just as exciting, if not more so, than mere decibels. Second, she was a born actress. She knew that all great acting comes from really listening and reacting to one's colleagues. She was alert and aware of her surroundings at all times. Most importantly, she played something other than the given about her character and her situation. How often I had seen "Sempre libera" played by unimaginative Violettas who laughed maniacally as they twirled around the stage, lapping up Sprite out of a plastic champagne glass. The febrile giddiness of the music is already there in the music--it doesn't need to be underlined with silly business. The intent of the cabaletta is to communicate Violetta's despairing retreat into hedonism as a response to her awareness of impending death. But how many Violettas have the intelligence or the inspiration to play such subtext? Diana did. I will never forget how she pulled flowers from a large vase, shredding their petals as Alfredo's voice penetrated her defenses, finally burying her sobbing face in the destroyed remains of the flowers, a perfect visual metaphor for this young life ravaged by illness and self-destructive behavior. As a stage manager, I was usually much too absorbed in the task of calling cues to pay much notice to what the artists were doing on stage. But every night when I signaled the curtain after "Sempre libera," there were tears pouring silently down my face. Diana would return in future seasons to deliver a definitive

Cio-Cio-San and heartbreaking Mimi. Illness robbed us of further planned

appearances as Massenet's Manon and Desdemona, but I treasure what did

come to fruition. I remember the last night of the Traviata

run, sitting with Diana on Violetta's deathbed, waiting for the Act Three

prelude to begin. We talked about many things. She was off to Vienna the

next day for performances of Liu at the Staatsoper. She regretted her lonely,

hotel-confined existence but had committed her life to being an opera singer.

Her idol was Renata Tebaldi but she also had been influenced as a girl

by her father's Muzio recordings. We both revered Renata Scotto and expressed

outrage at her hideous treatment by the New York press and public. I told

her that Scotto was my diva of the moment but maybe one day Diana would

hold sway over my adoring heart. She laughed and we shook hands on it.

Well, I'm happy to say that, while Soviero has not displaced dear Renata,

she is the diva of the moment in my singular affections.

I still can't believe I actually heard Richard Tucker perform but I'm glad to say it's true. I saw the great tenor in one of his rare appearances as Eleazar in La Juive during the 1973-74 season. I was eleven at the time, only two years before Tucker's untimely death. The role had great personal meaning for Tucker and the Met lent him some of the costuming worn by Caruso in his final Met performance as Eleazar. Tucker gave an overwhelming performance, demonstrating conclusively that an unimaginative singer can be transformed into a titan when the music or drama speaks to his soul. Tucker understood the suffocating atmosphere of the closet and his portrayal of the outwardly compliant Jew practicing his forbidden religion behind closed doors touched me in ways I did not yet understand. The lightning-quick way Tucker alternated his duplicitous

dealings with the oppressive Christians with tender concern for his adopted

daughter was the instinctive work of someone who has known persecution.

The inner torment of this complex spirit poured forth like lava in the

well-known "Rachel, quand du Seigneur." The audience rewarded the verity

of Tucker's performance with an ovation. Don't ever let anyone tell you

Tucker wasn't an artist. Any singer who exposes his vulnerability so bravely,

so movingly is worthy of every accolade.

Lucille Udovich-

Lucille who, you ask? Never heard of La Udovich, you say?

A Glyndebourne Elettra? Turandot in the Corelli film? Still scratching

your head? Well, you can stop--I never heard Udovich either. She came to

New Orleans in 1964 to sing an Aida with Sandor Konya and

Oralia Dominguez but I was only two years old. I mention Udovich because

she represents a whole category of valuable artists who were overshadowed

in their day by giants like Callas, Tebaldi and Milanov, but now, in retrospect,

sound like Golden Age material. New Orleans opera welcomed a number of

these underappreciated divas during its first few decades, including Stella

Roman, Inge Borkh, Phyllis Curtin, Margherita Roberti, Gianna D'Angelo,

Leyla Gencer, Virginia Zeani, Gabriella Tucci, Adriana Maliponte, Raina

Kabaivanska and Gilda Cruz-Romo. The sad irony of being a junior opera

queen in the 1960's and 1970's was that I took a lot of singers for granted

who deserved more respect than they were accorded. The mere mention

of some of these ladies during their respective eras would have drawn scorn

or laughter or both. But in the debased age of Victoria Loukianetz and

Angela Gheorghiu, someone like Mary Costa is starting to look like a goddess.

Although she did not spend many years in her home town, Shirley Verrettis the most famous native-born female singer the Crescent City ever produced. She made her 1980 debut with the local opera company under rather frenetic circumstances. Alexandrina Milcheva had canceled her appearances as Carmen as the last minute. Through some combination of managerial finesse and good timing, Arthur Cosenza persuaded Verrett to step into the lurch. Rumor had it that she had her own personal agenda: to return Carmen to her repertoire away from the international spotlight, as well as to visit relatives she had not seen since leaving New Orleans. Verrett came, saw and conquered as Bizet's gypsy. She looked and sounded like a goddess and, given the harried rehearsal situation, was surprisingly at ease. Tickets had been sold out for days, audience excitement was high and Verrett earned a standing ovation at opera's end. Verrett returned in 1983 as Tosca. This was the first production I had ever stage managed on my own and I was scared to death. Shirley was a dear, though. She calmly reported anything she thought was a problem and offered sage wisdom about how to get it resolved. When Verrett's rented costumes were deemed unwearable by the diva, she instructed me on how to contact the Met and have her own personal costumes shipped to New Orleans. They arrived the day of the first performance but Shirley took it all In stride. No, she had no plans to come to the theater early for fittings. "We'll, manage, darling," she said to me by phone. "I need my rest, so don't expect me before 6 p.m." This diva was unflappable. Verrett had a rare ability to do the prima donna routine right, without all the off-putting nonsense that lesser divas felt compelled to resort to. Her hauteur was innate and organic, not the phony camouflage associated with some other divas ("I was bohn in Owgoosta, Georgia"). She had a delightful grandiosity that was endearing, not laughable. On day over lunch, she informed me with a perfectly straight face that Elisabetta was her role in Don Carlo, not "that lady with the eye patch!" Alas, our Tosca was a mess. The stage director had never directed a complete opera before and it showed. There were other problems, as well. Our Cavaradossi, a cute little Italian tenor named Beniamino Prior, Prior was the gay equivalent of a skirt chaser and spent every available pausa putting the moves on supers and ballet boys. At the final dress rehearsal, I was distributing lists of the planned curtain calls to the artists' dressing rooms. Upon entering Prior's room, I heard the the door close behind me-- and there stood the hairy tenor, completely nude, his dick erect and ready for action. Before I knew what was happening, Prior was on top of me, thrusting his tongue in my mouth and unzipping my pants. Suddenly, Verrett pounded on the door, calling Prior's name. Oh, great, I'm thinking to myself. Shirley Verrett wants to consult with the tenor and he's about to give me a blow job--that'll help my career. Quickly zipping up my pants, I beat a hasty exit, leaving one frustrated tenor and puzzled prima donna behind. Verrett rose above all the backstage craziness. She was

grateful for my efforts on her behalf. On opening night, I found a long-stemmed

rose on my desk with a sincere note of thanks from the diva. Your most

welcome, Shirley. And thank you for all those fabulous Ebolis and

Azucenas.

Frau Kammersangerin Claire Watson, an American soprano who concentrated her musical activities mostly in Germany and Austria, appeared rarely in the United States. Surprisingly, she sang most of her American performances with the New Orleans Opera. She debuted with the company in 1969 as Arabella and made subsequent appearances as Ariadne (1974) and Elsa (1976). By the time I heard Watson's Ariadne and Elsa portrayals, I was already familiar with her performances as Freia and Gutrune on the Solti Ring recording. She was an aristocratic figure on stage, noble of bearing yet very feminine and appealing. She was vocally somewhat past her prime but she imbued both roles with the same ethereal purity and spiritual dimension that Elisabeth Grummer, Lisa della Casa and Leonie Rysanek brought to their classic interpretations. Although her appearances with New Orleans Opera would be counted successes, they were not without their problems. Watson was confronted with some rather trying circumstances that she probably did not encounter in Munich or Vienna. At the end of the love duet, Ariadne and Bacchus rose to the heavens on a little circular elevator. The effect was magical: the lights went out on stage, the set flew into the wings, Watson and the tenor began their ascent into the firmament and an electric starburst exploded over their heads as the music reached its climax. The curtain descended . . . a long pause ensued . . . what was holding up the curtain calls? The curtain flew out again, revealing Watson and tenor Jean Cox trapped on their little elevator, now looking decidedly garish in the harsh work light turned on to assist in their rescue. A stagehand came out with a ladder and propped it up by Watson's feet. However, the diva gave him a withering look to indicate that Kammersingerins in togas do not climb down ladders with their behinds facing the public. The curtain came down yet again, the singers were duly rescued and the curtain calls proceeded without further delay. In typical New Orleans fashion, the stagehand with the ladder was given his own bow. As Elsa, Watson was plagued by another common New Orleans menace, something known as "New Orleans Throat" (not to be confused with " Moffo Throat ", although some of the causes are similar). In fact, almost every artist who came through New Orleans suffered to some degree from New Orleans Throat. The city's marshy location and tropical climate created humid conditions that were often intolerable for singers. Watson coped admirably with her bout of this condtion, even when veteran mezzo Nell Rankin as Ortrud tried to take advantage of Watson's indisposition by upstaging her during their Act Two confrontation (in a screaming purple dress, no less: by this point in her career, Rankin needed cheap stunts like this to create any effect at all: her voice was no more than a husk.) With her old world charm and elegance, Watson graced the

limited Germanic operatic repertoire that I heard in my youth. She braved

the inherent hazards of operatic life in our fair city and went on to deliver

some splendid performances. Given her few appearances in her suol nativo,

I count myself lucky.

Diva and Divo X-You know them: the last-minute substitute for the famous artist you bought a ticket to hear. No one has ever heard of them but the opera house management assures us in their pre-performance hype they triumphed in places like Mobile and Toledo. New Orleans Opera presented many Diva and Divo Xess in my years there. When Nicolai Gedda canceled his Faust performances, we got some character named Jean Bonhomme. When Galina Vishnevskya canceled her Tosca, we heard the "renowned" Roberta Palmer. New Orleans didn't always rebound with a loser. There's

the afore-mentioned Verrett substitution. I also remember the little-appreciated

Matteo Manuguerra filling in for Renato Bruson as Rigoletto. Manuguerra

was sick as a dog himself but still impressed with a moving, intelligent

portrayal. Cancellations occasionally yield unexpected but rewarding results.

Joann Yockey

was the local diva done good. New Orleans has had its fair share; in addition

to La Yockey, they included Linda Zogbhy, Audrey Schuh and Phyllis Treigle.

These native-born sopranos usually triumphed with New Orleans Opera in

roles like Micaela or Musetta, nabbed a few prestigious gigs elsewhere,

then settled back into lives of domestic bliss as local society matrons.

I saw all these homegrown prima donnas. While Zogbhy was clearly the most

talented of the lot (she sang Mimi and Ilia for several seasons at the

Met), Schuh had the longest career. She was still singing Micaela as late

as 1976, some thirty years after her debut with New Orleans Opera. She

was perhaps a little long in the tooth for the jupe bleu

and the natte tombante, but her presence in the cast was

a tribute to the enduring power of the locally produced diva.

I have no hesitation in describing Teresa Zylis-Gara as the most ravishing-voiced soprano of my experience. Now largely forgotten by queens of the current generation, this Polish prima donna was an enchanting fixture of Met broadcast seasons throughout her sixteen year career at that house. With her satin-textured, sherry-colored sound, Zylis-Gara lent distinction to any performance she appeared in. Her most celebrated role was Donna Elvira, but I will always cherish a Tannhauser Elisabeth I heard Zylis-Gara sing in her final season at the Met (1983-84). Nobody ever sang "Dich, teure Halle" like her. NOBODY. Rysanek may have made a vacation of the high B, but Zylis-Gara flooded the senses from first note to last with a gorgeous outpouring of creamy radiance (and her high B wasn't chopped liver, either). By the time of her 1980 debut with the New Orleans Opera as Adriana Lecouvreur, Zylis-Gara could do little wrong in my book. I went to the theater that evening prepared to encounter an adored friend, known intimately but never seen. My heart was pounding with excitement as Cilea's gossamer strings accompanied Zylis-Gara's center stage entrance. I applauded feverishly and felt no shame when the uncomprehending beoti in the audience shushed join me. Although she lacked the temperament of a a Scotto or Soviero, Zylis-Gara impressed with her palpable glamour and sophistication. I rushed backstage, determined at last to know what a genuine diva looked like up close. The deserted stage was lit by naked light bulbs and the dingy hallway outside the artist's dressing rooms contained none of the cheering fans I expected to encounter there. Summoning up all my courage, I knocked on the door marked "Miss Zylis-Gara." A lilting voice responded: "Yes?" The door opened and there stood the first diva I ever saw in the flesh--so to speak. She was dressed from head to toe in leopard: leopard shoes, leopard coat, leopard turban, leopard everything. She had the most dazzling blue eyes I have ever seen. As I introduced myself, they sparkled with anticipation, illuminating her broad, attractive face. I stammered my praise for the performance, told her how I came to admire her through her many Met broadcasts and what a dream fulfilled it was to see her at last. Zylis-Gara embraced me tightly and kissed me with delight on both cheeks. "You are so kind, dear boy," she exclaimed. "I love you." Somebody wake me, I thought. As she autographed my stack of records, photos and memorabilia, we chatted about future engagements and possible new roles. I escorted her to the stage door. As she stepped into a waiting limo, I went stumbling into the night intoxicated by my brief encounter with this muse in human form. In the fall of 1983, I was an assistant stage manager when Zylis-Gara returned for three performances of Cio-Cio-San. She was the kindest, least difficult soprano I ever worked with. Everyone backstage respected her, even the precocious boy playing Dolore. When Zylis-Gara attacked a high note forte and caused little George to clap his hands over his ears, the soprano immediately did a diminuendo on the same note to spare the boy further injury. A caring gesture by a classy artist. Junior queens may be interested to know that Zinka Milanov, known to be sparing in her praise of other divas, considered Zylis-Gara the finest soprano of the 70's. Those intrigued by this remembrance are directed to her portrayal of the Composer in Ariadne auf Naxos for EMI. If the duet with Zerbinetta doesn't bring a lump to your throat, you've been warped by too many evenings with Maria Ewing. No piece about my junior queen years in New Orleans would be complete without mentioning the diva who started it all way back in 1970, glorious Grace Bumbry. When I was eight years old, my grandmother took me to see the Karajan Carmen film at the Saenger Movie Palace on Canal Street. If opera is my religion today, then that film was my first communion. La Bumbry was my first taste of the delicious, intoxicating way of life known as diva lust. I love you, Grace Bumbry. And when I die, I want someone to play your recording of "O don fatale" at the funeral of this formerly jeune andouille. |

||

seat

as an early birthday present. Decked out in a rented tux and toting armfuls

of Scotto memorabilia, I set off on that beautiful May evening to see the

great cantatrice of my junior opera queens years. Scotto's program was

a brief one, interspersed with numerous overtures and interludes. She sang

scenes from Otello and Ballo in the first half,

verismo arias in the second. Her encores included "Un bel di," of course,

but the one I remember best was a delectable "O mio babbino caro." As she

walked out from the wings, some queen yelled "Norma!" Scotto

stopped in her tracks, winced, managed a pained smile, whispered "no" and

proceeded to take her place next to the maestro. An elderly woman teetered

up to the stage and offered Scotto a single flower, as if to make amends

for the offending request. Scotto beamed, signaled the conductor and began

the aria. As she caressed her cheek with the flower and flashed a charming

smile, Scotto displayed a rarely seen girlishness that provided a welcome

contrast to her usual haughty demeanor.

seat

as an early birthday present. Decked out in a rented tux and toting armfuls

of Scotto memorabilia, I set off on that beautiful May evening to see the

great cantatrice of my junior opera queens years. Scotto's program was

a brief one, interspersed with numerous overtures and interludes. She sang

scenes from Otello and Ballo in the first half,

verismo arias in the second. Her encores included "Un bel di," of course,

but the one I remember best was a delectable "O mio babbino caro." As she

walked out from the wings, some queen yelled "Norma!" Scotto

stopped in her tracks, winced, managed a pained smile, whispered "no" and

proceeded to take her place next to the maestro. An elderly woman teetered

up to the stage and offered Scotto a single flower, as if to make amends

for the offending request. Scotto beamed, signaled the conductor and began

the aria. As she caressed her cheek with the flower and flashed a charming

smile, Scotto displayed a rarely seen girlishness that provided a welcome

contrast to her usual haughty demeanor.