Xerse, a work of 1654, was presented over the weekend by the Yale Baroque Opera Project at the University Theater in (of course) New Haven. It’s been a few years since I caught one YBOP’s presentations (this is their eleventh year and fifth Cavalli work), and a great deal has changed. Someone has spent money on sets, costumes, lighting—and spent it very elegantly—and the large cast, some of them still students, performed to a remarkable standard. The theatricality of the production and a remarkable number of fine voices made this, my ninth Cavalli opera, a standout.

The opera was deceptively familiar, as the Nicolò Minato’s libretto was re-used by other composers as late as 1738, when Handel gave it the setting that has been among the most popular baroque opera revivals, the one that begins with his “Largo,” “Ombra mai fu.” The text of this familiar aria opens Cavalli’s opera as well, and the rest of the plot works out much the same.

The festivities began with the usual entreaty to turn off electronic devises, on this occasion sung à la Cavalli (one of the maestro’s own tunes purloined, is my guess), by the program’s director, Sylvia Leith, later the afternoon’s Amastre, who sang it in the proper style, goat-bleat trills and all. We, the entreated, felt we had been most courteously and creatively approached.

The stage director, Dustin Wills, divided the story into two parts. As you may recall from Handel’s opera, the story concerns Xerxes, king of kings of Persia, attempted conqueror of Greece. Herodotus depicts him constructing a bridge of boats across the Hellespont in order to march westwards. This is the climax of Act II: The bridge destroyed by a mighty storm, and Wills takes advantage of it to demolish his set and remove Kate Noll’s proscenium, that reduced the action to intimate foreground confrontations.

After intermission, we found ourselves in the brick-walled backstage with a couple of barebones props. Have you noticed that low flats representing turbulent surf might, if raised into the heavens, resemble the clouds of a serene sunset? Well, lighting designer Solomon Weisbard has noticed, and dyed them pink and purple accordingly.

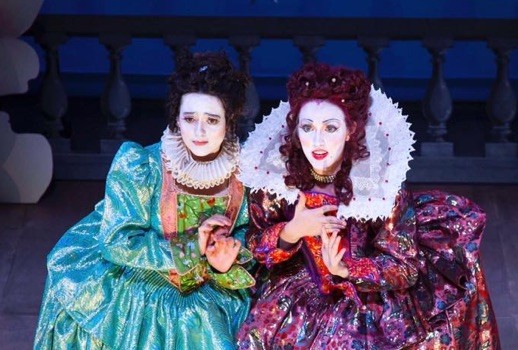

By this point, the characters had lost Seth Bodie’s glittering and stylish seventeenth-century costumes and tore about in nightgowns or elaborate underlinen, exposing their emotions. In short, phony courtly behavior was stripped away, and we beheld the subconscious at play. You’ve seen this before, it’s a cliché, but at Yale it was very well achieved and served the important theatrical purpose of giving us new things to look at after intermission.

The intricate costumes and carefully poised baroque formal attitudes were beginning to be tedious (100 minutes of Cavalli is 100 minutes of Cavalli, all solo, nary a duet in sight). Wills’ stagecraft saved the day, even if not quite congruent to the libretto’s fixations. And in the remaining act, we had a couple of duets for comic and serious lovers.

You remember the story: There are two brothers, Xerxes (here Xerse), King of Persia, and Arsamene. Both of them want to marry Romilda. Ariodate, Lord of Abydos, has two daughters, Romilda and Adelanta. Both of them want to marry Arsamene. There is also Xerse’s jilted fiancée, Amastre, disguised as a (male) soldier to keep an eye on the treacherous king.

There are lots of servant roles for comic business—only one survives in Handel and only four made it to Yale. Everyone writes letters and gives them to servants to deliver; the letters always go awry; therefore we have confusion if not exactly development. There is also an amorous tree, but it does not sing; it is sung to. There is a happy ending, so obviously Xerse never makes it to Athens or Sparta.

In this production, there was a winged mime, representing Love. Arsamene, who had earlier torn a Cupid doll to bits to express his disgust with love, enters carrying the full-size Amor, trying to wrestle him off (ah, what a director can do with a youthful cast!). Love pummeled him back, and shot arrows at everybody. At last Adelanta entered with a bow slew Love, thus vowing her commitment to celibacy.

The singers were young, attractive and, most of them, impressively gifted. Ariadne Lin, the Romilda, has the pure, focused, recorder-like sound of an Early Music specialist; her laments were limpid and moving. Courtney Sanders, who sang the conniving Adelanta, had a more powerful sound, but lacked the exquisite coloration of the romance’s heroine. Sylvia Leith’s Amastre never allowed bitterness to shroud her fine, bright soprano. Abigail Sneider sang clear, blithe lines as Cleta, the sisters’ servant, and Yingxue Wang produced bell-like soprano phrases as Xerse’s favorite eunuch.

Kohl Weisman cut an attractive figure as the romantic and frustrated Arsamene. His baritone is pleasing and agile, a welcome variation among the high voices of the other four lovers, but of course this was a transposition to suit modern taste: In Cavalli’s time, royals were always sung by higher voices, female or evirate. It has not been the custom at Yale Baroque to give such roles to countertenors—altos have been the rule—perhaps because the school does not have mature countertenors to perform them.

Jack Lundberg, who sang Xerse on this occasion (bejeweled and be-laced in the traditional gold—including platform heels), demonstrated the problem, possessing neither a mature sound and effective projection nor much acting ability. Inaudible and immobile in his first scenes, he loosened considerably in the more hectic doings of Act III, his voice, too, gaining size and confidence. But he gave, nonetheless, the only less than adequate performance of the afternoon.

Tenor Paul Steffan was winningly confused asAriodate, the father of the bride—but which? And to whom?—and bass Raphael Laden-Guindon made sympathetic the role of Amastre’s confidante, Aristone. Jeremy Weiss, a winning ham, stole every scene available as servile Elviro, who must disguise himself as a flower girl, strew blossoms, mix up messages, stand on the bridge of boats while the storm destroys it, steal ornaments from that famous plane tree and seduce Cleta the servant girl into the bargain.

He never flagged. His voice, alternatively shrill or gravel, does not strike one as operatic, but his singing was full of character in several ranges and reminded us that the serious-buffo division had not yet been established. Cavalli’s operas cheerfully mingled both.

Grant Herreid led an orchestra of seven other musicians and kept the singers in order while they leaped through the staging’s hoops.

Though exploring the vast trove of pre-Mozart opera is a great success all over Europe, and companies or festivals devoted to such works flourish in Boston, the Bay Area and Toronto, New York continues to lack a group focused on this repertory. Considering the size of New York’s opera- and Early Music-loving communities (and our stable of talent), this seems a waste of opportunity, to say no worse. For the lovers of baroque opera in New York, the annual YBOP production is a reliable pleasure, a two-hour train ride away. The singing earns high marks and the tickets are free.

Photo via Facebook.

-

Topics: yale baroque opera project

Latest on Parterre

MET Opera Legend Leona Mitchell Live in Concert

Leona Mitchell, the MET Opera’s leading Verdi soprano for 18 seasons, is returning to the stage April 19th in New York City. Get Tickets →

Leona Mitchell, the MET Opera’s leading Verdi soprano for 18 seasons, is returning to the stage April 19th in New York City. Get Tickets →

parterre in your box?

Get our free weekly newsletter delivered to your email.

Comments