What is surreal, symbolic, and generally mysterious in the dramatic arts can get a bad rap. The approach is regarded with suspicion if not irritation by many, especially (though not only) in the staging of repertory works. Just tell The Story in an easily comprehensible way, some will say. Don’t “distract” me. Don’t make me wonder what something “means” or “represents.”

This is a shame, I feel. Even when I cannot immediately account for every image in a film by Luis Buñuel or David Lynch, or, closer to home, in an opera production by Stefan Herheim or one of the Alden brothers, the work of those artists at their best rewards engagement. What they present us has a power of its own; it compels, tantalizes, haunts. Perhaps something will have different associations for different viewers.

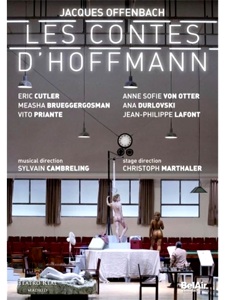

But some dreams are more worth sharing than others. Christoph Marthaler’s 2014 production of Les Contes d’Hoffmann for Teatro Real de Madrid, newly released on DVD, is worse than a dream that fades; it’s a dream you have on a night you don’t remember having dreamt. If some detail of it should bubble up, you wouldn’t tell anyone about it, because you’d have an awareness that the soggy grounds on the filter of your subconscious are of no interest.

The prologue, all three acts, and the epilogue take place on a single set designed by Anna Viebrock. It is an Art Deco café evoking Círculo de Bellas Artes de Madrid, but really just a vague “interior.” At times it could be a theater, a studio, a pool hall, a restaurant, a transit station; it can be several of those things and more at the same time.

Supernumeraries wander in and out; props are carted to and fro. Singers shuffle around in the familiar enervated Marthaler fashion, hands in pockets, eyes cast down (the Frantz performs his whole aria that way, completing several slow laps around the perimeter of the set). Often two singers are lined up stiffly for an exchange, side by side and not looking at each other, or they’re seated and hollering across a distance. There is a great deal of sit-and-sing.

In the prologue and the Olympia act, artists at easels sketch nudes, ignoring Hoffmann and the other characters. Luther occasionally leaves his station behind the bar to walk over to the nudes and hand them tissues to wipe the perspiration off. Luther himself, a big fellow, shows some skin of his own with an in-sight costume change for Crespel duty. A reproduction of Jump from Lefkada is center stage. The models are off the clock by the opera’s halfway point, but they’re still milling about with open robes. There is a row of theater seats upstage and at stage left, sometimes empty, sometimes occupied.

I suppose Marthaler should be given his due for achieving and sustaining the desired tone(lessness). From time to time there is bizarre action, like a bit in the prologue with waiters dancing spasmodically, and a group of people in the Giulietta act surrounding a billiard table and taking turns slowly diving face first onto it, but connections are inscrutable. I cannot accuse the staging of desperation, because that would imply a higher energy level and a clearer motivation to communicate something.

The Muse sings that it is time to transform herself into Hoffmann’s friend, Nicklausse, and struggles to pull on a pair of pants, but then just gives up. Drag: who can be bothered anymore? That futile abortive gesture gives some sense of the whole undertaking. Marthaler has emptied Offenbach’s work of its phantasmagorical elements and not filled it with much to replace them beyond anomie and tedium.

The spectators come and go, usually looking bored. When we come back to Hoffmann in the epilogue, his audience is dozing. Stella, who had been sauntering around as a distinctive, accusing face in the crowd all night, finally speaks, rebuking this romantic (and Romantic) artist with a passionate political recitation, an excerpt fromFernando Pessoa’s Ultimatum.

Perhaps Marthaler wants us to consider a theme of indifference to art, of “sightseers” who only shallowly engage with what they are presented. If so, he has undercut himself; I was firmly on the side of the supers who had nodded off. The people in the theater seats for the Giulietta act stare stonily ahead from behind 3D glasses, but the DVD comes with nothing to give the production an additional dimension. Pity.

The musical performance does not rescue matters. I would prefer to pass lightly over the singing. No one sounds very good in this mélange of small voices, damaged voices, aged voices. The recording quality gives greater prominence to the orchestra, which itself sounds coarse, below its recent best.

Eric Cutler, as the poet, has a more interesting presence here in modern dress than he did in operas such as from the Met, but Marthaler doesn’t mine it for anything. The tenor moves through much of the stage business in a good-natured but diffident way, as though giving his best shot at directorial ideas he has just heard about for the first time (you almost expect him to be glancing at pages in hand).

The villains have never seemed blander, less menacing, or more interchangeable than in the hands of Vito Priante. Ana Durlovski’s Olympia presents the doll as sad victim. “Olympia is broken!” means something else here; she walks off under her own steam.

Everything about the production bears the heavy stamp of a control freak, so it must be by design rather than by mutiny that Measha Brueggergosman, doubling Antonia and Giulietta, cuts through with a passionate operatic performance more remarkable for her committed acting than for her uneven singing. Her Giulietta seems a slatternly progression of her Antonia, suggesting the fate of an Antonia whose dreams were not realized. All three of the love interests are women as prisoners, but other directors have done more with this notion.

Anne Sofie von Otter, the Muse/Nicklausse, also is dashed on the rocks by the staging. Hoffmann’s friend seems aged, pinched, wan, in an unfortunate cloth hat that looks like something a well-off person with bad taste would choose only while undergoing chemotherapy. But on the musical level, von Otter alone provides sovereign artistry, twice, first in the higher-lying parts of the violin aria and then in the solo near the end consoling the fallen Hoffmann. The mezzo’s phrasing is of lapidary quality, but this is now a voice for the recital room and the recording studio. She was 58 and her marvelous instrument had not defied time; the will must pass for the deed in a long part’s lower third.

Maestro Sylvain Cambreling has had a long association with Les Contes d’Hoffmann, and he recorded the opera for EMI almost three decades ago. Here, he treats the score as one treats a nagging spouse after a long marriage, going along with its demands because this is the routine, and other options are unthinkable.

He and Marthaler have created a “new version,” the spine of which is the Oeser edition, with editing. For example, the prologue seamlessly leads into Spalanzani’s musings, with the orchestral introduction to the Olympia act omitted. The Giulietta act includes “Scintille, diamant” but not the spurious sextet, and Brueggergosman gets to sing “L’amour lui dit: la belle.” Whatever is performed, it is a sloppy, unedifying performance, frequently poorly coordinated, with duets and ensembles rarely properly unified. The wit and sparkle are gone from the music—sugary syrup rather than champagne.

The DVD runs 193 minutes, and often while watching it, I wished I were seeing a different production of Les contes d’Hoffmann, listening to a recording of Les contes d’Hoffmann, reading the stories of ETA Hoffmann, or listening to the piano playing of Josef Hofmann, or seeing a movie with Dustin Hoffman or Philip Seymour Hoffman, or holding out my hand and repeatedly performing the Hoffmann reflex test. To get through this once was an unpleasant task to be seen to completion. To return to it would be self-punitive.

Comments