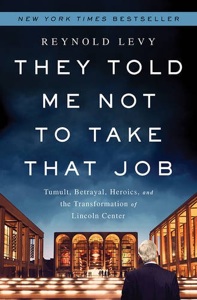

The redevelopment that took place at Lincoln Center during Reynold Levy’s tenure as president of Lincoln Center represents a considerable accomplishment. One can can question decisions, priorities and outcomes (devoting precious plaza real estate to a very good, but very expensive restaurant; the awkward, treacherous path from the Met through a Brian de Palma-inspired tunnel to the subway), but Levy deserves recognition for the combination of fundraising savvy, stubbornness, and leadership he displayed in getting this done. Surely, there’s an interesting saga to told. Unfortunately, Levy’s ponderously titled memoir

They Told Me Not to Take that Job: Tumult, Betrayal, Heroics, and the Transformation of Lincoln Center doesn’t tell it.

His recounting of the redevelopment itself is quite short on revealing detail on both the critical decisions that were made and the perspectives individuals involved. He sets the scene by quoting published articles describing the dysfunction at Lincoln Center rather than sharing his own observations. He and then follows with generalities such as “Parochialism prevailed. Lincoln Center was a quarrelsome, unpleasant place. Its leaders seemed tired, bereft of ideas, and lacking in energy” without any illuminating specifics or explaining whether he’s referring to the people who worked for Lincoln Center; the constituent organizations, or both.

Of those leaders, I certainly expected to learn much more about his challenges in dealing with Joe Volpe, the most vocal opponent to the redevelopment Volpe is described as volcanic, boorish, and generally ill-behaved, but we only get to the particulars of any of their disagreements in a didactic discussion of the reconfiguration of the shared parking garage at Lincoln Center. Levy does briefly discuss the economic hole that Volpe helped dig for the Met by raising ticket prices during the economic downturn, but overall his treatment of Volpe reads like an incompetently written performance review than a useful piece of history by a first-hand participant.

There’s more substance to be found in the chapter on the demise of New York City Opera. Levy traces the problems at the NYCO back to Paul Kellogg’s very public complaints about the State Theater as a performance venue and his search for a new home. Levy thinks that NYCO drove audiences away by pointing out the bad acoustics; Beverly Sills told him there was no problem with the acoustics, even if she might not be the most unbiased observer on this particular topic given the commonly-held belief that she burned out her voice singing punishing repertory in an acoustically challenging space. Any other musician he might have spoken to would have told him of the difficulties in performing there, particularly for the younger singers. Levy then admits later that the renovations that transformed the State Theater into the David H. Koch Theater greatly improved the acoustics.

By then, however, City Opera was pretty much doomed. Levy is justifiably unforgiving in pointing out the mistakes made by City Opera’s management and Board of Directors. He wrote a white paper for George Steele and Susan Baker providing his advice and an offer to help find new board members and cost savings. Apparently, George Steele never read the document and it outraged Susan Baker because she took it as an indictment of her leadership.

This doomed any further discussions between Lincoln Center and the City Opera. Is it a surprise they decided to leave? One wonders if Levy could have saved the NYCO by offering to help with emergency, anonymous fundraising amongst his board in exchange for NYCO agreeing to return to Lincoln Center in future seasons. We’ll never know.

Incidentally, he is just as critical of Anthony Tommasini’s very public support of City Opera’s noting “At almost every point of critical decision for the Opera, Tommasini’s advice was well intentioned but misguided, his track record unerringly wrong” and “ For years, Tommasini paid little attention to what it took to run a serious performing arts institution… His cheerleading for the New York City Opera to take on more elaborate and expensive programming in the face of its financial meltdown was quixotic.” But shouldn’t critics have a role in convincing a disillusioned public that City Opera was worth saving?

The failure of non-profit board of directors to provide proper oversight and stewardship is a common theme throughout at the book; He dissects the missteps at the NY Philharmonic and the Metropolitan Opera. Later, he devotes a chapter to pointing out the difficulties of running a non-profit and the lack of proper external oversight for foundations and non-profits.

One would expect, then, that Levy who has spent his career at foundations and non-profits would have some very strong ideas on how to improve their accountability and long-term viability. He raises the question without providing any useful answers. What is an audience to do when it sees a beloved institution fall into decline? He suggests that patrons can can “vote with their dollars and their feet.” as a way to spur reform. However, in the case of City Opera, by the time they reacted to their dire circumstances and appointed a new board president, it was well too late.

For examples of better leadership, he provides a chapter devoted to leaders who shaped his tenure at Lincoln Center including Beverly Sills, David H Koch, David Rubenstein (of The Carlyle Group), and Michael Bloomberg. The inclusion of Sills seems to be motivated by her lifelong devotion to Lincoln Center because the few anecdotes he tells about Sills elsewhere in the book are not very flattering.

He notes that her tenure as Lincoln Center Board president was “mired in controversy” and that she encouraged him to give in to union demands when he faced a strike by the Mostly Mozart Orchestra early in his tenure and “conjure up some face-saving language for management.” Alas, he doesn’t speculate on how her view on negotiating with unions informed her tenure as chairman of the Metropolitan Opera’s Board. As to David H Koch, Levy acknowledges that he is a controversial figure but thanks him very, very, very effusively for setting a new benchmark of $100 million for leadership gifts to performing arts institutions.

He ends the book with a lengthy chapter on leadership and it’s an insufferable barrage of platitudes. “In the ATM machine of leadership, asking for withdrawals will not be successful if you haven’t provided substantial deposits of time, attention, advice, and assistance “ is all too indicative of the content to be found here. Were there a non-fiction equivalent of the The Bulwer-Lytton Fiction Contest, this section would provide plenty of fodder.

Changing patterns of attendance and philanthropy coupled with the government’s complete abandonment of support for the arts will pose enormous challenges to nearly every performing arts non-profit over the coming decade. How can these organizations prepare for the coming turmoil? Levy knows enough to ask, but doesn’t provide any proposed solutions.

Comments