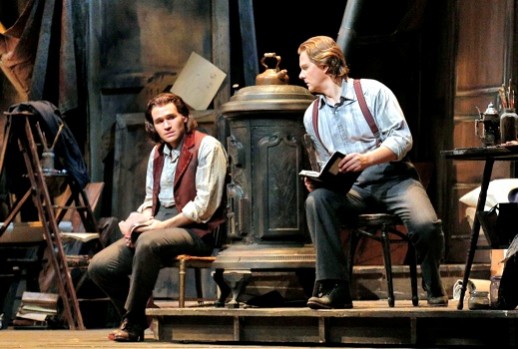

It’s true, though. I don’t know about you, but I usually spend the whole first act trying to remember which non-Rodolfo character is which. At worst, I resort to a protracted game of “Marry/Fuck/Kill.” This proved futile and unnecessary in present company, given the fine quartet of Bohemians put before us, their easy brohamnal chemistry, and, sure, their perhaps atypical attractiveness quotient.

John Caird is perhaps primarily a theater director, but one with a great deal of opera under his belt. His approach to Bohème is respectful of tradition, of the spit-take upon Benoit’s entrance and all that, but not lazy about its characters and their emotional lives. I am now going to overuse the word “ensemble,” but yes, he was fortunate to have his vision brought to fruition at various, appropriate levels of hamminess by such a vibrant ensemble. Let’s all say it with a really exaggerated French accent, shall we? ENSEMBLE! He was fortunate, too, in their overall vocal endowment, though in one particular it was a bumpy night.

Unfortunately something that may have been opening night nerves found her tone souring at the end of lines, her artistry writing checks her technique couldn’t cash. A number of arching phrases ended in decidedly non-diegetic sorrow. The first act ends, as we know, with an option for the fellow singing Rodolfo to sail to glory or take the gentleman’s option, come scritto. In this case, Michael Fabiano’s trip into the rafters was an act of gallantry; if he hadn’t sung the climactic C, it seemed nobody would have.

Still, Voulgaridou never withdrew from the character, and Act IV, with fewer purely musical hurdles to jump, was an unflaggingly effective ensemble effort, both as music and drama, reducing this critic at times to rubble. Weary as I am of scrambling for superlatives to lob at Christian van Horn, his serenade to outerwear was the tragedy’s beating heart, delivered with simplicity and poetry. (I’ll confess for a moment, when he began the piece with the coat draped over a chair, I found myself uncomfortably back at the Republican National Convention.)

Well, you must know why I went to this at all, other than I’m a Big Fancy Critic now. It was to hear Fabiano, the most promising young tenor we have, though really now the promise is fulfilled. Fishing around for the right superlatives to describe his singing, one is drawn to old-fashioned descriptors. Verily his singing is splendid, the kind of thing (not to minimize the hard work he doubtless has done) you can’t pick up at conservatory and really don’t even learn through experience. It’s there or it isn’t, and in his case, it’s all over the place. The sound is youthful but rock solid. The phrasing might be described as immaculate if it weren’t also spontaneous. Fabiano’s Rodolfo now goes on that list, next to things like Deborah Voigt’s Chrysothemis, of roles I do not expect ever to hear sung better.

Nadine Sierra was a just-right Musetta, a little chirpy in tone but not in a bad way (we do still like variety in voices, don’t we?) She and Caird found a happy compromise between the harridan she sometimes gets portrayed as and the drag parody directors sometimes ask for instead–I still recall a college friend who archly said at a voice department recital featuring the whole lapdance routine “She’s a vamp, not a stripper. It isn’t quando m’en blow.”

Indeed, if you are playing with Schaunard’s hair a little, you’re probably fine. If you’re playing with his g-spot, you’re in the wrong opera. In any case, she didn’t camp it up enough for the last act’s redemption to ring hollow or cheap, though one did wonder for a moment if certain gestures were Kardashianesque.

You know, it’s possible to listen even a beloved work into sonic wallpaper, to chew all the flavor out of it. I first listened to La Bohème when I was sixteen, on records from the public library, and it’s lived with me in various ways, through “Verdi is better than Puccini” phases and “Puccini is better than Verdi” phases. For a while I would try only to listen to it on the first cold night of a year to see if I could find fresh ears for it again. To this fine ensemble (with a quick box on the ears to the San Francisco opera for not pairing Fabiano with the lovely Leah Crocetto on any evening) I am grateful for bringing Bohème back to me.

Photos: Cory Weaver/San Francisco Opera

Comments