To some, Anne Schwanewilms will always be the soprano in the slinky black dress who replaced Deborah Voigt at Covent Garden a decade ago and confirmed the creeping influence of film and television values on the opera world.

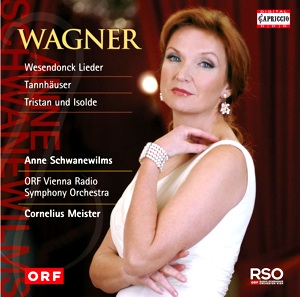

Though she’s since secured a place as a leading interpreter of Richard Strauss’ operatic heroines, the German soprano’s forays into Wagner have been limited to a handful of Tannhäusers and Lohengrins. A release on Capriccio with the ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra cautiously stakes out more turf with performances of the Wesendonck Lieder and Liebestod from Tristan und Isolde, along with Elisabeth’s “Dich, teure Halle” from Tannhäuser. It’s a somewhat ungenerous vocal sampler, with more than half of the disc devoted to orchestral excerpts led by your choice of Cornelius Meister or Manuel Lange, both of whom are credited as the conductor.

There’s a cool gracefulness to Schwanewilms’ voice that matches her elegant stage presence. The intonation is precise and the vibrato razor-thin. In hushed passages, she has an effective soft attack that’s capable of expanding into a glowing crescendo. The top is more piercing and sometimes leaves the impression of sounding a tad strained. Overall, the concentrated tone and regal mien can leave you convinced you’re hearing an echt rendition of a lied or operatic excerpt.

The problem is one doesn’t always sense a strong identification with the material, as if the soprano is trying to channel emotional power through her restraint. The wonderfully surging opening of “Schmerzen,” the fourth of the pathos-filled Wesendonck songs, sounds rather by the numbers, with neither a blazing entry or much deep-rooted feeling in the opening line “Sonne, weinest jeden Abend.”

Similarly, the Tristan study “Träume,” for all its gentle intimacy, fails to convey a yearning for eternal rest embodied in the final phrases about dreams softly fading and sinking into their grave. It’s possible Schwanewilms would make more of an impression singing this set to the piano accompaniment, though the Vienna radio orchestra brings out the beguiling tonalities effectively without distracting from the vocalism.

The Liebestod fares better thanks to Schwanewilms’ clean upward attacks, graceful phrasing and warm middle register. This is an Isolde who’s more feminine and vulnerable than angry. There’s a sense of freedom in the intensifying expressions of passion and in the final octave leap between F-sharps. The performance may lack the depth and power of a Nina Stemme or the urgency of Anja Kampe but has a certain unwavering focus appropriate for a character embarking on a journey to another realm.

“Dich teure Halle” is the best fit for Schwanewilms on the disc — an ardent lyric essay that’s tastefully shaped and redolent of an early Romantic style that has direct connections to Weber. If only the producers saw fit to give us some more from this opera, perhaps Elisabeth’s Act 3 prayer “Allmacht’ge Jungfrau, hor mein Flehen!”

The orchestral excerpts tend to be fleet, fashionably lean and unremarkable. The Tristan prelude is competently played but fails to quite capture the long dramatic arc Wagner etches to expose the tormented title characters’ lives. The Venusberg music from Tannhäuser doesn’t throw off nearly enough frenzied emotion to qualify as orgiastic, though there’s some commendable articulation of detail. The approach generally seems influenced by Pierre Boulez’s pared-back Wagner, with sound that at time resembles chamber orchestra proportions.

Schwanewilms has won over big segments of the operagoing public since bursting out under unusual circumstances. While she may be a go-to Straussian and excel in Romantic art songs, this disc probably does more to delineate the limits of her artistry than enhance it.

Comments