It may have taken most of Verdi’s canon to do it, but the “Tutto Verdi” collection finally manages to do justice to Verdi in his last two operas, though they cheated with the Otello, which is from the 2008 Salzburg Festival rather than from the smaller Italian houses where the rest of the performances in the collection are from.

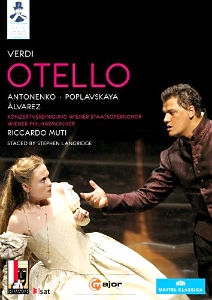

Needless to say, the Otello is first-rate. Riccardo Muti leads a polished, high-octane performance from the starry, youthful cast and the Vienna Philharmonic in the pit. Interesting, even revelatory details of the score–articulations, harmonies, inner lines etc.–arise from his immaculate approach to the music (even more so when heard live) but there is admittedly a feeling of efficiency and calculation that may not be to everyone’s taste, yet is not exactly incongruous to late Verdi. The cast, headlined by Aleksandrs Antonenko and Marina Poplavskaya in their role debuts as Otello and Desdemona, fits well into Muti’s approach to the score.

In the title role, the baby-faced Antonenko sings with an astonishing ease and power that bodes well for his future in the part. What hopefully will develop is a more dramatically nuanced and complex conception of the role. Vocally, his performance is superlative, but he still has a ways to go in exploring the possibilities of this iconic part. Here, his Otello has a limited range of emotion and too often it seems as if he lacks dramatic conviction, even in the love duet where not even the hyper-alert acting of his Desdemona seems to inspire him. There is no vulnerability or tenderness in his acting, nor does he convey torment or struggle in his singing as those with a more jagged vocal production naturally do.

His dramatic deficiencies are made unusually obvious by the gripping performance of his Desdemona, Marina Poplavskaya. I have never fully enjoyed a performance by this divisive artist, but here perhaps due to the relative ease of the role, hers is the most committed and complete performance of the cast. The live audience seems to agree and gives her the biggest round of applause during the curtain calls. In addition to beautiful singing throughout, her acting is credible and specific, portraying Desdemona with a convincing child-like naivete that is never coy or affected. This conception of the role sorts out the dramatically problematic nature of the character and makes her terror at Otello’s outbursts all the more moving.

Carlos Alvarez‘s suave and sinister acting are well-matched by his dark voice, even if he does not have quite enough of it to make his Iago truly terrifying. This Iago is purposeful and desperate rather than pure evil. In the supporting parts Stephen Costello‘s sweet-voiced Cassio is a standout, his unique timbre distinctive even in such illustrious company. Last and very much least is the production, directed by Stephen Langridge. Apart from his presumed work with the three principals, it is quite frankly, a mess. There are too many failed attempts at symbolism and half-baked gimmicks substituting for insight, and the production is best ignored in favor of the excellent performances by the singers and the orchestra.

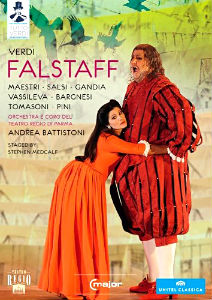

Rounding out the collection is Falstaff from the Teatro Regio di Parma. This is not the wittiest or most sparkling Falstaff on video

, but it is perfectly respectable. In many ways, it showcases the best that a smaller house can offer: a well-rehearsed and directed ensemble cast, charming budget production, and feeling of fun from the performers.

In the title role, Ambrogio Maestri possesses the highest-caliber voice of the cast, and dominates the opera with his imposing presence. That there is a menace to his portrayal of Falstaff renders the comedy more vivid. Overall though, his characterization is a bit too generalized, and he doesn’t achieve the charming idiosyncrasy that Christopher Purves does in the DVD of Richard Jones‘s production from Glyndbourne.

Vocally, the men fare better than the women, who while more characterful are also often shrill and wobbly. As Alice Ford, Svetlana Vassileva seems like somthing of an odd choice, with vocal qualities suited to more dramatic parts. Yet despite her edgy tone, Vassileva is surprisingly satisfying and inhabits this mischievous role with vivaciousness and charm. The rest of the women are variable, with Daniela Pini‘s Meg Page rather anonymous, the Nannetta of Barbara Bargnesi sweet-acting but not so sweet of voice, and Romina Tomasoni a lovable, jovial Mistress Quickly with a warm, sunny contralto to match.

Luca Salsi‘s suave, compact baritone is stretched by Ford’s brash outbursts of jealousy, but otherwise fits this aristocratic part well. Antonio Gandia‘s sweet tenor and graceful phrasing suit Fenton beautifully and his singing is a highlight in his interludes of young love with Nanetta. The traditional production by Stephen Medcalf cleverly utilizes rather modest resources, making use of basic props and lighting to set the stage for the action. More variety in the color palette, though, could have made the staging seem a bit less drab and low-budget. The orchestral playing is crisp and jaunty, and the very young conductor Andrea Battistoni does an admirable job of untangling the musical lines and keeping things cohesive.

Comments