Taneev was quite a high-minded fellow, so it’s not altogether surprising that nothing less than Aeschylus (and the whole of his Oresteia!) would suffice as a libretto for his first and only opera. Despite the antique theme, I think the subject would have resonated profoundly with contemporary Russian culture. Taneev’s Oresteia might be considered a sort of meditation on the themes of regicide and redemption.

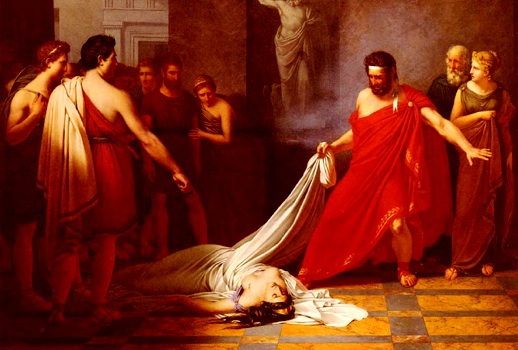

As a bit of historical backdrop, recall that Tsar Alexander II was assassinated by an revolutionary’s bomb in 1881. Taneev first began work on the opera in 1882. To summarize the plot: In the first act, Aegisthus and Clytemnestra engage in a palace conspiracy, Cassandra prophesies woe for the people, and Agamemnon is murdered. In the second act, Clytemnestra isn’t sleeping well and the people are woeful. Orest returns, avenges the regicide, and fully expects to be rewarded for his acts. To his surprise, he is instead punished with the hellish furies. Only through the intervention of Apollo in the third act is he freed from living damnation.

In this opera, power is inescapably bound up with violence, and the question it poses is: Is there any way to have a morally pure ruler? The answer which the opera seems to offer is “yes, by the grace of God”. The last act, depicting Orest’s liberation from the persecuting Furies, contains some of the opera’s most beautiful music (and perhaps it foreshadows Rimsky’s Kitezh or the end of Scriabin’s First). Taneev’s sacro-melioristic (to coin a term) Oresteia, where an inescapable cycle of violence is broken through divine intervention, might be seen as a response to the pessimism and cynicism of the time, clearly expressed in works like Musorgsky’s Boris Godunov.

However, I think this opera will present a couple of big musical challenges to the Bard audience.

One has to do with Taneev’s very particular style. He is not showy. He is a composer for musicians. He is extremely scrupulous in not writing a note more than he needs to. Textures tend to be on the thin side. But each line is contrapuntally active: there seldom is a lot of gaudy “filling out” of harmonies. Octave doublings are only used when necessary. (One interesting consequence of this style of writing is that Taneev sometimes develops his own form of Klangfarbenmelodie, where a single melodic line changes orchestral timbre mid-span.).

In terms of musical syntax, Taneev is very much a “constructing” and “developing” composer. It is not for nothing that he is sometimes compared with Brahms. An initial musical idea might seem unpromising, but it is soon embedded in a web of modulations, subtle counterpoint and motivic development. Though the key scheme of Oresteia is complex and varied, it never feels forced. It often requires some concentration for the listener to fully realize how much Taneev is accomplishing with his restrained means. His mastery is of the quiet sort—he is the anti-Prokofiev.

But the Oresteia will lack some elements which audiences might expect from a Russian composer. Despite his Chaikovskian background, there are few hummable tunes in the opera. There is melody, worked out in a somewhat symphonic manner, but—a couple of Leit-tunes aside (more below)—little to whistle on the train home. There are also no “Russianisms” of the St. Petersburg school. Taneev’s orchestration is not nearly so luxurious as Rimsky-Korsakov’s or Glazunov’s; rather it sounds like orchestration written in service of the musical idea. I think Taneev’s ideas are good, so for me it’s not a problem. Others might find it wan or insipid.

I think the biggest stmbling block for the audience could be the form of the opera. Each act builds to a satisfying climax. But to achieve that effect, Taneev avoids placing big climaxes and highly rhetorical conclusions in the middle of each act. Even big duets end in surprisingly innocuous ways. Arias seem to finish a minute or two too soon. The individual sections of the opera often feel too short.

In fact, the musical flow is often reminiscent of one of Gluck’s reform operas, where short contrasting sections are strung together to capture the momentary twists and turns of the plot. This poses a dramatic and musical challenge to the performers: maintaining tension through all the pauses and perfect cadences. I think this slight awkwardness in style is less a sign of Taneev’s compositional incompetence than a reflection of his search for a noble and epic theatrical experience. But it’s a characteristic of the opera which is particularly prominent in the first act, and I fear some audience members might not stick it out.

On the other hand, Cassandra’s atmospheric, visionary monologue in Act I might persuade them to come back after intermission. It has one attention-grabbing musical moment with a melody over a descending bass tetrachord, the traditional 17th-century emblem of lament. Indeed, it sounds quite a bit like Dido’s “When I am laid.” This tune will reappear in the second act when Orest is about to slay his mother; the quotation from Cassandra’s monologue reminds the audience of her prophecy.

There are other nice set pieces in the opera. Aegisthus has a passionate monologue explaining the source of his hatred for Agamemnon. Elektra shares a couple relatively high-flying duets with her mother and her brother. The choruses are enlivened with many contrapuntal details.

As a whole, the opera develops a bit like a late 19th-century, “cyclic” symphony. There are hints of a “redemption theme” (easily identifiable by their turn to a bright key like C major and their relative tunefulness) in acts one and two, but they only are fully developed in the third act—when Apollo declares Orest redeemed. The opera is filled with other, more subtle leitmotives that might not be fully apparent at first hearing. It’s a work which repays attentive listening throughout its three hours.

The Oresteia is an early work for Taneev, and it was an unusually difficult piece for him to complete to his satisfaction. He labored on it for twelve years. For those who would like to hear mature Taneev in outstanding performances, I can’t recommend strongly enough the recordings of his chamber music made by the Taneyev quartet in the late 70s. The Taneyev Quartet didn’t have the benefit of modern sound editing, but they pull off a lot of hair-raisingly difficult passages with tremendous aplomb. Their performances are carefully thought out and warmly romantic.

Bard Summerscape presents Oresteia, “the first time this towering work has been staged in its entirety outside of Russia since its premiere at the Mariinsky Theatre in 1895,” July 26-August 4.

Latest on Parterre

parterre in your box?

Get our free weekly newsletter delivered to your email.

Comments