When I acquire DVDs of opera performances, I look for performances which truly merit a video recording; performances in which the totality of the musical and dramatic elements are worth preserving for repeated viewing. These three DVDs of Verdi’s middle operas from the Tutto Verdi collection all fail to satisfy this requirement, though by differing margins. And to tell the truth, none of these performances are second or even third choices for DVDs of these operas.

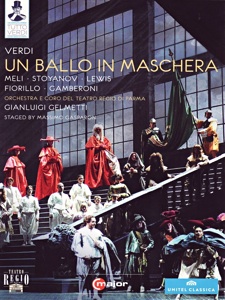

The least satisfactory performance comes first, Un Ballo in Maschera, recorded at the Teatro Regio di Parma. Overall this performance has the qualities of a bad revival: lack of direction, uneven casting, and lackluster orchestral playing. The production, with costumes and sets by Pierluigi Samaritani is drab and traditional, and his costumes flatter no one.

The stage director for this revival, Massimio Gasparon, seems to have just directed traffic, leaving the specifics of characterization and acting to the principals. Needless to say, it is not cohesive nor specific, never mind trying to make sense of this tricky drama.

Our Riccardo, Francesco Meli, sings stylishly but his bright, monotone voice lacks variety and the top tends to become tight and dry when pressed. He is not a very involved actor and it is obvious that he is often thinking about his singing. In contrast, Kristin Lewis‘s Amelia is well-acted and sympathetic, but sung with a glaring, stressed top and unsteady middle that becomes breathless and underpowered as she moves towards the bottom. The voice occasionally is beautiful when she isn’t forcing it, but its deficiencies significantly prevent her from making expressive points.

The most compromised voice in the cast though is undoubtedly the Ulrica’s, Elisabetta Fiorillo, whose voice is tremulous and wobbly from top to bottom. The writhing women in her scene are a campy distraction, but no substitution for quality.

For that we look to Vladimir Stoyanov‘s Renato, which is the best-sung performance of the cast. The highlight is a deeply-felt “Eri tu”, which receives the longest ovation of the evening that he even breaks character to acknowledge. It is still not an ideal performance, since his smooth, elegant singing becomes dull in dramatic declamation, mirrored by his relatively mild characterization. These are minor quibbles though in this company.

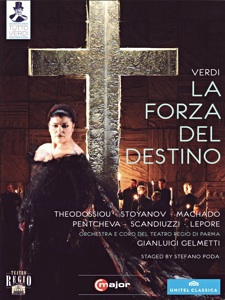

The same house is responsible for the next performance in this series, La Forza del Destino, which is presented

note-complete. From the outset things seem to be off to a better start. The slackness and sloppiness of the orchestra in Ballo have thankfully been replaced with energy and incisiveness. The conductor for both operas is Gianluigi Gelmetti. The production by Stefano Poda is also an improvement, if a qualified one.

The sets are abstract with traditional props and costumes. Distracting stylized stage movements and choreography are assigned to non-singing extras who also serve to move the large, domino-like black and gray edifices which dominate the set and can be configured into various shapes creating, for example, a giant cross in the monastery scene. The lighting is beautifully done and creates some striking stage pictures. None of this has much significance, though, since the direction of the principals and their relation with the rest of the production are squarely traditional. The direction is at least clear though and the characters do not seem to be fending for themselves.

Dimitra Theodossiou, who is made to wear a series of ugly costumes, the worst being a strapless black gown that can only be described as avian-chic, is our Leonora di Vargas. Perhaps more unfortunate is her wobble, which is worthy of the comment Walter Legge allegedly made to another Greek soprano during her recording of this opera. Sadly she does not possess the strong lower register of her countrywoman, and many passages which are meant to convey the strength and gravitas of the character fall flat. This is for me rather unforgivable in this part and coupled with the aforementioned wobble and painfully wiry top, I find that no level of commitment on her part can compensate.

Things are not much better with Aquiles Machado‘s Don Alvaro, whose whiny top had me running to turn down the volume more than a few times. The middle and bottom are thankfully more pleasant. Again, in such company Stoyanov is the best singer on stage, a balm for the ears. He sings Don Carlo di Vargas with beauty and refinement throughout, the voice less dull than in Ballo. As in that performance, however, his voice is just too soft-grained to deliver much of a punch when the drama calls for it.

Roberto Scandiuzzi‘s woolly and wobbly voice, choppy phrasing, and spotty intonation make for a Padre Guardiano that is anything but the rock that he should be. The Preziosilla of Mariana Pentcheva is (as she so often is these days) an ungainly, wobbly Slavic mezzo with an iffy top that makes her scenes seem to drag on longer than they already do. She deserves our pity though since she is the only principal singer who is made to partake in the strange, jerky choreography of the extras.

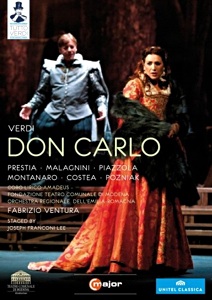

After these two dispiriting performances, I was not expecting much from Teatro Comunale di Modena’s Don Carlo. To my surprise, this ended up being the most satisfying

performance, musically, of these three. It is given in the five-act “Modena” version, very similar to what we’ve heard at the Met in recent seasons.

The budget production, by Joseph Franconi Lee, is traditional and utilizes a unit set comprising of wooden platforms, risers, and stairs somewhat resembling the backstage of a theater. In a different setting I would guess this symbolizes the public-private dichotomy, but the generalized direction does not give any indication that this is the case. In truth, a bare stage with props would have been just as effective if not more, considering the unattractive set does not serve much purpose other than to occasionally trip-up the singers.

The most interesting singer in any of these three operas is Cellia Costea, the Elisabetta di Valois. Costea has a distinctive, dark-hued voice with an uncanny resemblance to her countrywoman Angela Gheorghiu‘s, especially in the black-satin middle and bottom. The top can retain a soft, rounded quality or become more dramatic and cutting when necessary. She is the only performer here who seems to understand and convey the scale of the drama through both her committed, sympathetic acting and noble, sensitive singing. And as icing on the cake, she ends the opera with a secure, blazing high B.

The rest of the singers are not at this level, but are solid enough. Mario Malagnini as Don Carlo has a substantial, distinctly Italian tenor sound that is quite beautiful and secure, but he has little chemistry with any of the other performers. His acting is generalized and disconnected from his singing, and he glances at the conductor a bit too often. The Rodrigo, Simone PIazzola, has a solid if faceless voice that is equal to the part, but it is delivered in a plain and obvious way that is at odds with this complex, ambiguous character.

As Filippo II, Giacomo Prestia has all the right intentions but his voice is too wobbly and worn, fading into the background until Act 4 where he sings a sympathetic and fragile “Ella giammai m’amo!”. He is a convincing actor and gives a menacing, yet vulnerable account of the king. Luciano Montanaro‘s Inquisitore conversely sounds a bit too healthy, a rich true basso that unfortunately loses color at the top when pushed.

Alla Pozniak as Eboli has an engaged and alert stage presence and offers a big, fruity Slavic voice with plenty of chest and predictably cloudy diction. The top, however, goes off the rails in a quivering, exciting Waltraud Meier-esque way, but is too often unacceptably disconnected and out of tune, most egregiously in “O don fatale”. Fabrizio Ventura‘s conducting is square, lacking shape and momentum. The orchestra plays well but without brilliance.

In summary, with the exception of Costea’s Elisabetta, none of the performances in these three operas are those which I will be returning to. All of these operas are better served on video elsewhere. My top picks for filmed versions would be David Alden‘s Ballo (floating around the YouTubes somewhere), the Tebaldi or Caballe Forzas, and Pappano’s Don Carlos or either of Levine’s Don Carlo performances.

Comments