In Parsifal, a sacred order of high ideals has gone off the tracks and must find a way to renew itself in order to continue to function. Or are its ideals not so very high? Are its basic premises false? Not everything in Wagner is what it seems, and not all implications are clear. Is this sacred order Christian, and how closely is the “redemption” sought by the main characters a dogmatically Christian one? Or was Wagner merely making use of the Christian religiosity of his times (and of his medieval source) to devise an existential legend of his own, owing not a little to Schopenhauer and to Buddhism?

And how greatly did his dabbling with crackpot racial theories, religious theories, political theories, psychological theories, even vegetarianism influence the working out of that myth on the stage and in the score? Nothing is ever simple in Wagner’s world. That is why he provided simpletons and fools to guide us into it and discover it (Siegmund, Siegfried, Elsa, Walther and Parsifal, the “pure fool”). We share their bewilderment; perhaps we can share their enlightenment—at least, Parsifal attains enlightenment.

At the core is a music-drama not quite like any other, music of ever-renewing beauty, fifty years of Wagner’s experience with operatic composition distilled and matchlessly potent. In ages past, the Met used to present Parsifal once a season, on Good Friday, but its congruence with any other faith’s celebration of spring and rebirth has never been exact. A good Parsifal is its own rite of passage.

That the Met forces can play it and sing it is almost a given; performances of Parsifal of supreme quality have been a company staple for decades. On the evidence of the new production, at last Monday’s performance, they can also stage it, produce it and cast it in a way that overwhelms all doubt and sets out a particular form of its basic conflict, of the error of society that must be answered, that can perhaps be corrected.

François Girard’s fascinating new production, originally designed for the Lyon Opera, focuses on the War Between Men and Women. In Act I, the nearly bare stage is divided into unequal sectors by a curving hump of earth (Yin and Yang perhaps?), with, occasionally, a brook flowing in the divider. The sexes do not cross that line. A non-singing women’s “chorus” in black veils fills half the stage, crowding into a knot, circling wordlessly, sitting in isolated meditation. The Knights of the Grail, in formal attire at curtain’s rise, remove their jackets and ties and sit in chairs in two concentric circles, forming a “temple” in the magical sense. They remain in their shirtsleeves and are also barefoot: an “informal” club, and a boys’ club at that. No dames allowed.

Kundry (Katarina Dalayman, with a full, womanly sound and very little of the pitch drift that sometimes marred her Brünnhildes) staggers in from the women’s side and hands her Arabian balsam across the divide to the anguished, debilitated, wounded King Amfortas (Peter Mattei—is he the greatest singer alive or the greatest actor? Can’t make up my mind). An angelic emissary from the women’s side brings in the wounded swan, but Parsifal (Jonas Kaufmann, in a trenchcoat and—gasp!—shoes), though plainly an outsider, keeps to the proper side of the gender boundary.

The pure fool is a rube, ignorant of society and of his own name. He studies Amfortas’s curious behavior with the Grail at the altar, a look of dim bewilderment on his face. (“I’m not in this opera; I just wandered in off the street. In shoes.”) The voice of Gurnemanz (René Pape, never more warmly, serenely mellifluous) turns gruff with disappointment as he kicks the thoughtless lad out of conclave for raising and disappointing his hopes. An interesting touch (among so many): The Knights pass the sacraments on, one set to the next, with (it looked like) wafers of the Mass, but though they did this piously, it was without making the sign of the cross. This is clearly a sacrament, but the religion is not specific—any all-male cultic group might be on display.

At the conclusion of the act, the hump dividing the two sexes glowed red and the two sectors of the stage began to pull apart. Smoke rose from the crevasse. Parsifal, alone on stage, fascinated, drew close to peer into it. His next step was perfectly clear.

Act II opened within this hellish ravine, its cliff-like walls rising to imponderable heights with, at the rear of the stage, a very thin cleft seeming to lead to a molten corridor, useful for entrances and exits and (it seemed to me) full of sexual symbolism. The triangular stage was filled with a dark pool of red liquid. Front and center, in a dark suit and a crimson waistcoat, Klingsor (Evgeniy Nikitin, visually and vocally imposing), surrounded by Amazons in symmetrical array with long black hair, like the crew of some alien starship or the female counterpart of the male cult in Act I.

They are all standing in the red pool—except Kundry, who lies semi-conscious on a lip of the stage. The pool may represent menstrual blood, a source of our continued existence, remember, but one that occupies a highly magical place in folklore. In some cultures, women are said to feed their blood to men whom they wish to bewitch—or so say those men who fear the witchcraft of the women they oppress.

But this pool of blood also recalls two unhealing wounds: that of Amfortas, who sought to unite male with female sexually, and that of Klingsor himself, who sought to anneal his sexual urges by self-castration. We are now in Klingsor’s bloody kingdom, where everyone is female (or perhaps a female phantom), aside from Klingsor himself, a self-made man or rather, non-man: a eunuch.

The boundaries between the genders are not in effect here, and the women, instead of being discreetly veiled, carry spears, artificial phalloi. So does Klingsor, but his spear is the Holy Spear, stolen from the Knights of the Grail. The two wounds that Spear has made are the one in the side of the crucified Savior and the one in the groin of the sinning Amfortas. (His side, actually, in this discreet staging.)

Enter Parsifal, still in shoes, wading into the sexual heat of this exotic realm. The Flower Maidens sing him their yearning, fragrant melody, and the simpleton becomes dizzy, intoxicated, confused. He staggers into their arms. But a woman in white summons him: “Parsifal,” the name he has forgotten, amid the bewildering scents he has forgotten, perhaps because it is the scent of his mother, the only woman to whom he had ever before been close. (Kaufmann seems stoned, entranced; his attractive baritonal voice rising by startling degrees to striking tenorial self-knowledge.) The woman in white, Kundry, sings of his long-dead father, his recently dead mother, of their yearning and their pain, of the carnal knowledge that produced their son.

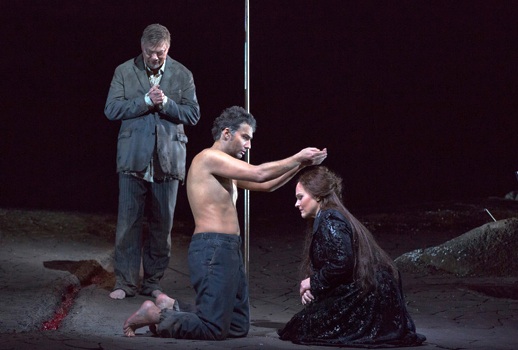

Suddenly there is a bed of pure white sheets. Parsifal falls back across it, shirtless, stunned and bewildered. In the smoky air behind Kundry, Klingsor appears to gloat. Kundry gives the boy a delicate kiss. He kisses her more passionately, but his hunger is not lust; it is for another sort of knowledge. Through the kiss, Parsifal understands her yearning for oblivion and the feelings of the last man who kissed Kundry… Amfortas. In allowing himself to lust for the distraction of sex, Amfortas missed the chance to unite male and female in a spiritual consciousness.

Parsifal rejects Kundry’s entreaties to join her on the bed, and her intemperate desires emerge as bloodstains on its sheets. They are soaked in blood by the time Klingsor emerges from the expanded cleft in the ravine, the Spear in his hand. But Parsifal is too strong now for Klingsor’s magic; through understanding and pitying Amfortas, he has been able to resist Kundry, even to resist his pity for her desperation. He seizes the weapon and makes the sign of the cross. The Mage and his Maidens sink drowning into the pool of blood. (Were they real or an illusion of Klingsor’s?) Parsifal, still in his wet shoes, marches out.

In Act III, we find the kingdom of the Grail, fallen on hard times. There are bomb craters. The chairs of the circle lie about in heaps, as do the Knights and the women, the two groups still unable to console each other, still divided by the glowing stream running through the stage. Gurnemanz, in a shabby jacket and torn trousers, finds Kundry and wakes her, reaching across the stream to jostle her out of her bad dreams.

Symbols of space and stars fill the screen behind the stage and a Spear rises over it, borne by a cloaked tramp. It’s Parsifal, all right! But a Parsifal visibly changed. Where has our curly Kaufmann gone? He’s got a crewcut! And it’s gray! He’s aged twenty years since Act II! Carrying this Spear is plainly no picnic. (Wagner does not specify how much time has passed between Acts II and III.)

Gurnemanz procures a flask of spring water to anoint the new king. Not till the moment of Kundry’s baptism does Parsifal gently pull her across the stream. She is redeemed and the bitter war between genders that goes back millennia, longer even than Kundry’s accursed existence, resolves in a new unity. A luminous convexity fills the sky to become the equinoctial full moon that heralds Good Friday. The assembled folk, male and female still divided, unenlightened, appear for the funeral of Titurel (Rúni Brattaberg).

Their utter demoralization in this featureless, storm-clouded landscape for once seems proper for their bitter and ungenerous attack on desperate, pain-wracked Amfortas. I’ve always felt, at that point, that the Knights of the Grail, for all their supposed sanctity, sure don’t demonstrate much Christian (or basic) generosity towards a fellow Knight’s suffering—but that may have been exactly Wagner’s point: Dogma without the personal attainment of compassion is never enough. It’s tough to out-think someone who thought as elaborately as Wagner.

And then our party of three enter the meeting, Parsifal, Gurnemanz with the Spear—and Kundry carrying the altar of the Grail. And it is she, acting the priestess, who opens the chest and elevates the Cup. This will not please those (like the recent Pope) who feel that women should not take on the duties of priesthood. Is this heresy, which is not found in the libretto, intentional on Mr. Girard’s part? Oh, I think it must be.

Into the Cup that she holds, Parsifal, having cured Amfortas’s wound, places the point of the Spear. The male symbol meets the female symbol, as in the womb, seat of all fertility. It is a solemn, a joyous moment. Amfortas seems as touched and awed as he is relieved of his hideous burden. And as anointing joy seems to descend in a mote of light through the clouds, Kundry falls into her only desire, the sleep of death. The concluding image was so perfect even the Met audience was very nearly silent while the curtain fell.

Daniele Gatti, veteran of some seasons of Bayreuth Parsifals, led a loving, thrilling performance, crackling with drama even in its pauses, carefully linked to the acting choices of the singers. Orchestra and chorus acquitted themselves nobly. The video program of Peter Flaherty was generally subtle and did not (as these things so often do) distract us from the figures performing the opera.

This is a cast that makes me eager to attend another performance of the run: Kaufmann’s confused witnessing turning into an ardent, determined undertaking of the heroic burden; Dalayman’s lyrical rather than eldritch Kundry; Mattei’s ease in filling the house with sound as meaningful as beautiful; Pape’s inexhaustibly serene Gurnemanz. I’d also like to attend an HD broadcast to see their acting up close, but full marks must also go to Girard’s fascinating production. I hope it returns to us often, with the spring in its saddlebags. Like the life-giving Grail, art on this level sustains us in our quest.

Photos: Ken Howard, Metropolitan Opera

Comments