Following an assassination attempt on the life of Napoleon III by three Italians in 1858, the censors in Naples (where the opera was originally to premiere) demanded drastic changes to the setting of the opera as the political climate in Europe was not conducive to depicting a monarch being killed onstage.

After withdrawing from the commission with the Teatro San Carlo over their demanded revisions, Verdi took his opera and headed to Rome before finally acquiescing into changing the main characters’ names and moving his story to colonial Boston. It was common practice to set the opera there until the past half century.

Despite all of the initial controversy, the plot of Ballo seems relatively anodyne. In typical operatic fashion, the assassin becomes the King’s best friend and the murder is spurred on by a love triangle. There is little commentary on the nature of Gustav/Riccardo’s rule in the libretto other than Count Ribbing and Count Horn making vague references to those who have died because of the King.

His subjects seem to adore him and they even mourn over his death during the opera denouement. He asks for forgiveness from his best friend turned betrayer as he dies and is given it. It is conflicts created by the midnight tryst that comprise the core emotional content of the opera, not the political commentary.

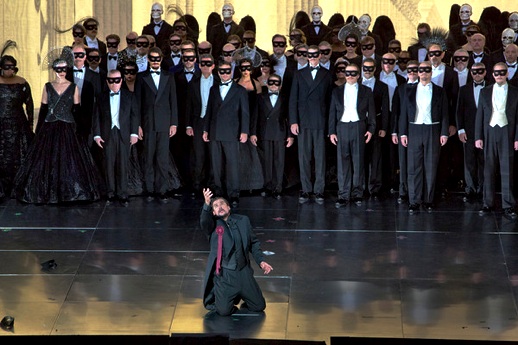

A large painting of Icarus falling from the sky adorned the stage, and if you read the program notes Alden goes on about how Gustavus is similar to Icarus in that they want to have it all and end up getting too big for their britches. Ok. But would anyone have made that connection as a result of the way the story was presented instead of it being plastered all over the stage?

At the ball guests, were wearing black wings, and an Icarus cutout even descended from the rafters in case we missed the enormous painting of him. Is the connection far fetched? Maybe not. But a painting on stage does not a story make. It may as well have been any other painting, with any other uninsightful blurb to explain its function.

In the program notes Alden says that Paul Steinberg‘s spacious sets and Brigitte Reiffenstuel‘s costumes were meant to create a “very correct Swedish court” from the early 20th century, but then Alden mentioned that the production was intended to be “dreamlike.” Apparently, that’s why Gustavus spent a fair part of the evening in an armchair downstage overlooking what’s happening. But the other characters speak to him while he is in the armchair. His sitting in it never removed him from the action or interaction with other characters.

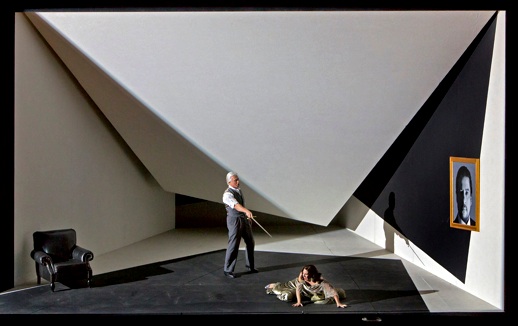

The one effective scene of the entire evening was Act III scene I in Anckarström’s study. Indeed, it was the only time all night that the evocation of film noir that Alden mentioned in the the Met’s promotional videos seemed appropriate. The set was a smallish rectangle that was empty save for a chair and a painting of Gustavus. It employed the chiaroscuro lighting made famous during the classical film noir period of the 40s and 50s. As we watched Anckarström succumb to his sinister nature, the backdrop of the set went black in small segments.

But more importantly, the scene’s melodrama could have come straight from The Maltese Falcon. Sondra Radvanovsky used her sexuality and the memory of their child to convince her husband not to send her on a swimming trip with the fishes. Think “I’m over the moon for ya Johnny, honest!” In a particularly affecting moment during “Morrò ma prima in grazia” (Amelia’s plea to see her son one last time), she sings the last phrases to the painting illuminating the guilt she feels for still loving the king despite what it has done to her family.

The musical aspects of the show found precious few delights as well. Fabio Luisi‘s conducting was generally bloodless, and there were quite a few moments in which the singers were not in sync with the pit. But generally the orchestra was as it usually is under him; unobtrusive but also uninspiring.

Marcelo Alvarez proved to be woefully inadequate in the role of the doomed monarch. His phrasing was as dull as dishwater, the top of the voice was forced and dry, but worse the role seemed largely uncharacterized. When he realizes he must send Amelia back to England so as not to ruin her, there was no pathos at all. He just stood upstage, waved his arms awkwardly and yelled out ugly high notes. His performance made you wonder what Amelia saw in him as a lover (in their duets he may as well have been singing to a lampshade, so dispassionate was singing) and his King came across as an absolute dolt. There were no discernible moments of fear for his life, or regret for his betrayal of his friend.

Kathleen Kim was expectedly annoying in the obnoxious role of king’s page Oscar. The low point might have been during “Saper vorreste” during which she danced around like an imp with wings. Wings, I might add, that I never understood why he/she was wearing. If Gustavus is like Icarus, why isn’t he the one wearing the wings? Kim’s clear, bell-like tone was more pleasurable than her completely un-boylike presentation.

Dolora Zajick was in fine vocal form as the soothsayer Ulrica with booming chest tones and a deliciously steely upper register, but Alden didn’t let her be much fun. Her Ulrica was perhaps the least fanciful character of the entire evening. She wore an unassuming black dress and white pearls, and stated in no uncertain terms and without histrionic gestures that she had spoken to Satan and that the King was going to be iced by his best friend. Interesting conceptually (perhaps Ulrica is supposed to be the one dose of hard reality in this fantasy land early 20th century Sweden), but not very effective theatrically.

Dmitri Hvorostovsky started cool and warmed up as his Anckarström became increasingly more homicidal. His is a tad too soft grained to be an archetypal Verdi baritone, but he has a liquid legato that he put to fine use during “Eri tu” in the last act of the opera and for which he was given a hearty ovation.

A golden tone she has not, but when she sinks her teeth into a phrase you can’t take your ears off of her. Her top gleams like the afternoon sun and she was dramatically compelling for the duration of her time onstage. She staggered hopelessly and sang passionately as she journeyed through the dark to find the herbs meant to rid her of her shameful love for the king.

My favorite moment of the evening was during a tender moment of the otherwise ecstatic love duet between Amelia and Gustavus in act two, wherein Amelia implores him to protect her from her own heart. Those beautifully colored pianissimo phrases are still sparking in my mind’s ear. The Met audience got this one right and the house came down when she came out for her bow.

Despite all of my qualms, I was never bored and (save for Alvarez) I was never disgusted. The production leaves much to be desired, but Radvanovsky, Zajick and Hvorostovsky manage to make this show worth seeing.

Photos: Ken Howard/Metropolitan Opera.

Comments