There was some disappointing singing, especially from three sopranos who blew break-out opportunities by presenting works-in-progress. (Hint – they were not in the Polish or the French opera.) The orchestra, drawn from here and there, served four different conductors with generally excellent results, although the sound from the vast pit can be both unblended and overpowering and the shape of the set seriously affects vocal projection. But the chorus! Under the direction of Susanne Sheston, the apprentice artists (joined by the Santa Fe Desert Choral for King Roger) delivered bold, sophisticated and vocally stunning performances.

The repertoire, from standard to obscure:

Stephen Barlow, who had conceived a fascinating film noir take on Carmen for Opera Theater of Saint Louis earlier in the summer, tackled Tosca for Santa Fe and left the performers, as he had in St Louis, abandoned. After the pleasure of conception comes the tedium of development, as any pregnant lady knows, but Barlow never gets out of bed. He couldn’t make his Tosca-has-the-hots-for-Scarpia notion work, in spite of an embrace and near kiss in Act One, along with some humping and a tumble on the floor in Act Two.

There’s more to directing than implementing a bunch of wacky ideas, and making the diva stab the police chief with her hairpin because a waiter, making a bizarre stage cross, picked up the knife she had dropped was a staging I actually had to check with the press office to confirm. Yes, it was a hairpin to the jugular. Who knew Tosca watched E.R.?

Yannis Thavoris’s period setting presented a spider’s view looking up into the cupola of Sant’Andrea della Valle, but required the entire cast—including the experienced Dale Travis, who stuffed the Sacristan with too many fussy bits—to walk on top of Cavaradossi’s painting.

Tenor Brian Jagde, Arabella’s Count Elemer, was a last-minute replacement as Cavaradossi, and we’ll see what Patricia Racette’s Tosca does to him in San Francisco in November. I enjoyed Jagde’s youthful physicality, and the playful exchanges of Act One (except for whacking Tosca with his paintbrush extender).

He’s got a beautiful golden sound, and managed “Recondita armonia” even with Frédéric Chaslin’s stodgy pacing, and kept a firm dynamic lid on “E lucevan le stelle.” Raymond Aceto sings Sparafucile, Banco, Ramfis, Timur and—you get it, he’s a bass. He gave a credible performance as Scarpia, but there was neither danger nor glamour in his dry, uniformly loud singing.

The most uneven performance came from Amanda Echalaz, who was making her U.S. debut and will be heard as Butterfly at the Met. Echalaz was a dramatically sure Tosca with an attractively dark voice, but needs more suppleness and better control of the top along with a lot more temperament. “Vissi d’arte” failed to impress even in its still, oratorio-style delivery, though other moments, especially “O dolci mani” along with the rest of the rooftop Act Three, packed plenty of vocal punch.

In the title role, Erin Wall also gave a hit-and-miss performance. She has the necessary velvety voice, spacious top notes, and graceful phrasing, and she saved enough for a beautifully poised and restrained stairway descent into the romantic final scene. But she captured Arabella’s pensive nature at the expense of gracious sociability, and I found her opaque demeanor charmless (perhaps it was my mistake to re-watch Lisa Della Casa’s lovely, luminous, expressive 1960 performance from Monaco Munich).

Mark Delavan, in exotic fur-lined coat, played the rich outsider Mandryka as a clumsy country bumpkin with the best intentions, an unexpected soul-mate to the restless proto-feminist Arabella. It’s a tricky role dramatically, because Arabella is pretty much the only person who finds Mandryka and all his talk about blood and hunting and bears attractive. With his capacious top notes and alert diction, Delavan handled the score’s endless chatter with ease, and declaimed “Mein sind die Wälder” (the description of his lands) with pride and “Ich habe eine Frau gehabt” (his backstory) with quiet intensity.

Albery placed Arabella and Mandryka side-by-side on a ballroom banquette for the intimate second act duet, and the singers complied with gentle, pianissimo tones, foreshadowing their luscious final duet “Und du wirst mein Gebieter sein.”

Heidi Stober’s Zdenka, the sister forced to dress as a man to save the family’s expenses, looked adorable in a schoolboy suit with wire-rim glasses, and her singing blossomed and shimmered most attractively. Stober met Zach Borichevsky’s eager, neurotic Matteo (his ringing voice marred by some squally high notes) with steady resolve and a perfectly poised, flawless performance.

Kiri Deonarine, in a bright red coat with riding whip, had an easy time with Fiakermilli’s riotous coloratura and high Ds. Sir Andrew Davis led capably and swiftly, though I missed the whooping French horns during the third act prelude. Maybe Matteo’s romp with “Arabella” was just a night of cuddling.

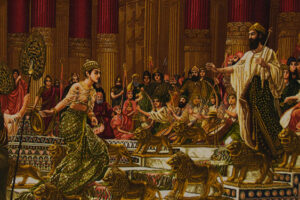

Bizet’s Pearl Fishers earned top prize for its excellent singing in a good-looking production that made dramatic sense (why is all that so hard to come by?). Last given at the Met in 1916, with Caruso and De Luca, here’s a work that needs more exposure. It’s got opulence and mystery and perfumey music with beautiful tunes (not just the famous duet), plus an action-packed plot featuring a love triangle involving a virgin priestess. And who doesn’t love shell necklaces and turbans?

Jean-Marc Puissant placed a picture frame in a wood-paneled drawing room around the exotic Ceylon temple setting, suggesting the work’s essentially European point-of-view. Lee Blakeley’s thoughtful staging set various community rituals against the love story, and he used the entire space with imagination and flair (torches and rainstorms and pageants, oh my!).

Brigitte Reiffenstuel’s costumes featured plenty of sweating, naked torsos (fishing is hard work, and Santa Fe has a reputation to uphold) and sun-bleached, layered folk garments. OK, so not all of the score is genial, but everything meshed attractively in this production (enhanced by Rick Fisher’s magical lighting) and moved swiftly to the fiery conclusion.

Emmanuel Villaume’s alert, expressive conducting drew stunning colors from the orchestra, and the languid atmosphere of the first act was especially mesmerizing. As Zurga, recently elected leader of the pearl fishing community, Christopher Magiera took a long time to warm up, and the duet “Au fond du temple saint” found him sounding tight and throaty. Magiera’s singing is elegant and smooth, though, and eventually the voice opened up considerably. Eric Cutler was superb as the outsider Nadir, Zurga’s rival in love.

From his first entrance (a visual homage to Indiana Jones), Cutler’s muscular tenor rang out handsomely and he was able to scale back for the introspective barcarole “Je crois entendre encore,” with full control of voix mixte and delicate diminuendos. Cutler’s was the finest male performance of the Santa Fe season.

And I’d give the female prize to Nicole Cabell. As Leila, the soprano looked sensational in various Eastern-styled garments and had the perfect voice: dusky and expressive, with pure, lovely top notes and plenty of variety in phrasing and color, with enough power to soar over the orchestra in several ensembles. Cabell’s physical poise and grace is another asset. The high priest Nourabad has plenty to do without the reward of a real aria, but bass Wayne Tigges has an imposing voice, and he’s worth keeping an eye on.

Photos: Ken Howard

Comments