L’incoronazione di Poppea nearly disappeared from the stage completely after its 1642 Venice premiere and a Naples revival in 1651. With the rediscovery of the score in 1888 and the scholarly attention that event brought, this superb example of the baroque opera thankfully returned to the stage and has been a repertory staple since the 1960’s.

Just two years before his death, Monteverdi created the first opera to use actual historical figures as characters rather than mythology (Nero’s rejection of the Empress Ottavia in favor of Poppea), set to a startlingly complex libretto by Giovanni Francesco Busenello.

Monteverdi’s melodious and varied music (most scholars believe he was assisted with this opera by Scarlati Sacrati and possibly Cavalli) culminates in its final act with Ottavia’s magnificently poignant Farewell to Rome and the final Nero-Poppea duet “Pur ti miro”, one of the most beautiful love duets ever written.

This opera puts forward a moral complexity that feels strikingly modern. The triumph of sensual love over virtue and reason exemplified by the triumph of the adulterous couple Nerone and Poppea shows how Monteverdi and Busenello found many shades of moral behavior in the very human characters presented. There are no “good guys” and “bad guys” in the piece, though there certainly is narcissism, lust for power, violence, and moral ambivalence. The opera weaves gods, emperors, philosophers, and comic servants in a seamless way. There is biting satire throughout, along with comic moments tinged with savagery.

David Alden’s strikingly modernist and visually stunning production from the Gran Teatre del Liceu of Barcelona is “regietheatre” at its best—there is strong and consistent point of view in the design and stage direction which illuminates the moral and psychological complexity of the characters and serves the music at the same time. I was particularly struck by Pat Collins’ lighting, bathing the stage in primary colors reflective of the emotional tone of each scene. There is also a wonderful use of light and shadow, almost a film noir quality.

A back wall and glassy floor reflect the lighting beautifully, and the “set” is very simple. There is no use of nature in the design—we have a chandelier when we’re inside, a streetlamp when we’re outside. A red sleeper couch is almost always in use, serving as seating for the gods all the way to a bed for the sleeping Praetorian soldiers.

Cupid sits atop a huge revolving door representing the struggles of the lovers—Poppea navigates it beautifully, but poor Ottone is completely unable to find a way in or out. Buki Shiff’s costumes range from elegant gowns to 70’s kitsch; the goddess Fortune is a self-absorbed “mean girl” all in white and constantly fixing her make-up, while poor Virtue is pregnant and on crutches.

Act I, Scene X is a splendid example of this directorial/design collaboration. Poppea, in a leather gown and a Medusa-like wig, literally climbs the walls as she tempts Nerone from a pink spotlight, suggesting a sensual dream. The effect is gorgeous.

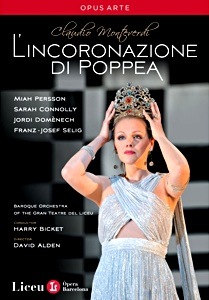

But what makes this production truly shine is the glorious singing in most of the major roles. Mezzo-soprano Sarah Connolly triumphs as Nerone, sumptuous of tone and creating a character on the edge of madness in his obsessive love for power and in his demanding his own will in all things. Connolly is capable both of ravishing, sensual vocal moments as well as the requisite bite for Nerone’s willful fury.

Beautiful Miah Persson is ideal as Poppea, singing with beauty, sensuality, and elegance. These two voices blend to perfection; every duet, especially the final love duet, is a lesson in glorious pairing. One can barely tell where one beautiful voice ends and the other begins.

The philosopher Seneca is sung with dark beauty by bass Franz-Josef Selig, and his tranquil, grounded character is in sharp contrast to the frenzy of the lovers. He serves here as the voice of reason, and even accepts death with equanimity. Alden makes one real misstep here—Seneca’s three acolytes are played as identical cartoon schoolboys, and somehow this takes away from the dignity and sadness of Seneca’s death scene.

Maite Beaumont is a real discovery for me as Ottavia. She has a plummy, rich sound and a charismatic presence in the role of the rejected Empress. There is an evenness of tone in everything she sings, and she is capable of much emotional nuance. Her Farewell to Rome is a model of expressive, stylish singing.

Special mention must be made for counter tenor Dominique Visse, who throws himself fully into the drag roles of Arnalta and Ottavia’s nurse. The man has exquisite comic timing, faultless phrasing, and buys into Alden’s ideas completely. His every appearance is a delight, yet he is not afraid to bring a razor’s edge to some of the dark and biting comedy here. I also much enjoyed Ruth Rosique’s plaintive Drusilla, looking like a refugee from How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying.

Only countertenor Jordi Domenech disappoints as Ottone—he is a decent comic actor, but the sound is grainy and cloudy, lacking in beauty and focus. I thought perhaps he had a cold, but after viewing excerpts of other performances, I found he sounded just as grainy there, too.

Well-known baroque conductor Harry Bicket manages to bring real dignity as well as many mood changes smoothly and with verve and grace as he leads this rich score. The Baroque Orchestra of the Gran Teater del Liceu plays charmingly, with much attention to detail and navigating the emotional changes in the music very well indeed.

This production of L’Incoronazione di Poppea did what very few operatic productions do for me—it haunted my dreams. Alden’s visions successfully highlight the emotional, moral, and intellectual questions asked by this great opera and manage to entertain in the process. The production is almost perfectly cast, splendidly sung, and unflaggingly fascinating.

Comments