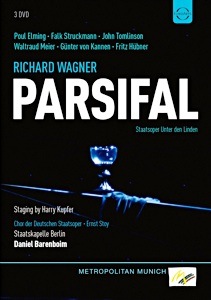

Certain opera productions become the stuff of legend as much for the circumstances surrounding the performance as for the musical results. Harry Kupfer’s 1992 Parsifal for the Berlin Staatsoper came at an epochal time, following the fall of the Berlin Wall and just after Daniel Barenboim was appointed the company’s music director. Putting an especially strong cast of under Kupfer’s direction was thought to portend a Renaissance for a house that had languished in the communist East, and hint at broader artistic possibilities for the reunified German republic.

Kupfer helped pioneer Regietheater at East Berlin’s smaller, more progressive Komische Oper and gained widespread notice with a Bayreuth Ring, also conducted by Barenboim, before this Parsifal rolled around. Working with designer and longtime collaborator Hans Schavernoch, he stripped away much of the opera’s religious and spiritual elements while putting an intense focus on the protagonists’ individual decisions and human emotions. The highly charged interplay was set in an oppressive metallic stage shell with a huge circular door suggestive of a space station or futuristic bank vault, and devoid of any of the natural beauties Wagner references in the text.

The effort, now available on DVD from EuroArts, has a somewhat dated, post-Star Wars sci-fi feel but admirably keeps most of the attention squarely focused on the singers. And though Kupfer’s direction won’t be to everyone’s liking – there’s as much writhing and crawling around as in a World Cup soccer match – the stage business does manage to keep the opera’s static plot moving at a respectable clip for four and a-half hours.

Kupfer places an especially strong focus on the characters of Amfortas and Kundry. The wounded ruler is wheeled about on a metallic chair or laying on a large wedge resembling a doorstop, the leader of a decrepit order of knights riveted on the Grail but largely impassive to expressions of faith and hope. Kundry, meanwhile, totally dominates the action during the opera’s pivotal second act — the only flesh-and-blood woman on stage owing to Kupfer’s decision to reduce the flower maidens to broadcast images on television sets scattered about the scene. The director also “spares” his heroine at the conclusion of the work, having her dreamily step forward with Gurnemanz and Parsifal as the curtain closes on the knights, suggesting she’s at last escaped the eternal cycle of death and rebirth.

All of this might come off as a persnickety rewiring of the composer’s intentions were it not for the total commitment of the cast, most of whom were accomplished Wagnerians in their vocal primes. Thirty-six-year-old Waltraud Meier is a force of nature as Kundry, chillingly recounting how she mocked Christ on the cross, then shifting from sultry to enraged as Parsifal rejects her advances during the latter half of the second act. The provocative performance, filled with nuance and elaborate blocking, offers an alternative to the Kundry that Meier essayed in the Met’s more traditional staging of the opera by Otto Schenk the same year that’s available on DG.

The hulking Poul Elming brings a pleasant lyric voice with baritonal qualities to the title role but at times appears boxed-in by Kupfer’s conception, expressing little more than confusion or anguish to all the goings on. John Tomlinson is an authoritative, satisfyingly resonant Gurnemanz, whose excellent diction and savvy use of small gestures draw the listener into his long monologues. Falk Struckmann brings strong dramatic sensibilities to Amfortas, palpably expressing pain and hopelessness in the presence of the Grail, though his voice is arguably the least interesting of the four principals. Günter von Kannen and Fritz Hübner are also effective in the roles of Klingsor and Titurel.

Barenboim, filmed from the back of the orchestra for extended stretches, looks a little like he’s being held at gunpoint but leads a spacious, wonderfully detailed account of the score that’s supportive of the singers yet sensitive to the architecture of the long acts. Though the interpretation isn’t as flashy as Christian Thielemann’s or as lush as James Levine’s, there’s a majestic, slightly foursquare quality to his reading that makes this one of the best modern takes available on DVD. The Staatskapelle orchestra and chorus are wonderfully responsive, projecting a real sense of occasion.

Having all these well-traveled and accomplished artists in one place during their best years is probably justification enough to add this Parsifal to one’s collection. Listeners who’ve experienced other revisionist takes on this elusive work in the two decades since can also reassess how well Kupfer realized the opera’s mysterious qualities and paradoxes, and if he discarded too many elements to realize his vision.

Comments