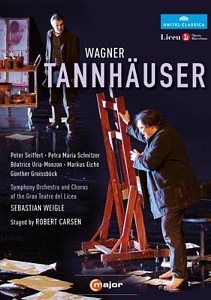

Certain contemporary opera directors have taken to portraying Wagner protagonists as visual artists to better illuminate the characters’ moral and aesthetic struggles. The composer’s great-grandaughter, Katharina, transformed Walther von Stolzing into a kind of graffitist for her controversial 2010 Die Meistersinger at Bayreuth. Before that, Canadian director Robert Carsen reconceived Tannhäuser as an outcast painter in a provocative but uneven 2008 production at Barcelona’s Liceu that’s now available on DVD

from Unitel.

Tannhäuser’s medieval notions of sacred and profane love and its message of salvation might, indeed, make the opera’s plot ripe for some dramatic tweaks. Wagner himself was drawn to the tale through a cynical, early 19th-century reworking of legend by Heinrich Heine, and was adamant the plot’s religious references were more poetic imagery than evidence of a particularly Christian drift.

Such admissions seem to have encouraged Carsen to rework the plot as a story about modern-day artistic validation. Tannhäuser’s sin of shunning the chaste Elisabeth for the pagan goddess Venus, and the journey to redemption that follows, recedes in a revisionist story line that delivers the character’s spiritual fulfillment in the form public acclaim for his daring canvases.

The opening scene utilizes the Paris version of the opera and sets Tannhäuser’s studio in the Venusberg, with the naked goddess posing on a mattress. The artist’s bold brush strokes are pantomimed by a crowd of increasingly frenzied dancers, who are so taken with Venus that they orgiastically cover themselves in paint before collapsing exhausted.

The Act 2 song contest is portrayed as a painting competition in the tony gallery of the Landgrave Hermann, during which each of the artist’s songs introduces the unveiling of another canvas. Principals and chorus enter the tableau through the auditorium (Elisabeth sings “Dich teure Halle’’ from the edge of the orchestra pit), and Carsen’s accomplishment here is giving everyone enough to do to make even supernumeraries’ characters pop out in three dimensions.

The most daring, and questionable, interpretive liberty comes in Act 3, which essentially strips out the pivotal confrontation between morality and sin. Instead, Elisabeth slips into a sort of daydream during which she takes on the dress and other characteristics of Venus. Both women wind up posing for Tannhäuser, who, urged on by Wolfram, whips up a work that wins acclaim from the establishment and is accepted into a gallery of once-shunned masterpieces. Where exactly this all leaves the chorus of pilgrims returning from Rome is anyone’s guess.

Clever lighting and spare sets play with the audience’s notions of space throughout the action, though the effect captured on the DVD probably reflects only a fraction in-theater experience. I would have loved to have been present for the sardonic yet oddly pitch-perfect art gallery scene, with its champagne-swilling, hors d’oeuvre nibbling denizens.

In the title role, the esteemed German tenor Peter Seiffert brings great musicality and feeling to moments like Tannhauser’s Act 3 Rome narrative, only taxed in the upper register, where his vibrato becomes distracting. His real-life wife, Petra Maria Schnitzer, spins some lovely lyrical lines but can’t hide the effort needed to reach Elisabeth’s top notes, which sound a bit shrill.

Baritone Markus Eiche, filling in for the originally scheduled Bo Skovhus as Wolfram, has a small but pleasingly polished voice and elegant delivery that makes the great solo “O du, mein holder Abenstern” sound a bit like a lied. Austrian bass Gunther Groissbock is a fine, upward-striving Hermann in Carsen’s conception, while French mezzo Beatrice Uria-Monzon is suitably alluring as Venus, though, like some of her castmates, struggles with her role’s high tessitura.

Conductor Sebastian Wiegle leads a technically sound account that captures the opera’s melodic ebb and flow without making a particularly strong interpretive impression. The Prelude and Venusberg music is especially uninspired. The Liceu chorus acts fabulous and sings with vigor but still falters with some sloppy rhythms and inadequate pit-stage coordination in the final two acts.

Not surprisingly, Carsen makes a better case than most for an interventionist rethinking of this work. His paean to progressive art appropriately syncs in spirit with Wagner’s own efforts to test the boundaries of musical convention. But the concept will likely test the patience of anyone who views Tannhauser as, first and foremost, a moral lesson and who has little use for external allegories to illuminate the work’s basic tensions.

Comments