The dreams of the Enlightenment may be lovely, but the social mores of their dreamers have not aged gracefully. Despite a message of fraternity, the poor handling of racial tensions, blatant celebration of gender inequality, and an idealized benevolent dictator sit poorly today.

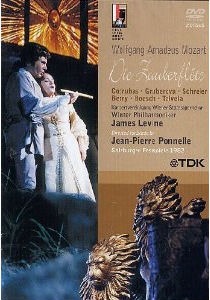

In his staging for the Salzburg Festival, Jean-Pierre Ponnelle eschews politics and creates a visually charming production, a choice that often brings us wonderful images but also unwittingly highlights the problems it ignores. This 1982 recording is also marred by poor audio engineering, which picks up the orchestra clearly, but muffles and distorts the singers, particularly the women. The audience, starchily Teutonic, are ruthlessly quiet and polite.

But despite these shortcomings, this is the Salzburg Festival, and even for a revival (the original production opened in 1978), the quality is remarkably high. Peter Schreier sings Tamino with a deft touch. His voice isn’t particularly youthful, but it has a heroic ring that doesn’t sacrifice flexibility.

As Pamina, Ileana Cotrubas is lovely, but the sonics do her no favors. I don’t find her stylistically perfect –her phrases tend to drop off untidily, and she lacks a golden tone – but these same ‘faults’ make her sound like a teenage girl, at turns rebellious and acquiescent. Pamina is rendered so completely passive by the libretto, essentially passing from the hands of one man (her kidnapper) to another (a man who falls in love with a picture of her), that a touch of humanity makes her interesting to watch.

Edita Gruberova is a justly famous Queen of the Night. Again, bad sonics derail the focus on sustained notes, but even so, the coloratura has pinpoint accuracy. Her arias are the most famous of the opera, but this is one of the few productions I’ve seen where she doesn’t steal the show.

Instead that honor goes to Christian Boesch as Papageno. This part would launch him into appearances at major international opera houses, and rightly so. He shows an incredible patience, gamely playing comic bits for the audience, and gradually winning some chuckles (he is quite funny, and the polite silence from the audience is aggravating). He uses his sweet baritone cleverly, bringing something new to the character with each stanza.

The remaining cast is good, if less interesting. Martti Talvela is a stoic Sarastro, who sings beautifully in the first act, but only approximates the low notes of the second half. The three ladies (Edda Moser, Ann Murray, and Ingrid Mayr) make an effective albeit safe trio; the production downplays their sexiness and spunk, and as a result they have little to play with. The chorus is exemplary, although they are also relegated to the background.

Predictably, Monostatos is the blindingly sore spot. Horst Hiestermann’s singing is not the issue; his voice is light, and he moves through the brief aria easily. Monostatos and his chorus of lackeys appear in dark black face, and the result is distinctly uncomfortable – probably the reason this DVD hasn’t been issued sooner. To be sure, the part is already racially problematic: the libretto may assert that he is not a villain because he is black (then why choose to make him the only black character?), but the entire thing fits too neatly into stereotypes.

Racial impersonation has a long history and very continued presence in opera – while most new staging of Zauberflöte find alternatives for getting out the shoe polish for Monostatos, the rules are different for Otello or Cio-Cio San. Obviously, every production is a product of a specific time and place, and today I think Ponnelle would have made some different choices. Mozart’s works have been contentious throughout history, with productions from various time periods sanitizing offending bits. Scholarship exists both condemning and defending Zauberflöte, and some stage directors simply choose to ignore the issue by changing the markers of difference (for example, Monostatos as Shrek).

But ultimately, I don’t know quite know where this specific choice leaves the experience for me. The production is comfort food, and this unwelcome ingredient throws the entire balance off, leaving a bitter aftertaste. It’s the tip of an iceberg, throwing other issues I usually manage to ignore into a harsh light: the current Taymor production at the Met, which takes out the racial problems without coming to a satisfying solution to the gender disparity, irks me slightly but doesn’t derail the opera for me.

To be fair, I don’t think sanitization is the best solution, and I admire directors like Kentridge who question the veracity of the libretto in their presentation, but at the same time I have to acknowledge that this is one of the most pleasantly escapist works in the repertoire.

Ignoring this uncomfortable choice and the shortcomings of the libretto, Ponnelle’s direction is masterful. His balance of music and movement is unique, and his vision is harmonious. The cast knows it, and they look supremely at ease. This may feel like a ‘traditional’ production, but if Ponnelle is not radically modern, he is always gently undermining the lovely images he conjures up.

The set is a particularly efficient use of the Felsenreitschule, with set pieces rising and falling into mossy ruins. This includes a miniature stage with a medieval tapestry depicting the Felsenreitschule – a broad wink rather than a ponderous ‘play-within-a-play.’ One telling moment has Papageno catching birds that hang from wires; he takes out a large scissors and cuts the strings, nimbly catching them in his basket. There is always a sense of questioning, a visual world that acknowledges its own illusion. Maybe this is a suggestion to take the outmoded ideals of the libretto less seriously, to simply enjoy the constructed dream.

But no matter how the production comes across, Mozart is the main event, and the real treat of the evening is James Levine at the podium. From the opening notes, he coaxes great walls of sound from the orchestra, nimbly manipulating colossal structures that I’ve never heard in this score before.

This is a grandly conceived performance, and if the Masonic ideals in the libretto are less than convincing, this is truly uniting music. Incidentally, Levine also receives the loudest laughs of the night when he gamely participates in a charming interplay with Papageno – the smirk on his face is priceless. This recording is a testament to both his abilities as a musician, and as a collaborator.

In many ways, seeing this production today reaffirms the need to develop and change operatic practice as our cultural ideology changes. Directors today are more aware of these issues, and productions tend to be either more sanitized, or more politically aware.

But for those wishing to see this classic Zauberflöte, there is an alternative: Boesch and Ponelle developed a version of the same production for children that also survives as a DVD, with mostly the same cast. If you want to see a fairytale, I’d recommend the one for children, devoid of the ugliness we accumulate as adults.

Comments