The relative obscurity of Karol Szymanowski‘s Krol Roger (King Roger, 1924) can only be blamed on its being in Polish. The music is often as thrilling as anything by Janácek or Bartók, and the libretto by Jaroslow Iwaszkiewicz (heavily adapted by the composer) is as full of provocative philosophical ideas as operas by those composers or even Wagner.

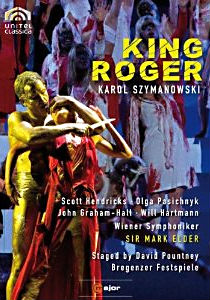

A further complication may be that, at about 90 minutes, its three acts work best performed continuously, as they are in the new DVD from the Bregenzer Festspiele, directed by David Pountney.

Like Elektra, Bluebeard’s Castle, or From the House of the Dead, it’s a bit short for a full evening, but hard to place on a double bill. Lacking a “name” composer, however, King Roger has perhaps been seen as a tricky proposition, and received its North American stage debut only in 2008 at that haven for musical obscurity, the Bard SummerScape Festival.

In fact it would make a fine curtain-raiser for Bluebeard’s Castle. Like Bartók’s one-acter, King Roger shapes a legendary story into a highly schematic opera of ideas in which an horrific ending reads more as an inevitable intellectual Q.E.D. than as a human tragedy. Like Bartók, Szymanowski provides more than enough moments of musical excitement to keep the chess pieces moving.

The ostensible leaping-off point for King Roger is a retelling of Euripides’s Bacchae, transported to medieval Sicily, and cast as a collision between Christianity (portrayed as a Western-Byzantine hybrid) and a charismatic paganism that eventually reveals itself (as in Euripides) as a Dionysian cult. But there’s more: the titular king, whose historical namesake did in fact cultivate an unusually cosmopolitan court in the early twelfth century, is not so much a tragic hero caught between two competing religions, but is rather a Nietzschean super-man whose gradual enlightenment allows him to transcend orthodoxy by embracing a sensualized will to power.

This enlightenment unfolds over three acts that Szymanowski (directing his librettist) set in locales that migrate culturally from West to East: Christian church, Roman palace, and Greek ruin. Though clearly distinguished in Szymanowski’s music, these settings here blur together on the minimal but gorgeous amphitheater-like unit set, tricked out with moving steps, hidden trapdoors, and striking abstract lighting projections.

Not much is lost by this, since the action is pretty straightforward across the three acts: a strange Shepherd from foreign parts (tenor Will Hartmann, painted gold) preaches a new kind of religion based in nature, love, and sensual abandon. King Roger (baritone Scott Hendricks) first takes the side of religious orthodoxy, represented by the black-clad chorus, but his fascination with the Shepherd is encouraged by his counselor Edrisi (a wobbly John Graham-Hall) and most of all by his wife Roxana (Olga Pasichnyk, bald), who from her first appearance is in thrall to the foreigner. Eventually the chorus succumbs also, and finally Roger himself.

The final moments of the opera are somewhat ambiguous, however: the rest of the throng (according to the libretto) run off with the Shepherd, now recognized as Dionysus, while Roger (and, as always, Edrisi) are left to greet the dawn of a new day. Roger’s enlightenment is emphasized in the end, rather than his devotion to the new god.

Mark Elder leads the Wiener Symphoniker in a detailed yet atmospheric reading of the score, enhanced by forceful choral singing from two Polish choirs and a local boys’ choir. The choral contribution is vital to this opera, most obviously in the absolutely stunning and unprecedented a cappella hymn (stylistically suspended between Rachmaninov and Tavener) that opens the work, so the expense of importing native-speaking choruses was well worth it.

The three principals, on the other hand, are American, British, and Ukrainian, but the language seemed to hold no terrors for them. As Roxana, Pasichnyk has the most dramatic lines, particularly in her Act II aria and several climactic scenes in which she carried well over thick choral and orchestral textures. Hartmann’s Shepherd was also powerful, but I missed the final measure of seductive expressivity in his climactic moments.

Checking the score after hearing the opera I was surprised to see that this role lies lower than I would have thought. The role of King Roger is somewhat less lyrical than the other principals, consisting largely of frustrated prevarication, but Hendricks conveyed the character’s anguish and enlightenment with a focused, expressive sound.

If his characterization lacked subtlety, however, it may be because Pountney’s vision of the work allowed for little. Though the musical expression of enlightenment is conveyed in intensely sensual ways in this opera, it remains fundamentally spiritual, as Pountney seems not to have realized.

The Shepherd’s appeal is instead seen as primarily physical (and often simply sexual), with the climactic choral scenes in Acts II and III reduced essentially to orgies in the style of Samson et Dalila. The resulting frisson was sometimes effective, particularly when it cast Roger’s dawning self-awareness as a kind of coming out, but it leads to far too much writhing about and open-mouthed gaping as characters traverse an oversimplified spiritual journey.

This production neatly resolves the ambiguity of the final scene in a way which sets the opera’s depiction of a religious cult in a meaningful light. Instead of merely departing for parts unknown, at the height of the final frenzied dance all the human characters quite suddenly do what religious cults often do and slit their wrists, as the shepherd cuts Roxana’s throat.

As they sink to the front of the stage, dying, Roger is revealed not to have taken this final step, and his gesture towards the sunrise symbolizes his escape from the cult as much as the attainment of a new spiritual state. This interpretation is certainly available in the opera as written, but Pountney’s direction gives this scene a strongly grounded dramatic sense that seems lacking in earlier scenes.

Simon Rattle‘s recording of the opera on EMI (with Thomas Hampson in the title role) will remain a top audio choice for many, but with a strong cast and orchestra, stunning visuals, and a clear and valid (if sometimes misapplied) directorial vision, the Bregenz King Roger is a worthy first appearance of this vital opera on DVD. Now if only we could see in on more American stages.

Comments