Great expectations awaited the Met Opera’s new production of Das Rheingold, staged by the ambitious Canadian director Robert Lepage, and rightly so. With a 45-ton set carrying a $16 million price tag, a world-renowned cast, and maestro James Levine celebrating his 40th anniversary on the podium, who wouldn’t be on the edge of his seat as the lights dimmed and the chandeliers rose? And the verdict after 2 1/2 intermissionless hours of Wagner: It seems that James Cameron has invaded the Metropolitan Opera House, for not since the advent of the film director’s 2009 sci-fi opus Avatar has anything simultaneously so splendid and silly been seen by a New York audience.

Like a big, expensive Hollywood extravaganza, Lepage’s production relies on state of the art technology to create some stunning visuals. The main characteristic of the much-publicized set are 24 gigantic beams that twist and turn on a central axis to provide the setting for each scene. Some are breathtaking, particularly the resplendent opening image of the mermaid-like Rheinmaidens floating upward from the sea and emerging on a pebble beach, or a striking sequence in which Wotan and Loge descend into the Nibelheim that defies the laws of physics. Pristine video projections and other impressive lighting effects add to the richness of the atmosphere.

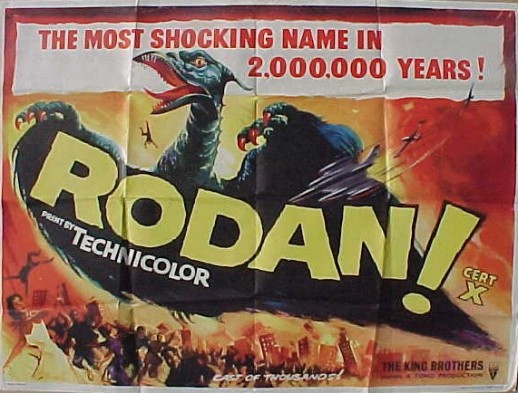

But despite the modern mechanical conception that defines this staging, much of the production remains pat, and, at times, embarrassingly simplistic in its literal-minded interpretation of the text. The biggest missteps in this regard include the costumes, which look plucked from an oversized children’s fairytale book, Freia splayed out at the bottom of a net covered in a heap of gold-painted plastic armor, and Alberich’s transformation into a giant, rubbery serpent, which puts one in mind of effects used in the 1956 Japanese cult horror film Rodan.

The singing is not particularly remarkable either. Bryn Terfel is terribly miscast as Wotan, never rousing a commanding enough vocal or physical presence for the king of the gods. Stephanie Blythe, a notably rich vocalist, provided a vocally decent but colorless interpretation of Fricka. The biggest ovation for a cast member deservedly went to Eric Owens, who delivered an energetic and heartfelt performance as Alberich and expertly tracked the character’s journey from wounded outcast to power-obsessed tyrant.

But the true king of the night was Levine, who despite his health problems over the last year guided the orchestra with spirit and determination. Greeted by a warm ovation both pre- and post-performance, he remains, both in stature and in practice, the untouchable element of the production. Lepage, on the other hand, was received at curtain call with a characteristic opening-night smattering of cheers and jeers. You may sympathize with both.

Comments