The Berlin Philharmonic brought a spooky Halloween treat to New York on Thursday night, just a few days late. They are at Carnegie Hall for a three-night residency, offering the complete Brahms symphonies along with selected earlier works by that ugly duckling of Brahms disciples, Arnold Schoenberg. They are also far from home during Berlin’s anniversary celebrations of the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, having taken a prominent role in the celebration twenty years ago. And it was an American – one Leonard Bernstein – who conducted Beethoven’s Ninth at the Wall, famously supplanting the word Freiheit for the word Freude in its finale. For most of last night, it would seem these remembrances were far from their minds.

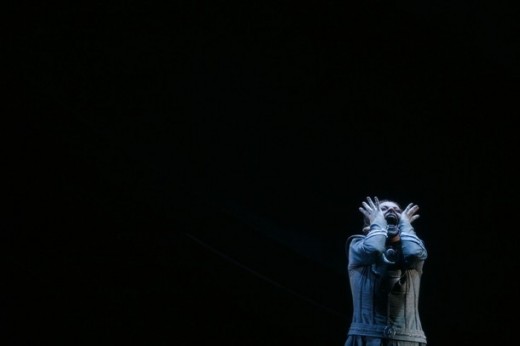

When the pretty, slender Evelyn Herlitzius entered the stage to sing Schoenberg’s 1909 atonal monodrama Erwartung wearing a long, blood-red roll-necked gown, she was already fully in character – a curiously icy and zombie-like stare perfect for Pierrot Lunaire. But she sang a work more akin to Salome than Pierrot, a full-voiced, lyrical account of Schoenberg’s expressionist scena tempered by a somewhat steely, cold tone.

In very good voice, she artfully careened over the perilous cliffs of orchestral crescendo, occasionally shrieking (there is no other way) through Schoenberg’s manic stream of consciousness, and exhibiting considerable vocal might where it mattered. This was not a sensual, dreamy account of Erwartung, but rather a terrifying, waking nightmare.

Choosing to swallow some consonants or reshape a vowel in service to the melodic line, Herlitzius didn’t fall into the pseudo-Sprechstimme trappings of many Erwartung executants, opting for a precise, yet fully sung, account of Schoenberg’s vocal tone-poem. As she observed the body of her beloved lying in the mulch, she leaned on the words “Er liegt da!,” stressing the long vowel but without any hint of vibrato or color. No breathy faking here, she delivered even staccato “Ah!” exclamations with a supple roundness and firm tone. Though she clearly worked for the big notes, her sound was not forced, and in the end she prevailed against a formidable Berlin orchestral torrent. She won a similar torrent of adulation from the audience, and it is safe to expect that we will see more of her.

Perhaps the orchestra shone brightest of all in the evening’s “overture” (of a perverse sort), Schoenberg’s Chamber Symphony No. 1. Originally scored for 15 solo instruments, the composer’s full orchestral version presented here bears a whole catalog of challenging ensemble problems. Solo strings link up with tutti strings in freakish triplet figurations, complicated woodwind entrances overlap with daunting brass countersubjects, all amid a puzzle of dynamic shadings. This huge orchestra tossed it off as if it were chamber music, in a breathtaking display of orchestral virtuosity and surgical precision.

The Brahms Second Symphony started out weirdly Brucknerian. Rattle took a lackadaisical approach to the more expansive bars, then churned out huge crescendos in the more rhythmic passages, but avoided climax or catharsis. He tends toward under-conducting, showing few beats, instead drawing shapes or posing in the air while several whole bars of music pass by. Though they should be used to him by now (he has been music director since 2002) it seemed to confuse the players, who occasionally dropped notes and played in rests. Rattle and the Berlin orchestra have been the topic of some gossip suggesting they do not always see eye-to-eye, especially in the German romantic repertoire. This was the evidence.

By the finale, however, it no longer mattered – the obvious joy with which this orchestra plays this music was irrepressible. After soaring through the hopeful second subject’s recapitulation, and landing on the tutti chords that announce the end, they seemed to want to pull back the tempo, to stay in the moment, before diving into the coda with smiles on their faces. A recognizable sound and feeling filled Carnegie Hall – a golden-hued tenor of pride and nostalgia – and if you closed your eyes, it could have been that same Berlin Philharmonic of 1963, or 1978, or November of 1989: Unvanquished.

Comments